Our dead are never dead to us, until we have forgotten them[ 1 ]

Introduction

One evening in 2010 some members of Bristol Radical History Group (BRHG) were poring over some old maps of Eastville and discovered a forgotten burial ground at Rosemary Green, just round the corner from where they lived. Further investigation showed that the site was in fact the burial ground for Eastville Workhouse at 100 Fishponds Road, an enormous institution that had opened in 1847 and whose buildings were demolished in 1972 to make way for the East Park housing estate.

After several years of research in Bristol Archives, BRHG members gathered details of over 4,000 men, women and children from the workhouse who had been buried in unmarked graves at the site. There was no sign or marker of Rosemary Green’s past use as the burial ground for the workhouse; it was a secluded valley used by sunbathers, dog walkers and kids playing football. In the summer of 2014, after a public meeting, Eastville Workhouse Memorial Group (EWMG) was formed with the aim of publishing the details of the forgotten paupers[ 2 ] and raising money for a permanent memorial to mark their final resting place.

From church graveyards to ‘workhouse dunghills’

Research into the origins of the burial ground showed that it had been the product of cost savings made by the penny-pinching Poor Law Guardians who ran the institution. A few years after the opening of Eastville Workhouse the Board of Guardians had balked at the costs of the customary practice of sending bodies of deceased paupers back to their respective parishes of origin for burial. Clifton Poor Law Union, which they oversaw, consisted of 12 parishes mostly outside Bristol city centre to the west, north and east in Gloucestershire, with Henbury and Winterbourne the most distant.[ 3 ] The Bristol Mercury reported that:

the Guardians, and through them the ratepayers, were put to considerable expense in determining where paupers were properly chargeable; an outlay was incurred… in removing the bodies to remote places.[ 4 ]

The Guardians decided instead to use a piece of waste ground next to the workhouse as a burial ground. It was not an ideal location for interments; a steep slope led down to a sewage infested stream, Coombe Brook, which regularly flooded and flowed into the nearby River Frome. However, by ordering inmates to carry shrouded bodies from the workhouse mortuary to unmarked graves dug by them in the burial ground, the Guardians were able to save money on grave-diggers, coffins and horse drawn transport to the parishes. These new burial practices were part of a wider series of measures encouraged by the 1834 Poor Law Act which aimed to reduce the cost of paupers to rate-payers and make the experience of poverty ‘disgraceful’ in life and in death.[ 5 ]

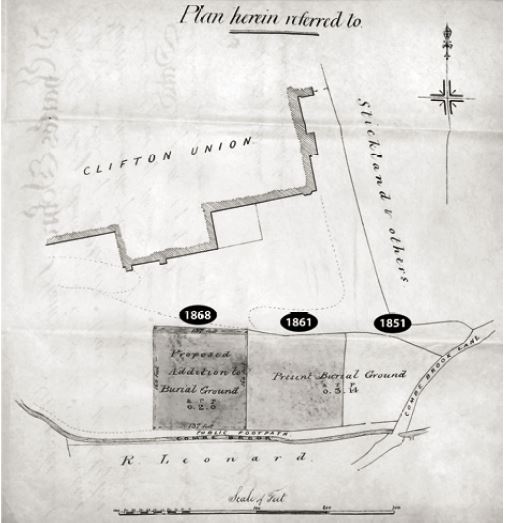

Despite reservations within the clergy in the Victorian period that burials should take place in churchyards and not in the new-fangled ‘public cemeteries’ and opposition from the public who resented paupers being buried in “workhouse dunghills” three pieces of land at Rosemary Green were consecrated in 1851, 1861 and 1868. One of the reasons for the acquiescence of the Bishop of Bristol and Gloucester, who presided over the ceremonies, was the £50 fee the church charged for each consecration; in total equivalent today to around £150,000.[ 6 ] Some Guardians even complained that this was a “scandalous and disgraceful” sum, but despite their protestations the savings still outweighed the costs, so expansions to the burial ground went ahead.[ 7 ]

‘Packed and stacked’

Over the years 1851-1895 more than 4,000 paupers were interred at Rosemary Green. Initially, at least, the unmarked burials were merely packed tightly together horizontally but as each tranche of consecrated ground became full other practices were introduced. These included returning to older parts of the burial ground and carrying out multiple vertical burials, interring bodies under the footpaths and selling bodies to medical schools for dissection. [ 8 ] At the height of a cost-cutting crusade led by the Poor Law Board in London in 1878 the Clifton Guardians made the decision not to expand the burial ground any further by consecration of new land, probably because of the cost of the fees paid to the diocese.[ 9 ] Using the aforementioned methods, several of which contravened legal guidelines brought in to deal with cholera epidemics in the 1840s, pauper bodies were ‘packed and stacked’ into multiple burials on the site until it was deemed full to bursting in 1895.

These burial practices driven by brutal cost-cutting may have been within the workhouse walls but they did not go unnoticed. In 1869 a protest meeting of ‘working men’ held on West Street in east Bristol concerning the callous treatment of paupers in the Clifton Poor Law Union stated that the Guardians:

thought nothing of enlarging their burial ground, and thought nothing of seeing the mounds sticking up, and as soon as they (the poor) cropped up they would put them there.[ 10 ]

Demolition and disinterment

One afternoon in the summer of 2015 as we were surveying Rosemary Green a local resident informed us that he had worked for the company that had demolished the workhouse buildings in 1972. Although he had not participated in the job himself he knew the Managing Director was still in charge of the company and he was sure that he would remember such a major operation. This was an exciting lead, as our researches into the demolition of the workhouse buildings had liberated no more than a couple of newspaper articles and some interesting photographs.

We tracked down the company to their base in Somerset and interviewed the Managing Director and a foreman who both remembered the demolition. The company had been contracted by Bristol City Council to demolish the workhouse buildings and part of the arrangement was to clear the burial ground. This turned out to be a massive job, with excavations lasting weeks in the summer of 1972, apparently overseen by representatives from the church. The site foreman recounted that excavations with mechanical diggers turned up huge amounts of human remains in some cases buried 15 feet deep, with evidence of multiple burials. It was hard to estimate the number of bodies present as the remains were jumbles of bones, but certainly “more than a thousand and possibly thousands”. Only major bones were collected and placed in timber boxes, which were then loaded into a transit van and shipped off to a “cemetery near the Feeder Road”.[ 11 ] The foreman remembered that there appeared to be no coffins amongst the remains and that there were a number of bodies of children. It was clear that delineating individuals was impossible due to the speed and crude method for disinterment. The remaining hundreds of thousands of skeletal fragments mixed with top soil and demolition rubble were then ploughed back onto Rosemary Green raising the ground level by several feet.

The foreman’s recollections helped explain some other memories that had been collected by the workhouse project. One correspondent remembered:

Circa 1972/3 I was working at Cavenham Confectionary Greenbank Bristol. I can recall a worker who had two skulls which he had taken from the site of 100 Fishponds Road. Apparently a lot of human remains were exposed during the ground works for the new housing estate[ 12 ]

Another eye-witness, a child at the time, recalled the ‘timber boxes’, mistaking them for coffins:

As a boy living in Coombe Road I remember the site being excavated before/during the demolition of 100 Fishponds Road. I am pretty sure some of the coffins, more like planks built into boxes, were dug up and removed. We used to dig around in the rubbish and I found a broken mug with the crest of the Bristol Guardians of the Poor…We dug up clay pipes, old glass bottles and various items that were thrown out.[ 13 ]

A teacher who worked at a school adjacent to the site of the workhouse buildings remembered their demolition in 1972. Pupils from the school had been entering the building site through a hole in the fence to look for Victorian bottles that had been turned up by the excavations. Instead they returned to the school with bags full of human bones!

In autumn 2015 we applied for planning permission to site a standing stone memorial on Rosemary Green to mark the site of the unmarked graves. From our survey we were confident the memorial was situated just outside the original boundary of the burial ground and thus would not interfere with any human remains. However, the revelations of the foreman of the demolition team suggested that Rosemary Green had been significantly altered by the disinterment and that fragments of bone were scattered over a much wider area than the original consecrated ground. In fact, a few months previously, some builders working on a new house just behind the memorial had found bones and a child’s hobnailed shoe in the foundations. Sure enough, in November that year, during the excavation of a hole to install the memorial stone we found numerous small fragments of human bone which we reburied.[ 14 ] It seemed our witnesses to the demolition were right. The question was, where had the thousands of major bones been moved to?

From Rosemary Green to Avonview

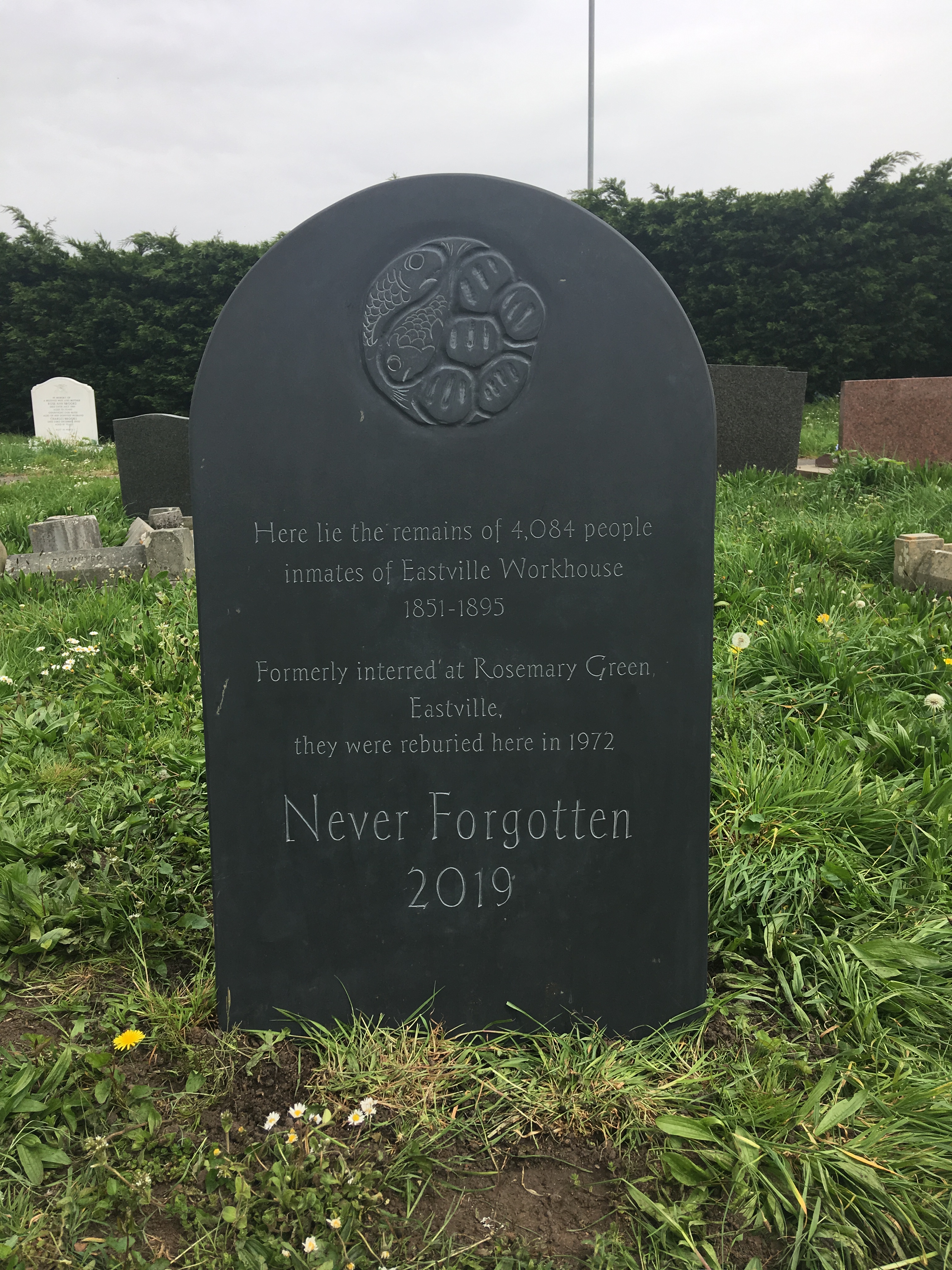

Following the lead of a “cemetery near the Feeder Road” we made enquiries with the Bristol City Council cemeteries and crematoriums service based at Canford. In their archives a Register of Burials stated that 167 boxes of human remains had been recovered from the “Eastville Institution, 100 Fishponds Road” in September 1972 and deposited in three adjacent plots in a corner of nearby Avonview Cemetery in St George.[ 15 ] Excited that we had finally solved the mystery we rushed over to Avonview, and after studying the cemetery map found the ‘common graves’. These were three deep pits that had been filled with the bones of thousands of paupers, and incredibly, left unmarked once again. In fact, without the map we would never have found them. We were shocked, and one member of the group commented: “I can understand this happening in 1872, but 1972, you have got to be joking!”

Having located the final resting place of the workhouse inmates we were keen to pin down who had made the decision to sanction the removal of the human remains from unmarked burials in consecrated ground at Rosemary Green to the unmarked common graves at Avonview Cemetery. Having carefully studied the conveyance, indenture and petition documents for the consecrated ground at Rosemary Green at Bristol Archives we were confident that the dioceses of Bristol and Gloucester retained responsibility for the burial ground.[ 16 ] In fact, as late as 1902, a note had been added to one indenture clarifying this fact. It stated:

an indenture dated the 14th day of April 1851 and made between the Guardians of the Poor of the Clifton Union in the City of Bristol of the one part and the Right Reverend James Henry Lord Bishop of Gloucester and Bristol of the other part A small plot of Ground…was granted unto the said Lord Bishop and his Successors In trust that the said plot of ground should be forthwith consecrated and should for ever thereafter be separated and set apart from all profane uses and be devoted and appropriated by the said Guardians to the burial of bodies of persons who at the time of their respective deaths should be chargeable to the said Union or to any Parish comprised therein and according to the Rites and ceremonies of the United Church of England and Ireland And whereas the said plot of ground was duly consecrated as appears by Act of Consecration dated 24th April 1851 Now it is hereby declared that the within Conveyance shall be taken to have been made subject to the said Indenture of the 19th day of April 1851 and to the provisions for burial therein mentioned so far as relates to the small plot of ground thereby granted and the consecration thereof.[ 17 ].

Having proved that the burial ground at Rosemary Green was both consecrated and held in trust by the dioceses and checked the legal requirements for disinterring bodies it seemed reasonable to assume that the church had taken the decision to allow the removal of the remains in 1972. In January 2016 we wrote to the Bishop of Bristol asking the diocese to provide evidence for the disinterment, accept responsibility for this decision and suggesting they should mark the common graves at Avonview with a memorial. [ 18 ] Unfortunately, the responses were somewhat negative, to say the least. The Bishop claimed that:

checking the Diocesan Registry departments of both this diocese and the diocese of Gloucester has revealed nothing that connects the Church of England with the churchyard concerned. We have also heard, that no ceremony was involved at the time the remains were dug up, and secondly, that this was done by a JCB-like bulldozer. I have to say, I think it is almost inconceivable that the church would have anything to do with such an outrageous approach…this really does have the feel more like property developers who may or may not have sought the proper permissions.[ 19 ]

The Bishop continued his Pilate-like response by offering a “without prejudice” contribution to the cost of a memorial. In a subsequent letter from the Acting Archdeacon of Bristol their position was reinforced:

I am sorry to confirm, however, that we cannot locate any records (either in this diocese, or in the diocese of Gloucester) which would support the building contractors’ comment that the Church of England in any formal way ‘oversaw’ the events of 1972.

Although it is clear that the site of Rosemary Green falls within what is now the Parish of St Anne with St Mark and St Thomas, Eastville, it does not appear to have been Church land (i.e. not a churchyard for which the local Parish Priest for example, would have had any responsibility) and the Diocese would not therefore have had any legal involvement in its sale or development for housing.[ 20 ]

The denial that the burial ground at Rosemary Green was a ‘proper’ graveyard; that is, in the grounds of a church under the auspices of a ‘Parish Priest’, carried great historical irony for us. In 2016 the Church of England were denying that a “workhouse dunghill” had any status as consecrated ground. “Didn’t stop them taking over a hundred grand in consecration fees though, did it?” commented one angry member of EWMG when he read the letter. He added “Are they going to give that back?”

Whodunnit?

For many of us in EWMG the refusal of the Church of England to take full responsibility for either the burial ground or the decision to remove the thousands of pauper bodies to Avonview was very demoralising. In July 2016, with the help of local stone mason Matthew Billington, we had even presented the dioceses of Bristol and Gloucester with a detailed proposal and a design for a memorial to mark the common graves at Avonview but to no avail. Between them they offered less than a quarter of the £3,000 of the cost as a donation. Over 2015 and 2016 EWMG members and local residents had worked very hard to raise £10,000 from trade unions, local institutions and businesses to fund a memorial at Rosemary Green, a plaque to mark the location of Eastville Workhouse and projects with local schools. Why should local people have to fork out again to pay for a decision that had apparently been made by the Church of England and to a lesser degree, Bristol City Council? With the proposal stalled, plans to memorialise the mass common graves at Avonview went into hibernation for two years.

The failure to get to the bottom of who was responsible for the decision in 1972 and to memorialise the final resting place of the paupers bothered us. Despite all the years of work on the Eastville Workhouse project, it still felt incomplete. Consequently, in the autumn of 2018 it was agreed to approach the dioceses again. In the two years that had passed, the Archdeacon had retired and the Bishop had moved on. We resent the letters and proposals to the incumbents and, lo and behold, the evidence we were after finally turned up. In late October a meeting took place at Rosemary Green and Avonview Cemetery between members of EWMG and Michael Johnson the new Acting Archdeacon to discuss the proposal for a memorial. A few days after, Johnson more than doubled the donation to the memorial and crucially sent us a copy of a ‘faculty’ document from 1972, effectively a legal authorisation within the Church of England. This document sanctioned the City Engineer to carry out:

The removal of human remains from the disused burial ground at 100 Fishponds Road Bristol and the reinternment of the human remains in Plot AA at Avonview Cemetery Bristol.[ 21 ]

The person who signed off the decision to move the bodies from one unmarked burial site to another was David Charles Calcutt esq. Calcutt, a high flying establishment barrister, judge, Professor of Law and Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge was also Chancellor of the Church of England dioceses of Exeter and of Bristol from 1971-2004. Calcutt, who passed away in 2004, was described in his obituary as one who’s:

search for excellence was beyond compare, his determination was formidable, and his simple humanity was frequently unrecognised…Calcutt always had the common touch.[ 22 ]

It appears he failed to apply any of these traits to the treatment of the remains of more than 4,000 men, women and children buried at Rosemary Green, when he consigned them to nameless oblivion in a forgotten corner of Avonview Cemetery.

Putting things right…again

And so began the last stage of our project; to mark the final resting place of the forgotten inmates of Eastville Workhouse. We had started out wanting to put right the disrespect Victorian society had shown to the paupers in life and in death, and ended up having to deal with the same attitudes a century later. Three years after our shocking discovery, on May 8th 2019, The Lord Mayor, Archdeacon of the Diocese of Bristol and the Deputy Mayor joined us and relatives of those who were buried at Rosemary Green to unveil a memorial to mark the common graves. Apart from the donations from the Bristol and Gloucester dioceses (which amounted to £1,700), Eastville Workhouse Memorial Group added £500 and Bristol City Council made up the final £800. The weather during the unveiling was ‘biblical’ from start to finish, with thunder, lightning and then hail lashing down. Most of us thought it apt. However, we were left with a lingering thought: this couldn’t happen again, could it?

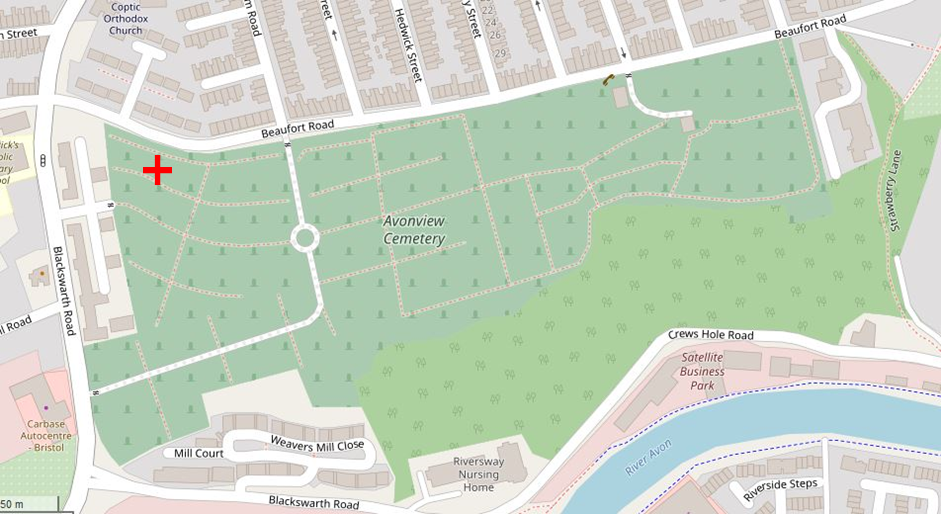

The memorial to the mark the common graves at Avonview Cemetery (Beaufort Rd, Bristol BS5 8EN) can be found in the north western corner, between Blackswarth Road and Beaufort Road. It is marked with a red cross on the following map.

A shorter, more sanitised version of this article appeared in the Bristol Times section of the Bristol Post on Tuesday 28th May, 2019.

You can read more about Eastville Workhouse and the burial ground at Rosemary Green in the Bristol Radical History Group book: 100 Fishponds Rd: Life and Death in a Victorian Workhouse by Roger Ball, Di Parkin and Steve Mills (2016).

Thanks to all those in Eastville Workhouse Memorial Group who have persevered with this project over the last five years.

- [ 1 ] George Eliot quoted from Pike, B. et al 100 Fishponds Rd 9:42 http://www.brh.org.uk/site/articles/100-fishponds-road/. [back…]

- [ 2 ] A full list of these burials can be found at https://www.brh.org.uk/site/articles/rosemary-green-burial-ground-data/. [back…]

- [ 3 ] Ball, R., Parkin, D. and Mills, S. 100 Fishponds Rd: Life and death in a Victorian Workhouse, Bristol: BRHG, 2016 pp. 29-30 & Fig. 4. [back…]

- [ 4 ] Bristol Mercury 26 April 1851. [back…]

- [ 5 ] These policies are discussed in much greater detail in Hurren, E. T. Protesting About Pauperism: Poverty, Politics and Poor Relief in Late Victorian England 1870-1900, Suffolk: Royal Historical Society, 2015. [back…]

- [ 6 ] Using the GDP per capita conversion, £50 in 1851, 1861 and 1868 was worth in 2018 £63,370, £48,070 and £42,870 respectively. “Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present,” MeasuringWorth, 2019. URL: www.measuringworth.com/ukcompare/. [back…]

- [ 7 ] Bristol Times & Mirror 17 October 1868, Western Daily Press 24 October 1868 and 5 December 1868. [back…]

- [ 8 ] The practice of ‘giving’ bodies to medical schools began at Eastville workhouse in 1872 and continued until 1894. In all 118 deceased men and women suffered this fate. Ball et al, 100 Fishponds Rd pp. 171-172. [back…]

- [ 9 ] Bristol Mercury 29 June 1878. [back…]

- [ 10 ] Bristol Mercury 19 January 1869 [back…]

- [ 11 ] The Feeder Road runs parallel to the Feeder Canal in St Philips Marsh in East Bristol. [back…]

- [ 12 ] E-mail to BRHG 20 January 2015. [back…]

- [ 13 ] J. Clevely E-mail to BRHG 9 February 2015. [back…]

- [ 14 ] Pike, B. et al 100 Fishponds Rd 6:00-6:15 Bristol: Pauper Productions, 2016 http://www.brh.org.uk/site/articles/100-fishponds-road/. [back…]

- [ 15 ] The Register of Burials for Avonview Cemetery is held at Canford Cemetery & Crematorium Office, Bristol. Dated 15 September, 1972 the plot reference numbers at Avonview Cemetery are 1458/A/Light Blue/AA, 1459/A/Light Blue/AA and 1462/A/Light Blue/AA. [back…]

- [ 16 ] Bristol Archives Refs. EP/A/22/CU/1a-c, EP/A/22/CU/2a-b, EP/A/22/CU/3a-b, 42228/1/1/1-2, 42228/1/8/1-3, St PHosp/183-5, St PHosp/190, St PHosp/194 and St PHosp/198. [back…]

- [ 17 ] Bristol Archives Reference St PHosp/198. [back…]

- [ 18 ] Letter from Eastville Workhouse Memorial Group to the Bishop of Bristol, 22 January, 2016. [back…]

- [ 19 ] Letter from Rt Revd Mike Hill (Bishop of Bristol) to Eastville Workhouse Memorial Group, 29 January, 2016. [back…]

- [ 20 ] Letter from Venerable Christine Froude (acting Archdeacon of Bristol) to Eastville Workhouse Memorial Group, 9 February, 2016. [back…]

- [ 21 ] St Thomas the Apostle, Eastville, Faculty No. 1716, 10 March, 1972. [back…]

- [ 22 ] Rawley, A. “Sir David Calcutt: Barrister in favour of controls on the press” The Independent 14 August, 2004. Retrieved from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/sir-david-calcutt-39022.html. [back…]

Dave Marsden

Thanks for both an excellent article and book and for pursuing this sorry and sordid affair to an appropriate conclusion.

However the last remark about it ‘not happening today’ should be borne in mind given the current situation we find ourselves in.

Top work by all involved.

Anwyl Cooper-Willis

I have been looking through a spreadsheet on admissions to the Bristol Lunatic Asylum and have found a number of people mentioned in your data on those buried at Rosemary Green. There is much fuller information on these people which was found in the medical notes of the people in queston. Some of the details differ slightly from what you have. I would be happy to pass on what I have if anyone is inetrested.