Finding epidemics

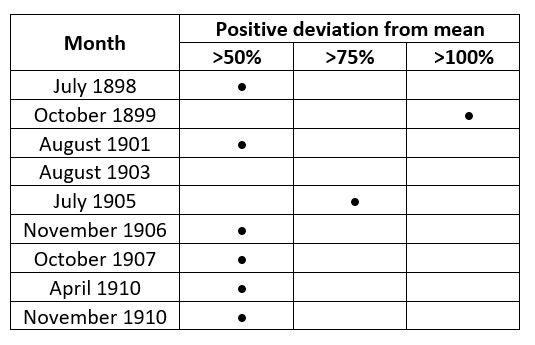

During the collation of Eastville Workhouse death register data for the years 1895 to 1914, the researchers noted some unusual clusters of deaths, particularly amongst the young. In a similar manner to our survey in the Victorian period (1851-1895)[ 1 ] a simple method was developed for determining possible epidemics of fatal diseases amongst the inmates. In order to remove the effect of seasonal variations in death data and the increasing numbers of inmates in the workhouse over the period, the fractions of deaths per month in each year were compared with the mean fraction over the 18 year period (1896-1913).[ 2 ] Positive deviations of 50, 75 and 100 percent greater than the mean fraction of deaths over the period for a given month were flagged and are shown in Figure 1.

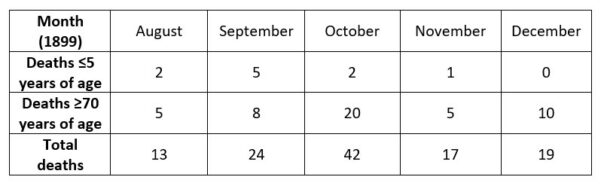

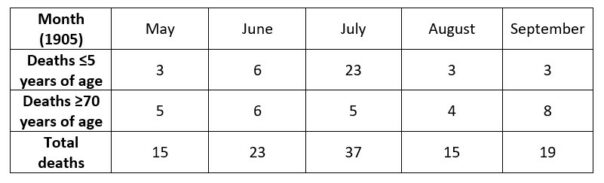

The two months where the deviation from the mean is greater than 75 and 100 percent, October 1899 and July 1905 respectively, were studied in more detail. Typically, the most vulnerable to epidemics of contagious disease are the very young and the very old. The deaths of those less than five years of age and greater than 70 in contiguous months for 1899 and 1905 are displayed in Figures 2 and 3.

Influenza

The data for 1899 in Figure 2 shows a large increase in deaths of elderly inmates suggesting an epidemic in October of that year. This more than doubles the numbers of deaths of those over the age of 70 years compared to the months of September and November. The deaths amongst the very young appear to be unaffected.

A survey of newspapers in the Bristol in the autumn of 1899 shows that an epidemic of influenza was raging through the city and its environs in October and November.[ 3 ] Unlike many other contagious diseases which principally affected the poorer sections of the working class, due to overcrowding, bad sanitation, malnutrition and lack of health care, this epidemic was less class specific. Indeed, ‘The Talk of Bristol’ column in the Bristol Mercury, usually only concerned with social lives of the ‘well to do’, commented at the end of October:

There has rarely been time when we have had more cases of sickness in all parts of the city than at the present moment. Certainly there never was time when so many city men have been laid aside by illness.

The article continued:

There is no doubt that cases of influenza are exceptionally prevalent not only in Clifton but in the south division of the city. We hear of some instances in which whole families have been struck down simultaneously with the fell disease. It was stated last week that as many as nine members of the staff of one of the local banks have been away from business owing to attacks of influenza.[ 4 ]

One of the reasons for the rapid spread in Clifton was probably the annual bazaar at Wesley Hall on Durdham Down. The Reverand J. S. Simon opened the event on 1 November, with the ominous joke:

[Simon] said it was very unfortunate that an epidemic of bazaars coincided with an epidemic of influenza, and he was a victim to the coincidence.[ 5 ]

Various newspaper articles reported in some detail on establishment figures who were confined to their beds with feverous temperatures and ‘pleuro-pneumonia’. These included the deputy coroner, aldermen, well-known businessmen, several Clifton ‘Ladies’ of repute, the Archdeacon, a Bishop, and the ex-Postal Superintendent, some of whom were literally at death’s door or who had already passed away.[ 6 ]

From these reports, the most vulnerable to the ‘Flu’ were the elderly and/or infirm. This was noted by the Medical Officer for Bristol, David Davies, at the end of the first week of November, when he announced that there had been at least 28 deaths in Bristol over the previous fortnight.[ 7 ] Unsurprisingly, the newspaper ‘celebrity’ columns were less concerned with the ravages of influenza amongst the working class, and certainly not the workhouse.

The data in Table 2 suggests that influenza penetrated the closed environment of Eastville workhouse in September, reached its peak in October and was dying away by the end of November. It is unclear how many elderly people died in the workhouse as a result, but a reasonable estimate would be several dozen ‘excess deaths’ over the autumn of 1899.

Measles

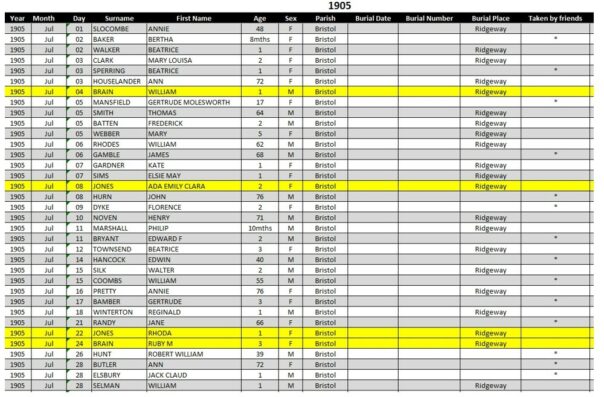

In contrast to the data for October 1899, the figures for July 1905 in Figure 3 show a huge increase in deaths of those under five years of age over a very short period. This suggests the presence of an epidemic of a highly contagious disease amongst the very young. Studying the death register transcript for July 1905 provides more evidence (Figure 4). The deaths of William Brain (aged 1) on 4 July and Ruby Brain (aged 3) on 24 July and perhaps, Ada Emily Clara Jones (aged 2) on 8 July and Rhoda Jones (aged 1) on 22 July are signs of rapid (and deadly) contagion amongst family members.

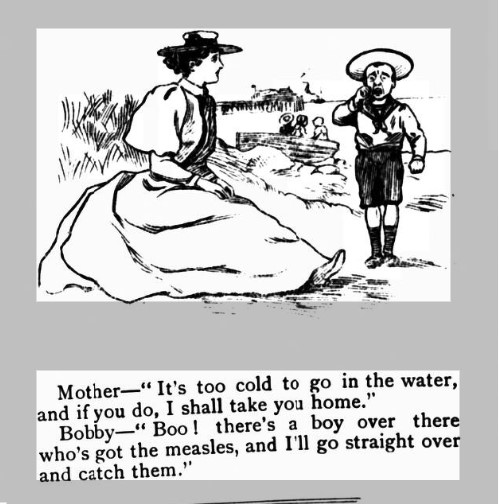

A survey of local newspapers for July 1905 shows that a measles epidemic ‘of a severe type amongst the children’ was underway in Eastville Workhouse. According to the Bristol Times and Mirror it had appeared:

…in the intermediate nursery and the hospital wards, introduced in early June by cases newly admitted to Eastville. Fifty-eight children caught the infection, and 16 had died, the majority of these being very young and delicate children, who were suffering at the time from other serious complaints.[ 8 ]

The Western Daily Press noted that the outbreak of measles in workhouse had now spread into the district of Eastville and that it was being discussed by the Bristol Health Committee.[ 9 ]

An epidemic of the most contagious common disease in the world, measles, was truly deadly in the confined environment of the workhouse, particularly when it penetrated the nurseries and children’s wards.[ 10 ] The Bristol Times and Mirror article suggests a death rate amongst the very young inmates of around 28 percent, more than one in four. This corresponds with medical statistics for the 1920s or countries today with high rates of malnutrition and poor healthcare. These figures do not consider those children with long term health effects due to non-fatal complications as a result of measles, such as brain damage, blindness, and hearing loss.

In February 2025, it was reported by the BBC that data published by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) showed Bristol had the highest number of measles cases in the country this year and by June the city had 11 percent of all cases across England.[ 11 ] With the recent fall in measles vaccine uptake, and the consequent rise in cases of measles, deadly epidemics like that which occurred in Eastville Workhouse in July 1905 should be a salutary lesson to those who deny the efficacy of vaccines.[ 12 ]

- [ 1 ] This earlier methodology is explained in Roger Ball, Di Parkin, Steve Mills 100 Fishponds Road: Life and death in a Victorian Workhouse, 3rd edition (Bristol: BRHG, 2020) p. 162 n. 386. [back…]

- [ 2 ] The data for the years 1895 and 1914 was incomplete and was removed from the sample. [back…]

- [ 3 ] There were also reports of influenza epidemics in Kingswood, Portishead and Warmley, as well as in the workhouse in Trowbridge. [back…]

- [ 4 ] Bristol Mercury, 31 October 1899. [back…]

- [ 5 ] Bazaars were all the rage at the time. Bristol Mercury, 01 November 1899. [back…]

- [ 6 ] Western Daily Press, 02 November 1899; Clifton Society, 09 November 1899; Bristol Mercury, 31 October, 14 November 1899. [back…]

- [ 7 ] Bristol Mercury, 8 November 1899. [back…]

- [ 8 ] Bristol Times and Mirror, 15 July 1905. [back…]

- [ 9 ] Western Daily Press, 19 July 1905. [back…]

- [ 10 ] For more on contagious diseases and epidemics in Eastville Workhouse see Ball et, 100 Fishponds Road, pp. 160-165. [back…]

- [ 11 ] Bullock, Clara ‘Parents warned as measles cases rise’ BBC News, 18 February 2025; Allsop, Sophia ‘Bristol sees a rise in measles cases’ BBC News, 9 June 2025. [back…]

- [ 12 ] UK Health & Security Agency, Research and analysis – Measles: Historic confirmed cases, notifications and deaths, 4 September 2025. [back…]

Fantastic research with lessons for health officials, politicians and the public today.

This article shows how disease cuts across class, affecting everyone from Clifton’s elite, but far worse to families living in the workhouse. Public health depends on shared responsibility and on recognising how easily illness spreads through everyday social events. The 1905 measles outbreak highlights a truth in that we must prioritise society’s most vulnerable, especially children and the elderly. My grandmother lost the sight in one eye as a child from measles, and several children on her street died from influenza including a mother and her new born child. They had no vaccines.