Introduction

In 2015 Eastville Workhouse Memorial Group (EWMG) released the death records of more than 4,000 inmates of Eastville Workhouse. These were paupers who were buried over the period 1851-1895 in a piece of waste ground adjacent to the institution at 100 Fishponds Road, Eastville, known today as Rosemary Green. The massive public response to the release information about these ‘lost Bristolians’ spurred EWMG and the local community of East Park estate to raise money for two memorials and a plaque, to mark their resting place and the location of Eastville Workhouse (demolished in 1972). It also encouraged a small team of researchers from EWMG to consider what happened to pauper bodies after Rosemary Green became ‘full’ in 1895. Subsequent research demonstrated that the Guardians of the Barton Regis Poor Law Union who managed Eastville Workhouse decided to begin interring bodies of unclaimed paupers in nearby private and public cemeteries.

It is almost four years since we exposed this new chapter of hidden history in the article ‘New pauper burial research at Greenbank cemetery’, and since then we have expanded our studies of the workhouse death registers to cover the period from November 1895 to the eve of World War one in July 1914. This article outlines our findings amongst the records of 4,743 people who died over this period, the vast majority of whom were inmates of Eastville Workhouse. The full dataset with explanatory notes can be downloaded here. This article also utilises the research of John Butland Watts and his colleagues at the Bristol and Avon Family History Society (BAFHS) and the Friends of Ridgeway Park Cemetery (FRPC) into the burials at Ridgeway Park and Greenbank cemeteries.

From consecrated waste ground to private cemetery

It is unclear why the Guardians of Eastville Workhouse decided to cease burying unclaimed pauper bodies in Rosemary Green in the autumn of 1895. It is most likely that cost was the driver. Our research into the finances of the workhouse, which was published in ‘100 Fishponds Road – Life and death in a Victorian Workhouse’, demonstrated that reducing costs of the institution to ratepayers was the primary aim of the majority of Guardians, rather than caring for the sick, the mentally ill, children, pregnant mothers, the infirm or the elderly. This was a reoccurring theme over decades and also applied to the costs incurred after a pauper died in the institution, weather a baby, infant, child, adult or geriatric.

The use of the waste ground (now Rosemary Green) next to the institution although controversial and costly to consecrate, had over 40 years, saved a huge amount of money.[ 1 ] This included the cost of coffins, transport, and interment, in returning bodies to their home parishes within the Poor Law Union (PLU). There may have been other reasons for the change in policy, obviously space was an issue but there was still room for a potential extension of the burial ground. [ 2 ] The overcrowding in Rosemary Green had certainly led to burial practices such as ‘packing and stacking’ of bodies which may have come under scrutiny. As we shall see, such dubious burial practices were not solely the province of penny-pinching Poor Law Unions.

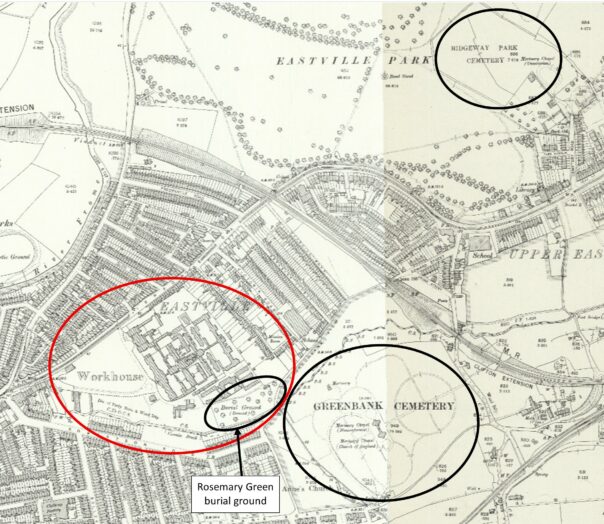

The Guardians of Eastville Workhouse chose three cemeteries to fulfil their need for burial space for unclaimed pauper bodies over the twenty years after the closure of Rosemary Green in 1895. The two primary locations were Ridgeway Park and Greenbank cemetery (see Figure 1[ 3 ]). The former located a few minutes’ walk away at the top end of Eastville Park, was opened in 1888 by a private company which was wound up in 1949, with the cemetery coming into public ownership in 1954.[ 4 ] Greenbank cemetery, which lies adjacent to Rosemary Green, was opened in 1871, and in 1895 became the first private cemetery to be taken over by the Bristol Corporation.[ 5 ]

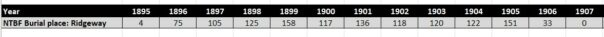

The summary for the dataset demonstrates that for unclaimed pauper bodies, i.e. those ‘not taken by friends’, (NTBF) the Guardians used Ridgeway Park cemetery from November 1895 to March 1906, interring a total of 1,264 corpses (see Table 1).

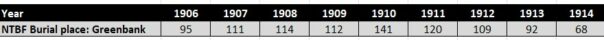

From March 1906 the Guardians switched to using Greenbank cemetery for the burials, interring another 962 bodies until the eve of the First World War in July 1914, the point of cessation of the death registers (see Table 2).

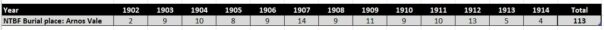

In addition to these two principal sites, according to the notes in the death registers, a total of 113 unclaimed pauper bodies, mainly those of the Roman Catholic faith and many of whom were of Irish descent, were interred in Arnos Vale cemetery in south Bristol from 1902 to 1914 (see Table 3).[ 6 ]. This private cemetery was opened in 1839 and taken into public ownership in 2003.[ 7 ]

Over the ten-year period from 1895 to 1904, only four unclaimed pauper bodies were given to the medical school for dissection. This should be compared with the period of maximum pressure to reduce PLU costs by the anti-welfare ‘crusaders’, the ten years from 1872 to 1881 which led to 69 paupers being given (sold) to the Medical School.[ 8 ]. The practice seems to have halted in 1904.

The question remains, why did the Guardians of the Eastville Workhouse (Barton Regis PLU) choose to move from interring unclaimed pauper bodies in Rosemary Green to Ridgeway Park cemetery, rather than Greenbank or other available burial grounds? If it was merely a question of convenience, then Greenbank would have been the best choice as it was directly adjacent to Rosemary Green which itself was next to the hospital buildings in Eastville Workhouse (see Figure 1).

A clue lies in a debate amongst the Bristol Board of Guardians (Bristol PLU) in 1896 about burials at the Stapleton Workhouse. These were becoming problematic in a similar manner to Rosemary Green at Eastville the previous year because:

The whole of the ground had already been buried in, some parts more than once. Further, it was not properly drained, and its close proximity to the [Stapleton] Workhouse was a disadvantage.[ 9 ].

Indeed, this had become painfully obvious eight years previously in 1878 when a Guardian recalled that he had seen ‘coffins actually floating about’ after flooding.[ 10 ]

The Bristol Guardians had the land they owned around the Stapleton Workhouse surveyed, but it was found to be unsuitable for burials, so they enquired into buying some land in the locality. This was also a failure, so finally, they considered the new nearby cemeteries of Ridgeway Park and Greenbank around a mile away from Stapleton workhouse. The guardians discovered the cost at Ridgeway Park cemetery for the most basic burial was 6s, compared to Greenbank at 19s 6d, more than three times as much. The Ridgeway Park Cemetery Company (RPCC) also offered a two-year deal to the Bristol Guardians, guaranteeing their prices would be fixed for that period.[ 11 ]. It seems very likely that when the Barton Regis Board of Guardians were faced with similar issues at Eastville Workhouse the previous year, they would have taken a similar cost-driven decision.

‘By friends’: Claimed and unclaimed bodies

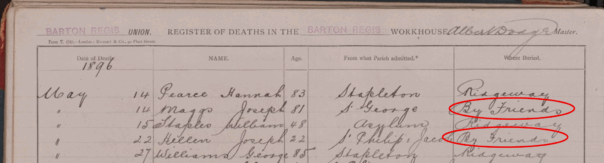

A cursory inspection of the ‘Where Buried’ column in the Eastville Workhouse death registers shows the expression ‘Taken by Friends’ or ‘By Friends’ is very common (see Figure 2).[ 12 ] This refers to bodies that were recovered from the workhouse by family and friends who could afford, and prove they could pay for, the costs of burial. The remainder of the unclaimed bodies became the responsibility of the PLU and were buried in either Ridgeway Park, Greenbank or Arnos Vale cemeteries or sold to the Medical School. It is important to note that ‘unclaimed’ does not necessarily mean that no one came to the workhouse to claim the corpse or that the deceased had no friends and family.

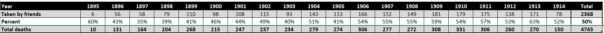

In our studies into Eastville Workhouse in the Victorian period we noted the ratio of those bodies successfully claimed by friends and relatives from the PLU. This ranged from 20 (1 in 5) to 25 (1 in 4) percent over the years 1851-1895.[ 13 ] In contrast in this study these ratios have significantly changed. Table 4 gives the percentages of bodies claimed by friends and relatives over the period of study.

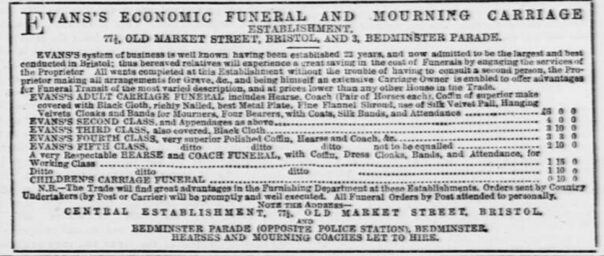

It is clear that prior to 1906 (barring the small sample in 1895), the ratio increases from about 40 to 50 percent and after 1906 the ratio never drops below 50 percent (1 in 2). This may reflect a number of factors, including better wages and more disposable income amongst the working class and the prevalence of ‘friendly societies’ or their ilk which encouraged the working class to save for ‘respectable funerals’.[ 14 ]

For bodies that were taken ‘By Friends’, many were buried in Ridgeway Park or Greenbank for convenience because these cemeteries were close to the workhouse where the bodies were stored. The burials of ‘claimed’ corpses from the workhouse that occurred in Greenbank cemetery have been cross-referenced with the published transcription of the cemetery data.[ 15 ] This gives extra information about the date of interment, and the burial number. Similar information can be obtained by comparing the burials of bodies ‘taken by friends’ with cemetery data from Ridgeway Park. [ 16 ]

Burial practices from Rosemary Green to Ridgeway Park – out of the frying pan and into the fire?

One might expect that the decision to move from burying unclaimed pauper bodies, inmates from a workhouse, in a piece of (albeit consecrated) waste ground owned by a Poor Law Union in the Victorian period to a recently opened private cemetery in the Edwardian period would have improved standards of burial practice. Sadly, the evidence suggests the contrary.

Rosemary Green

On a daily basis the burials at Rosemary Green from 1851-1895 were managed by the master of the workhouse and he was directed by his superiors, the board of guardians of the Poor Law Union. Our previous investigations into these practices showed that there was evidence of systematic ‘packing’ and ‘stacking’. The former refers to squeezing as many burial plots into a given space as possible. At Rosemary Green the Guardians even ordered that bodies should be buried under the footpaths used to access the site by the inmate gravediggers, rather than incur the cost of a further consecration of land.[ 17 ]. The latter term involves burying multiple bodies on top of each other. However, this was not normally achieved in one interment but required returning to earlier graves (or ‘old ground’ as it is referred to in the workhouse death registers), digging them up and burying more people vertically in the same plot. [ 18 ]. This effectively led to repeated desecration of existing graves. There was evidence of the practice of ‘stacking’ at Rosemary Green both in the death registers and from an eyewitness account of the foreman tasked with mass disinterment when the workhouse was demolished in 1972 [ 19 ].

The public health and burial acts of the 1840s and 1850s, influenced in particular by cholera epidemics, began to systematise burial practices and gave authorities power to close graveyards and burial grounds if they were ‘considered dangerous to health’.[ 20 ]. This could include situations of extreme ‘packing and stacking’ in inappropriate locations. However, there was a problem, not with the aim of the burial laws, but their enforcement. This involved the need for regular inspections and generalised compliance by institutions such as workhouses, private cemetery owners and corporations (local councils) that ran municipal cemeteries. The lack of clarity about specific burial practices in the burial acts and a lack of enforcement allowed Poor Law Union guardians, cemetery owners and officers of corporations to engage in practices such as ‘packing and stacking’ without fear of discovery and thus sanction. [ 21 ].

Ridgeway Park

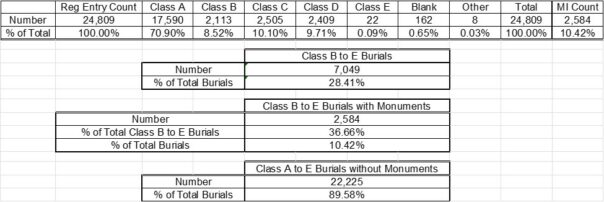

The private cemetery at Ridgeway Park was owned by a joint stock company. The leading shareholder was Thomas Wood who had originally owned Ridgeway House and its grounds and had sold the latter to the company to be used for the cemetery.[ 22 ] The Ridgeway Park Cemetery Company (RPCC), as it was incorporated, had a sliding scale of charges for interments ranging from Class A to Class E.

Class A burial plots were the cheapest and were designated as ‘common graves’. In 1919, Class A interments cost 12s for an adult (£132 relative to average wages), 9s for child under 10 years of age and 3s for a baby less than a month-old.[ 23 ] Class B and C were designated ‘Freehold’ plots with locations for the former selected by RPCC and costing £2-8s (equivalent to £527) for those above 10 years of age. The ability to choose a plot’s location pushed the price of Class C up to £3-10s (£768). Plots classed as D and E were clearly more exclusive, both allowing friends of the deceased to choose a location and the latter being described as ‘walled graves’.[ 24 ]These ranged in price from £4-4s (£1,405) to £10-10s (£3,513). It should be noted that these prices are for a 75-year lease on the burial plot only. They neither included the cost of grave stones, plinths, tombs and or building materials, nor the minister’s fees or other funeral payments. ‘Right of interment’, that is for the customer to place another body in the same location (a relative perhaps) extended to categories B-E and these were offered at about half-price.[ 25 ]

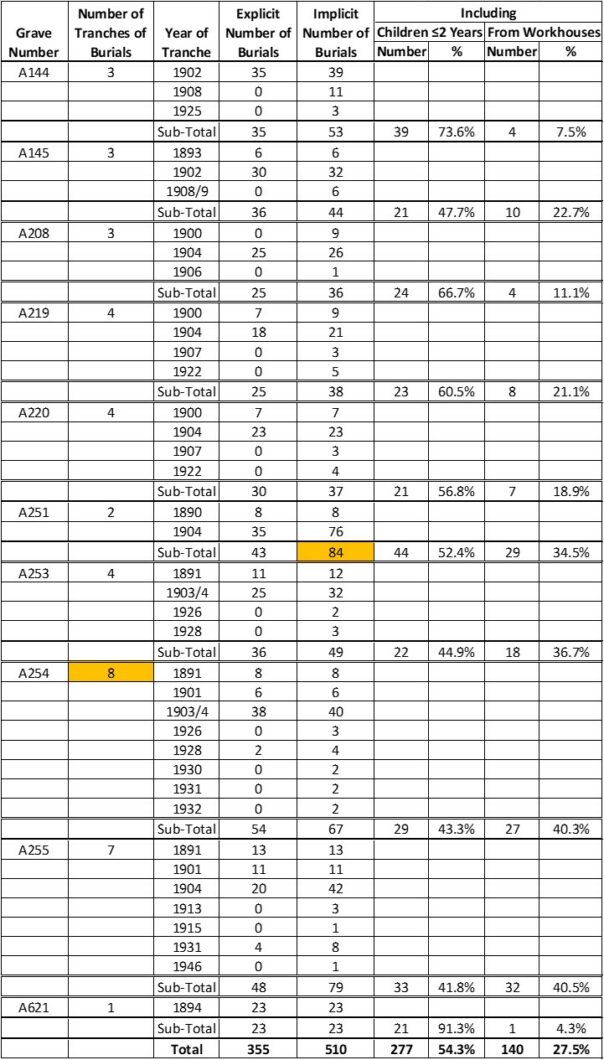

In practice, the RPCC not only flouted with burial laws but also with what was considered ‘respectable’ behaviour to the graves of the deceased and their relatives. Class A interments, the ‘common graves’ which made up 17,590 (71 percent) of the 24,809 burials, were clearly the most precarious. They were physically unmarked and in practice these graves were repeatedly desecrated in order to add new burials to the plots, sometimes over several decades. Table 5 presents the top ten Class A common graves in terms of multiple interments.[ 26 ]

The first number of note is that these ten plots contained 510 bodies and one plot alone (A251) had 84 corpses interred within it.[ 27 ] The tranches refer to the number of times the bodies were disturbed to add more corpses, and the year when this occurred. So, for example, plot A254 was disturbed eight times between 1891 and 1932 to bury and rebury 67 bodies. What is noticeable is that over half (54%) of the burials are children under the age of 2 years and more than a quarter (27%) are designated as from ‘workhouses’. This pattern maybe accentuated as this is a small but extreme example, but it suggests that multiple interments were the norm for Class A ‘common graves, and they contained a large proportion of infants and those from the workhouse.

So, what of the category B-E burials? Table 6 provides the data on the numbers of interments for each class of grave. It is of note that only 22 Class E, the most expensive (and protected) ‘walled graves’, were purchased. Of the grouped categories, B-E, which amounted to 7,049 burials (28.4% of the total), only about a third (36.7%) were marked with a monument of some sort. This leaves us with the astounding result that only around 10% of the burials were marked on the surface by a memorial of some sort.

It appears that Class B to D burials were treated in a similar manner as Class A, but not to anywhere near the same scale of stacking. This is borne out by answering a remaining question as to whether graves with a memorial, be it stone, statue, plinth or vault, were less likely to be repeatedly desecrated with the introduction of bodies of non-relatives. Of course, such expensive adornments were typically the province of the better off in Victorian and Edwardian societies. Did wealth provide protection from these dubious burial practices?

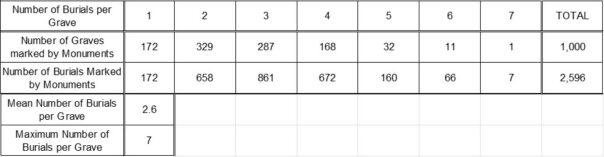

Table 7 provides an analysis of all the graves marked by memorials at Ridgeway Park cemetery and the numbers of burials in each. It would be expected that these kinds of plots would contain several family interments. This is supported by the average of 2.6 burials per grave and a maximum of 7. These figures should be compared with those for Class A ‘common graves’ which are far higher, sometimes an order of magnitude greater. This suggests that paying for a memorial in a Class B-E grave provided significant protection from multiple interments of non-family, unrelated bodies.

In his comprehensive survey of Ridgeway Park cemetery and the company that owned it, John Butland Watts notes that:

Presumably because of the commercial aspect of its operations, the RPCC often “re-used” graves, and in the case of Common Graves, they were “re-used” over and over again. Even in the case of Private Graves, if a customer failed to pay the fee for the lease, or if the lease expired, or if a grave owner discontinued their interest in a particular grave (e.g. because they planned to emigrate), the RPCC was quick to re-use the grave, whether as a Private Grave once again, or as a Public Grave.[ 28 ]

The commercial aspect of the operation of private cemeteries such as Ridgeway Park is of course central to understanding burial practices. The lack of significant regulation and the unrestrained free market of Victorian Britain incentivised cemetery owners to ‘pack and stack’ to an extraordinary degree. Deals with institutions such as Poor Law Unions would have been sought after as relatively long-term, ‘bread and butter’ contracts, supplying regular batches of pauper bodies and thus regular payments. The sliding scale of charges for leases on burial plots played to the better-off in local communities as insurance against practices of packing and stacking in ‘common graves’. After all, a wealthy customer when they visited the grave of a loved-one would want to be confident that the body was actually there, that the grave had not been recently desecrated to add an unknown number of unrelated corpses to the plot.

The free market also led to competition between cemeteries, which in turn encouraged ‘packing and stacking’. There is evidence from 1934, for example, that the RPCC was directly competing with Greenbank cemetery, having to reduce its prices for burial by 5s in order to undercut its municipal neighbour’s new pricing scale.[ 29 ] As the new private cemeteries filled through the Victorian and Edwardian eras, the pressure to make profits for the shareholders would have encouraged the use of every piece of the available land, both horizontally and vertically. The unclaimed pauper body would have been at the mercy of this brutal search for profit, at the very bottom of a sliding scale of monetary importance and with few family members able to question its actual whereabouts.

It has been calculated by Watts (see Table 6) that of the 25,809 people buried in Ridgeway Park cemetery, 22,225, almost 90%, are in unmarked graves. This is a staggering figure, not just the number of bodies that have been ‘packed and stacked’ into this site, but the vast majority that remain hidden beneath the surface of this cemetery without a marker. Eugene Byrne noted in his recent article in Bristol Times on the rediscovering of Ridgeway Park cemetery:

Forgotten also, perhaps, because most of those commemorated here were from the surrounding neighbourhood, a working-class area where few of the cities elite lived. Unlike other Bristol cemeteries dating from Victorian times, Arnos Vale, Greenbank and Avonview for instance – it has hardly any grand grave monuments.[ 30 ]

We would go further and say that we need to change the way we look at Victorian and Edwardian cemeteries, both private and public, to grasp the inequalities in treatment of the working-class in the period and how this fashions the landscape. Currently, we see the vista of the ‘named’ deceased marked by memorials from the grandiose to the mere grave stone, in the pleasant and apparently ordered setting of the cemetery. Instead, we are actually looking at a metaphorical iceberg, where 9/10 of the ‘truth’ lies below the surface, hidden from view and hidden from history.

From Ridgeway Park to Greenbank Cemetery

In contrast to the privately owned Ridgeway Park cemetery, Greenbank cemetery was the project of the St Philip’s Burial Board (SPBB) set up in 1868. The SPBB required a significant amount of space for burials to service the large and densely populated outparish of St Philip & Jacob. Opened in 1871, Greenbank cemetery was extended by the SPBB in 1880 and then in 1895, after the extension of the city boundary to include the outparish of St Philip & Jacob, became the responsibility of the Corporation under the Bristol Corporation Act of that year.[ 31 ]

The key question is, were similar practices of packing and stacking of bodies employed at Greenbank cemetery, and to what degree? One simple check to provide at least an estimate of such practices is to compare the area of the cemetery with the number of people buried there. The records of Greenbank cemetery state that the number of burials for the period 2 July 1871 – 31 October 1991 is 108,439. Taking the area of Greenbank cemetery quoted on the 1949-1965 Ordnance Survey map of 32.20 acres (equivalent to about 130,000 m2) and dividing this by an estimate of grave size (1.39m2), assuming a standard of 6 ft x 2.5 ft, gives the absolute maximum space for around 93,000 burials.[ 32 ] In practice this would be significantly less due to the need for some spacing and for paths and buildings. This estimate suggests that pauper bodies may have been tightly ‘packed’ at Greenbank cemetery but perhaps not as ‘stacked’ as much as they were at Ridgeway Park.

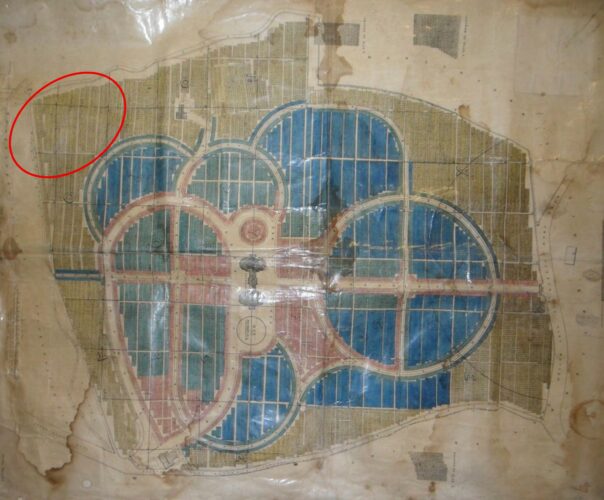

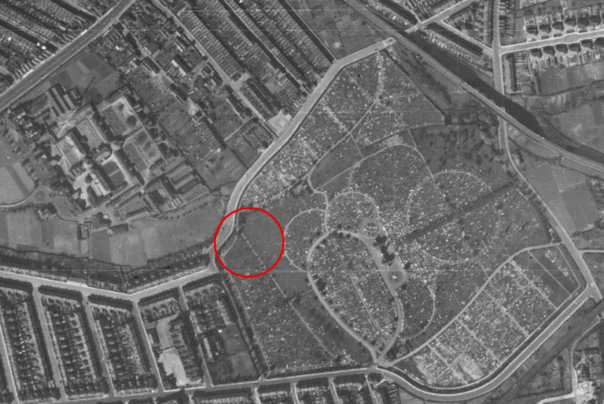

Another clue to the arrangement of bodies at Greenbank comes from studying the available burial maps. Figure 3 is a low-resolution image of a map taken from the wall of the Greenbank cemetery workers lodge in 2015. The area marked with the red circle is the slope running down to Rosemary Green. According to the diagram this area is packed with burials. This should be compared to Figure 4 an aerial photograph taken in 1949 which shows few, if any visible burials in that area, and Figure 5 which shows the area of interest from the ground. In both cases the appearance is of an empty part of the cemetery, with no markers or sign of the mass of pauper burials that lie beneath. Estimating from the burial map suggests that in this single corner of Greenbank cemetery, close to Rosemary Green, there could be more than 1,000 unmarked burial plots. This figure corresponds with the 962 unclaimed pauper bodies from Eastville Workhouse that were interred in Greenbank Cemetery from 1906-1914.

John Butland Watts has also suggested that the colour scheme shown in Figure 3 and in the Greenbank Cemetery records correlates to some degree with the categories at Ridgeway Park. He indicates that the colour yellow at Greenbank approximates to the ‘Class A’, common graves at Ridgeway, whereas the colours green, blue and pink at Greenbank are similar to Classes B to E, at Ridgeway. This makes complete sense with the higher value ‘pink’ plots (Classes D and E) being closer to the centre of the cemetery and the elegant chapel at the top of the hill, surrounded by the blue and green Class B and C graves. Whereas the farthest extremities of the site were the province of the yellow, cheaper private and common graves lower down the hillsides. This is further supported at Greenbank by the prevalence of the most extravagant memorials being in the ‘wealthy’ pink areas at the top of hill.

A small sample survey, carried out by John Butland Watts on Greenbank cemetery data based on these colour designations, has suggested that the ‘yellow’ graves had between 1 and 20 bodies buried in them in up to seven tranches. In contrast, burials in the blue, green and pink graves made up less than 14% of the total and had only up to four bodies interred in each.

Summary

All this evidence suggests that the vistas of both private cemeteries in the period, like Ridgeway Park and public cemeteries, like Greenbank are very misleading. What we see in terms of physical markers such as grave stones, tombs and gothic statues mark the boundaries of social class in the Victorian and Edwardian periods, hiding a great deal more than they expose. Large sections of the working class, from the paupers forced by destitution into the workhouse, to those working in abject and chronic poverty, the so called ‘deserving poor’, and the better-off ‘respectables’ were often treated similarly in death. Their burials are generally unmarked, ‘packed and stacked’, sometimes to a ridiculous degree, and often desecrated numerous times for the purposes of financial gain or cost cutting. If you could not afford it, the chances of a retaining a single familial burial plot for more than a few years were very low.

The idea then that we can ‘find’ the burials of our recent ancestors in the Victorian and Edwardian periods if they came from working class backgrounds is open to question. Yes, it is likely we can ‘find’ them on our computers, through the bureaucratic obsessions of the Victorian and Edwardian eras and the valiant efforts of family historians in the twenty-first century to transcribe burial records and death registers. Finding them in actuality, is a far more difficult task.

In discussions with cemetery keepers at Greenbank and Avonview several years ago, it became clear that finding unmarked graves was not an easy task even if maps existed. If you did manage to find the approximate location, then the latest evidence suggests you might be searching through the remains of dozens of people, hundreds in the case of mass common graves.[ 33 ]

As with World War One Commonwealth war graves on the western front, with their neat plots and white crosses, today’s impression of Victorian and Edwardian cemeteries is of order, memorialisation and respect. It appears as if each soldier (or civilian) has their own resting place and their individuality restored. The reality based on the evidence uncovered here is starkly different. Someone once said:

The working class have no country, the only land they have is the six foot they are buried under.

Well, it seems the free market capitalism of the Victorian and Edwardian eras denied even this.

Acknowledgements

This article would not have been possible without the research undertaken by members of the Eastville Workhouse Memorial Group over several years particularly by Gloria Davey, assisted by Di Parkin and Trish Mensah. In addition, the advice, criticism and hard work of John Butland Watts, Project Coordinator for the Bristol & Avon Family History Society, has been invaluable. Thanks also to Matt Coles and the staff at Bristol Archives for providing vital help with the sources, Dr Molly Conisbee for her advice, Eugene Byrne for his support and the ‘cemetery huggers’: Kate Clements, John Jenkin, Richard Collins and Ruth Symister, who make up some of the Friends of Ridgeway Park Cemetery crew.

- [ 1 ] Consecration fees paid to the diocese of the Church of England were significant. In 1868 the Clifton Poor Law Union paid a “scandalous and disgraceful” consecration fee of £50 for extending the burial ground. Relative to wages and income this is equivalent in 2024 to £41,200 using the average earnings and £55,400 using per capita GDP. Roger Ball, Di Parkin, Steve Mills 100 Fishponds Road: Life and death in a Victorian Workhouse, 3rd edition (Bristol: BRHG, 2020) p.179; Lawrence H. Officer and Samuel H. Williamson, “Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present,” MeasuringWorth, 2025. [back…]

- [ 2 ] See Figure 34 in Ball et al, 100 Fishponds Road p. 182. [back…]

- [ 3 ] Taken from Know Your Place – Bristol – 1894-1903 OS 25” 2nd edition. [back…]

- [ 4 ] Ridgeway Park cemetery is located on Oakdene Avenue, Eastville, Bristol, BS5 6QQ [back…]

- [ 5 ] Bristol Archives Guide to cemetery and burial records (Bristol: Bristol Archives, n.d.) p. 16, 18. [back…]

- [ 6 ] Arnos Vale cemetery is located on Bath Road, Brislington, Bristol, BS4 3EW. [back…]

- [ 7 ] Bristol Archives Guide to cemetery and burial records p. 11. [back…]

- [ 8 ] For more on the semi-legal sale of bodies by PLUs see Ball et al, 100 Fishponds Road pp. 171-173. [back…]

- [ 9 ] Bristol Mercury, 21 March 1896 [back…]

- [ 10 ] Bristol Mercury, 9 February 1878 [back…]

- [ 11 ] Bristol Mercury, 21 March 1896 [back…]

- [ 12 ] Bristol Archives 30105-3-4, Registers of deaths, 4 Jan 1889 – 15 Jun 1898. [back…]

- [ 13 ] Ball et al, 100 Fishponds Road p. 173 [back…]

- [ 14 ] For more on friendly societies see Carlos Guarita, Friendly Societies Against The Big Society, Bristol Radical History Group (2013). [back…]

- [ 15 ] Bristol Municipal Cemeteries: Burial Registers Volume 1 Greenbank Cemetery 2 July 1871 – 31 October 1991 (Bristol: Bristol and Avon Family History Society, 2014). [back…]

- [ 16 ] This information can be downloaded from the Bristol and Avon Family History Society at Bristol Municipal Cemeteries: Burial Registers Volume 2 – Index and Transcripts: Avonview, Brislington, Canford, Henbury, Ridgeway Park and Shirehampton. (Bristol: Bristol and Avon Family History Society, 2019). [back…]

- [ 17 ] Ball et al, 100 Fishponds Road p. 179 [back…]

- [ 18 ] Ball et al, 100 Fishponds Road p. 193] [back…]

- [ 19 ] Ball et al, 100 Fishponds Road p. 185] [back…]

- [ 20 ] Ball et al, 100 Fishponds Road p. 176] [back…]

- [ 21 ] My thanks go to Dr Molly Conisbee for clarifying this issue [back…]

- [ 22 ] Eugene Byrne, Bristol’s forgotten cemetery – The hidden history of burial site, Bristol Times – Bristol Post, 15 July 2025. [back…]

- [ 23 ] 12s in 1919 is equivalent to about £132 today (2024), relative to average wages. Officer and Williamson, MeasuringWorth 2025. [back…]

- [ 24 ] Classes D and E are further subdivided into D1, D2, E1 and E2, with the implication that the numbers 1 and 2 applied to different Sections of the Cemetery, each with different charges. [back…]

- [ 25 ] John Butland Watts, Re-mapping Ridgeway Park Cemetery – Notes to Accompany the Re-Created Grave Number Plans of the Various Sections of Ridgeway Park Cemetery (Bristol: BAFHS, 2018). [back…]

- [ 26 ] My thanks go to John Butland Watts for providing the analysis in Tables 5, 6 and 7. [back…]

- [ 27 ] The ‘implicit’ burials are those where a lack of clerical data has been overcome by studying the burial records and adding on to the ‘explicit’, recorded values. [back…]

- [ 28 ] Watts, Re-mapping Ridgeway Park Cemetery. [back…]

- [ 29 ] Watts, Re-mapping Ridgeway Park Cemetery. [back…]

- [ 30 ] Eugene Byrne, Bristol’s forgotten cemetery, Bristol Times in the Bristol Post, 15 July 2025. [back…]

- [ 31 ] Bristol Archives Guide to cemetery and burial records (Bristol: Bristol Archives, n.d.) p. 16. [back…]

- [ 32 ] Bristol Municipal Cemeteries: Burial Registers Volume 1 Greenbank Cemetery 2 July 1871 – 31 October 1991 (Bristol: BAFHS, 2014) p. 9; Know Your Place – Bristol – 1949-1965 OS National Grid. [back…]

- [ 33 ] For the mass common graves at Avonview cemetery, the resting place of thousands of paupers from Eastville Workhouse, see Ball et al, 100 Fishponds Road, pp. 185-189. [back…]