I interviewed Florence Exten-Hann in March 1973 and this article appeared in the socialist feminist magazine Red Rag (no.3 1973). It draws also on notes she wrote about her life for a Workers’ Educational Association class in 1968. The original article was subsequently reproduced in a collection of my writings, Dreams and Dilemmas, Virago, 1983. I have modified it somewhat for clarity and added some new comments at the end.

My article, ‘She Lived Her Politics’ first appeared in the anarchist paper, Wildcat no.6 March 1975. It drew on the interview I had done with Lilian Wolfe, an article by Sandy Martin, ‘Lilian Wolfe-Lifetime Resistance’, Stratford Women’s Liberation Group’s issue of Shrew Vol. 4, No. 4,1972, along with a letter from John Marjoram, Peace News, 24 May, 1974 and the tribute by Nicolas Walter, Freedom, 25 May, 1974 . It was republished in Dreams and Dilemmas, a collection of my writings (Virago 1983). I have modified it for clarity, corrected some errors and added some valuable new material on Fred Dunn, Tom Keell and Mabel Hope, gleaned from ‘Battlescarred’ libcom.org, the Kate Sharpley Library (KSL) and Eds. Candace Falk and Barry Pateman, Emma Goldman Volume 3 On the Stockport anarchists I am indebted to Nick Heath, ‘Anarchists Against World War One.’ KSL no.78-79 September 2014. I have also added some comments at the end.

Sheila Rowbotham 2018

Florence Exten-Hann: Socialist and Feminist.

Florence Exten–Hann 1891-1973 was active in the suffrage, socialist and anti-war movements.

Florence Exten was born into a socialist family and grew up in the climate of agitation of the late 1890s and early 1900. Her father was one of the first socialists to be elected to Southampton council. She became conscious of class when she was still a young girl while ‘helping my father in elections and visiting the back streets of Southampton’s dockland’. He was a member of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), a Marxist grouping dominated by its leader, the dogmatic and sectarian H.M. Hyndman. Though the local branches were more varied, the central figures in the SDF tended to see Marxism as a doctrine which had to be kept pure from grass roots organizing with people who did not agree with them.

Florence recalled the SDF as dismissing trade union work and her father being forced to resign from the SDF when he appeared on the same platform as a member of the Clarion socialist cycling club. This incident must have caused some commotion in the Exten family because Florence remembered it so particularly. The Clarion cycling clubs played an important social and cultural role in the early socialist movement, organizing camps and outings and bringing socialists of varying views together. The Clarion itself was a paper edited by the journalist Robert Blatchford. He was a brilliant propagandist but his approach to socialism was nationalistic.

Clarion cyclists though were unlikely to be troubled by doctrinal debate as they pedalled off into the countryside. For the young worker or clerk the bicycle was the means of escaping from the daily humdrum of working, for the young woman it symbolized the new freedom of the advanced and emancipated. Some rebels wore clothes that made pedalling easier but were regarded as shocking by most people. Florence recalled,‘ Mother and I rode bicycles and wore bloomers, but had to carry a skirt to put on when riding in a town for fear of being mobbed.’

Florence’s family was not very well off but political ideas and activity were part of everyday life. As Florence put it, ’We were born into the socialist movement’. There was, though, a gap between theories of equality and tacit cultural restraints, for parents carried their own prejudices and were, moreover, aware of how their daughters would be regarded outside the home. These contradictions presented young girls growing up in families like Florence’s with an unevenness which could provoke questioning, if not rebellion against the old ideas of feminine behaviour.

Florence described how she was brought up as an intellectual equal to her brothers. But at the same time her father was a man who believed very strongly in his own opinions and in his role as head of the family. He did not take his daughter’s desire ‘to break out into a career’ very seriously, though it was assumed that Florence would earn her living, for the Extens did not belong to the class which could afford leisurely daughters. So instead of becoming a teacher, which is what she would have liked, Florence went out to work as a clerk.

In the early 1900s shop and clerical workers were organizing for better pay and trying to get their long hours of work reduced. The conditions of their work and the control employers could exert over their lives beyond working hours are vividly described in H.G.Wells’ novel Kipps and in Hannah Mitchell’s autobiography The Hard Way Up. Because of Florence’s socialist background her father encouraged her to join the union, which she did in 1908, aged seventeen. In order to be active in a union a young girl had to have sympathetic parents because the potential restrictions were still so strong. Florence was aware that she was allowed much more personal freedom than most ‘respectable’ young girls of her class.

‘It is difficult now to recall that when I was a teenager one could not walk the streets alone (it was not done). I was considered fast and loose because I used to travel to London alone at this time to attend the Women’s Advisory Council of the Shop Assistants Union at least once a month arriving home at 1.30 in the morning. I had an extremely bad reputation among the neighbours and my parents were told how wrong they were to allow it, fortunately my parents were understanding.’

She was to find that women were not always welcome even when they did become active in the labour movement. ‘Once I turned up at a Trades Council but was prevented from attending solely because I was a woman, though an accredited delegate.’ Moreover many trade unions still excluded women; they thus organized in separate unions, not from choice but from necessity.

These formal kinds of discrimination and informal cultural attitudes were closely connected so a young woman who was politically active was likely to gain a reputation as a virago. In Florence’s words, I was known locally as a she-devil’.

It was not really surprising that when Annie Kenney, a former Lancashire mill worker, became a full-time organizer for Mrs Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union in the South of England that this ‘she-devil’ should gravitate towards the suffragettes. The WSPU had initially come out of the Independent Labour Party, and in 1908 still had quite close links with supporters in the socialist movement. Locally too the London controversies were less important, and in Southampton there appears to have been interaction between the WSPU and women like Florence involved in other forms of radical activity. There were also links to the larger more sedate, suffragist group, the Women’s Suffrage Society.

While the Southampton Women’s Social and Political Union was a small group, it was very active and an enthusiastic Florence, still in her teens, ‘ spent many early morning hours chalking the pavements of Southampton with slogans such as ‘Votes for Women’, until the local council passed bye-laws prohibiting it. She also ‘did much fly-posting at night’ and ‘bill-delivering’, helping to organize indoor and outdoor meetings. ‘Most meetings were the butt of students who threw stones, eggs or tomatoes, and many an indoor meeting had to be abandoned because of floating pepper thrown by the opposition’.

She acted as press secretary – a thankless task because the newspapers would not give the suffragettes publicity in case it brought them more supporters. Instead they created their own methods of propaganda, ‘The most nerve-wracking experience was going round the streets ringing a bell and shouting through a loud hailer about the meetings’.

In June 1908 the Women’s Social and Political Union held their first major demonstration in London. Thousands and thousands of people, men as well as women, converged on Hyde Park, demanding ‘Votes for Women’. The WSPU had organized cheap rail tickets for the occasion and sections marched from every railway terminal. Seventeen year old Florence carried the Southampton banner with great pride from Waterloo. ‘Because of my pigtails the police accompanying the march were highly amused.’

From 1909 the WSPU, exasperated by the Liberal government’s lack of response, were attacking property and thus risking arrest. In 1910 the Extens moved to Bristol. Florence was still a member of the WSPU but over the next few years as militancy escalated, said she was ‘ceasing to be active for I disapproved of the altered strategy so fundamentally that I broke away at last’. Florence believed it was more effective to struggle within organizations legally. By 1911 -12 Florence was joining various bodies which she hoped could ‘by pressure help the women’s movement’ – the socialists used similar tactics.

Despite breaking with the WSPU, her politics ‘continued to be governed by the interests of girls and women’. While still a member she had become aware of the low pay of the Cradley chainmakers and the exploitation of home and sweated workers which was being exposed by the Anti-Sweating League.

Her own experience from 1911 as a clerk in a Bristol brush factory confirmed a consciousness of injustice. Florence observed, ‘In 1911, I earned 8 shillings per week at what was grandiloquently described as a “departmental section clerk”. ‘

This was little enough, but it meant she was a veritable aristocrat when compared to the manual workers in the brush factory who were on piece work. ‘In this brush factory girls made miners’ lamp brushes for ½ d (a half penny in old money)…. To make these brushes women had to sit around some boiling pitch, tie a very small bunch of bristles and dip it in the pitch, then push it in the stock.’ She commented how if the stock broke before it was finished, even if it were almost complete, they received no pay.

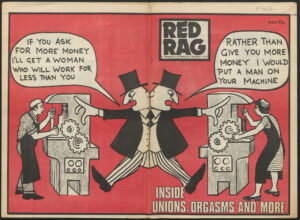

Florence was active in the Bristol trade union movement, speaking in 1911 at the Shop Workers’ Conference. Though critical of ideas of separate women’s unions on the grounds that this treated women as a separate class, she derided prejudice in the mixed trade union movement. ‘The differences between man’s work and woman’s is no more than a cherished trade union phantom. This was proved during the two world wars’. She reflected too on the attitudes of employers, ‘…one found that a woman is required to be more experienced and better equipped than a man in order to obtain a post; then to work harder and obtain twenty-five per cent less salary.’

She was a trade unionist because of her feelings of class and gender injustice, but the meetings in Bristol acquired an added attraction when she met a young grocer’s assistant, Maurice Hann who had been elected several times on to the executive. ‘I did all my courting in trade union meetings’, she chuckled. Like Florence, Maurice was a member of the Independent Labour Party. A prominent fellow ILPer, Katharine Glasier, used to call them ‘the doves’ because of this trade union courtship.

Political trouble came for Florence when ILP women in Bristol formed a Women’s Improvement Society to encourage women to come to discussion classes and hear speakers. ‘I got into hot water for telling the women off for knitting. I thought it was rude’. The other members took offence and said ‘they weren’t going to be dominated by such kids as Miss Exten’.

She and Maurice were aware that some anarchists and socialists were rejecting marriage as an institution and choosing to live in free unions on principle in defiance of the prevailing attitudes. They discussed this, but decided to marry in 1913, the year that Maurice got a job as Organizer in the union.

During the First World War they were living in London and active as members of the Islington ILP. Florence became a pacifist – she was sympathetic to the Quakers. The war divided the suffrage and the socialist movements including the ILP. Christabel and Emmeline Pankhurst became fiercely patriotic and both suffragettes and suffragists supported the war effort. Others, including Sylvia Pankhurst were opposed, some like Sylvia, because they regarded it as a capitalist war, others like Florence on moral grounds.

The peace movement was not strong enough to dwell on internal differences for they faced overwhelming opposition and often had to work in secrecy. Pacifists and revolutionaries were thrown together. Florence met Sylvia through the peace movement and liked her but thought she was always hampered politically ‘..by her artistic temperament which wouldn’t allow her to be calm’. She was less keen on Emmeline, ‘her mother was more or less a sergeant major’.

Lilla and Fenner Brockway initiated the No Conscription Fellowship to bring anti –war protesters together and Florence became the NCF official organizer for the southern and eastern regions. She worked for a very low wage, travelling around the country visiting conscientious objectors in prison and army camps. Her involvement in the NCF was not illegal but because the wartime state was apt not to make fine distinctions the biscuit tin containing the names and addresses of supporters was buried securely in Florence and Maurice’s garden.

In 1918 the biscuit tin was dug up because it was thought that the danger of a police raid was over. But the police did raid and found the tin which had been left in the bathroom. Presumably it was politically useful for them in the insurrectionary atmosphere of 1918 -19 to have the names of members who had had the courage to resist the war.

Florence continued to support the peace movement and retained her interest in trades unionism. She took pride in being able to contribute towards the upkeep of her and Maurice’s home, working first for the League of Nations Society and afterwards for the Marlborough Street Employment Exchange for Women and then for the Municipal Journal.

In the last twenty years of her life she was involved in the Stanmore Workers’ Education Association, developing an interest in archeology and medieval history. She did a lot of voluntary clerical work for the WEA branch and was often to be found knitting for someone’s baby.

I taught a daytime class for the WEA in Stanmore in 1973 and my students sent me to see Florence and Maurice because I was a socialist feminist. Florence was a little wary when I first turned up in March that year because she had heard strange tales of bra burning ‘women’s libbers’ as we were called in the press. She was relieved, if somewhat surprised, to discover we too supported trades unions.

She was 82 when I visited; her thick, unruly white hair parted in the middle framed an alert, mobile face – her eyes full of empathy, warmth and curiosity. She told me that she did meet regularly with old friends at the vegetarian restaurant, Cranks near Tottenham Court Road, but was apologetic because she did not feel energetic enough to become active in the women’s liberation movement. I reassured her. I was simply so happy to connect with a fellow spirit more than fifty years my senior.

I was only just in time – Florence died shortly afterwards.

I visited Maurice the following July. In his early nineties, dapper in his brown knitted waistcoat, he took a mischievous delight in engaging me in arguments about workers control. He relived his dismay when socialists split over the war in 1914. ‘If you want to keep your illusions about left politics’ he warned sardonically, ‘make sure you never get close to the centre of any organization’.

As I was leaving he handed me some of Florence’s Clarion pamphlets and a book , Mary Higgs and Edward H. Hayward, Where Shall She Live: The Homelessness of the Woman Worker, published by the National Association for Women’s Lodging-Houses in 1910. He also gave me a Clarion card inscribed with the words ‘Bread and Butter – and Roses’.

Thanks to the internet I have now discovered that in 1934 G. Maurice Hann chaired the committee for a great Labour Peageant organized by the Central Women’s Organization Committee to the London Trades Council- unfortunately it lost money. In 1936 he is mentioned as being a staunch defender of Republican Spain and he served as General Secretary of the Shopworkers’ Union 1936-46.

Lilian Wolfe: She Lived Her Politics

Born in 1875, Lilian Gertrude Woolf (later Wolfe) was involved first in the suffrage and then in the anarchist and anti-war movements. She died in 1974.

I met Lilian Wolfe for the first time on September 9th, 1973 at the Rudolf Rocker Centenary Celebration at Toynbee Hall, Whitechapel. The name of the East End anarchist who organized the Jewish clothing workers had become well known to me through my friendship with William Fishman, anarchist historian and the principal of Tower Hamlets College of Education, where I had taught during the 1960s. By 1973 I had also met the anarchist writer Nicholas Walter.

I went to interview her a few weeks later at the War Resisters’ International in Kings Cross where she was busy stuffing copies of Peace News into envelopes. She explained her very impressive filing system to me and fed me on vegetarian food from the Cotswold community, Whiteway, near Stroud, Gloucesteshire while we talked.

Lilian Wolfe’s father Albert Lewis Woolf was a Jewish jeweller and politically conservative; her mother Lucy Helen Jones, had been an actress who left the family when Lilian was thirteen to join a touring opera company, leaving Lilian and her three brothers and two sisters, ‘to think and do as we liked’.

Her eldest brother paid for her to train as a telegraphist at the Regent Street Polytechnic and Lilian went to work as a telegraphist at the Central Office (GPO) in London and ‘hated every minute of it’. She had already drifted towards socialism without remembering quite how – ‘I found myself thinking that way’. Her younger brother was also interested in socialism and so was one of her friends, Mabel Hope, who was also at the GPO Central Office and the Telegraph Department of the Civil Service. Through her work Lilian joined the Civil Service Socialist Society.

She was initially shocked when she first heard of the suffragettes’ militant tactics, ‘I thought it was terrible the way they were acting’. Then her supervisor in the Civil Service took her to a meeting and they explained they used tactics like burning letter-boxes in order to make it impossible to ignore them. But she found the leaders, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst too arbitrary and authoritarian and joined the Women’s Freedom League, a breakaway from the Pankhursts’ Women’s Social and Political Union. Formed in 1907, the Women’s Freedom League adopted non-violent direct action. There was considerable hostility to supporters of women’s suffrage regardless of their tactics. Once while speaking on women’s suffrage with a friend in Salisbury market place Lilian remembered how they were pelted with cabbages by hostile onlookers.

There was a strong current within the left before World War One which rejected working for reforms through Parliament and believed in direct action. The suffragettes were in a curious half-way position. They were using militant direct action to influence Parliament. Lilian began to feel increasingly that all the effort to persuade politicians to change their minds was misplaced, and along with Mabel Hope, she began to move towards anarchism and direct action ideas.

In 1913 she and Mabel Hope joined the Anarchist Educational League. This had been started by Fred Dunn, who worked for the Post Office in a sorting office and whose father had been a founding member of the Social Democratic Federation. When they thought of restarting an anarchist paper directed at workers, Voice of Labour, it seems to have been Mabel Hope who introduced them to Tom Keell, the compositor and editor of the anarchist paper Freedom,.

Lilian recalled her first encounter with him. ‘When we were going to start the Voice of Labour we held a meeting to know how we should go about it. We had no experience’. Tom Keell came along with what Lilian described as ‘a watching brief’. After they had talked in circles for some time he stood up and explained clearly how they could get started. Lilian was indignant at his silence and the time wasted and demanded, ‘Why couldn’t that man have spoken before?’

‘That man’ was to become her companion for many years. An extremely skilled compositor, Tom was renowned for his ability to set type at the same time as having a spirited debate. Lilian remembered him with affection and pride. ‘We got friendly and eventually fixed up together. He was the nicest man I ever met. The sort of man you could discuss anything with’. She said the years they spent together were the happiest in her life.

The Voice of Labour reappeared in 1914, edited by Fred Dunn, helped by Lilian’s organizational efficiency. ‘I did the hack work’, she told me. It was a weekly, becoming a monthly when the First World War began. It strongly opposed the war.

Tom Keell as editor of Freedom was confronted by a dilemma, for Peter Kropotkin, who had been associated with Freedom since the nineteenth century and was a loved and revered figure in the anarchist movement, argued that they should side with the allies. Tom Keell himself was opposed to this and published a reply by the anarchist thinker Errico Malatesta contesting Kropotkin’s position. The painful split became bitter but Tom Keell was supported by the Voice of Labour group Lilian, Fred Dunn, Mabel Hope and her friend Elizabeth Archer. In March 1915 Freedom published a passionate anti -war statement, the ‘International Anarchist Manifesto on the War’, which appeared later in several anarchist publications in Europe and the US. Among the signatories, which included Malatesta, Alexander Berkman, Emma Goldman and the Christian pacifist F. Domela Nieuwenhuis were Fred Dunn, Tom Keell and Lilian G. Woolf.

Lilian told me how early in 1915 an anarchist community was started at 1 Mecklenburgh Street, off Bloomsbury Road, London. Domestic work was divided by the people who lived there who included Lilian and Tom. They held meetings and socials every Saturday night to raise money for Freedom and the Voice of Labour. They had a piano and Lilian described how youngsters from Rudolf Rocker’s anarchist group in the East End used to come and dance. Imagining wild ragtime, I enquired what kind of dances? Lilian replied that it was waltzes mainly, adding ,’ The older ones used to come and talk and talk’.

When I asked Lilian about anarchist groups in this period, she did not remember any actual groups apart from the East Enders and one group in Stockport. She recalled individual people just being around rather than specific groupings. I have often puzzled away at this and wished I had questioned her more deeply.

East End anarchists of course had a long tradition and strong international links. The Stockport group she mentions met at the Communist Club in Park Street, Hazel Grove. They were not isolated for they had been in contact with sympathisers in the locality who helped them to establish the Club. They also had links with other Workers’ Freedom Groups which inclined to anarchist communism and existed elsewhere (including in Bristol). Anarchists held conferences at the Stockport Communist Club’s premises and Fred Dunn uses the term ‘The Movement’ to describe the congress which gathered at the Club in April 1915 to oppose the war. This was probably how Lilian knew of the Stockport group.

Alongside the conferences, publications and manifestos, networks among anarchists were also formed through friendships and personal love affairs. These could be profoundly important. I think this might be why Lilian recalled individuals being just around. For example, there is a 1915 photograph of Lilian at the anarchist holiday camp at Harlech with Fred Dunn, Emily Wilkinson who taught Morse code in the Post Office, her brother George Wilkinson and Bert Wells. (https://libcom.org/history/dunn-fred-1884-1925)

Ken Weller in his 1985 book of Don’t be a Soldier traces how rebel networks formed among those who were opposing the war in North London in which anarchists, socialists and pacifists combined. Amid the repressive circumstances of the war personal friendship networks also overlapped, connecting anarchists, pacifists and socialists. Several Stockport anarchists who were imprisoned with Fenner Brockway for opposing the war joined him in resisting the prison regime.

The intelligence agents, many of whom were recruited from the armed forces and accustomed to rigid command structures, struggled to establish leaders amongst those they were pursuing and tied themselves in knots trying to work out links between opponents of the war. Subsequently historians too have faced problems detecting interactions and groupings in informal organizational networks, especially of course those that were necessarily operating in secret. Buried beneath the No Conscription Fellowship, there were shadowy networks helping men to escape to the US. But numbers and names are obviously difficult to trace.

But despite flexibility and fluidity in how the movement against the war can be construed, there were also differences in emphases and tactics. Lilian helped to start the uncompromising anarchist No Conscription League which called on workers to refuse call-up.

After the Military Service Act in January 1916 such absolute resistance was extremely dangerous. When Fred Dunn defied being drafted, he was arrested, put in a military prison and sent to a regiment, but managed to flee to the Scottish Highlands. On the run along with George Wilkinson and Bert Wells, he contributed an article called ‘Defying the Act’ by ‘one of those outlawed to the Scottish hills’ to the April 1916 issue of Voice of Labour. Nevertheless, no doubt through the anti -war networks, he managed to flee to the United States where he taught at the libertarian Modern School which adopted the educational ideas of Francisco Ferrer.

By May, however, most of the other men in hiding in the Highlands had been arrested. Tom Keell printed 10,000 copies of the article as a leaflet and Lilian with her customary efficiency distributed them, even though when the article was being written she had urged restraint. Copies, including one to Malatesta, were intercepted by the police, the Freedom Press offices were searched and she and Tom were arrested and tried in June under the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) for ‘conduct prejudicial to recruiting and discipline’. Tom pleaded not guilty and Lilian guilty. He was fined £100 and she was fined £25. When they refused to pay, Tom got three months for printing the leaflet and Lilian was sentenced to two months. Mabel Hope took over editing The Voice of Labour but had to stop in August 1916. She and Elizabeth Archer later went to America.

Lilian was pregnant in the summer of 1916 so she spent her sentence in Holloway prison hospital, to the bewilderment of the prison doctor who appeared never to have ‘had to deal with a pregnant woman before. He seemed very confused.’ Her vegetarianism caused more confusion; she begged to be given the ‘water the cabbages were boiled in’ because she was afraid that the prison diet would be harmful to the baby she was carrying. She was allowed one precious apple a day, saving it until the evening as a treat.

Psychologically the prison affected her very badly though she was not physically ill-treated. ‘I thought I was going mad. My head was going round and round. But the only person nasty to me was the clergyman – he shouted at me that I was German. So I lived for some months in terror that they would repatriate me.’

She paid her fine two weeks before she was to be released because she was afraid for her child’s safety. She had already resigned from the Civil Service and from the work she had always hated before being imprisoned. I wasn’t going to wait until they chucked me out’. She applied to go into Queen Charlotte’s Hospital to have her baby, but they refused her, not because she wasn’t married but because she was an unrepentant sinner who intended to live with the baby’s father afterwards. ‘I certainly was one of the first single women to have a baby deliberately’. Her son was born when she was 41 years old and she called him Tom after his father.

Although free unions were being discussed by people on the left, it took considerable courage to act on your principles. This was particularly difficult for women because the double sexual standard meant they were always more vulnerable to moral censure than men. Lilian said the decision to have a child came from her anarchist rejection of the authority of the state rather than from feminism. When I asked her about feminism she said she had not really been interested in it though her friend Mabel Hope was. (Mabel Hope had campaigned for women’s rights at work and spoken at both Labour Party and Social Democratic Federation meetings before writing for Freedom and editing Voice of Labour. )

After becoming a mother Lilian did not become economically dependent on Tom. Indeed, quite the reverse; she worked to keep Tom, young Tom and Freedom going by running health food stores in London and then in Gloucestershire. Friends like Emily Wilkinson were at the Whiteway Colony and Lilian and the two Toms lived there in the 1920s and 30s.

Whiteway, a self- governing community formed upon Tolstoyan principles, adopted the Quaker custom of decision –making by general agreement until conflict between anarchists and marxists made voting necessary. Sylvia Pankhurst came to stay for a short time and Lilian got to like and admire her while retaining her old animosity to Emmeline and Christabel who had moved to the right.

Tom died in 1938. Lilian continued to run a health food shop in Stroud through the Second World War, despite queues and ration cards. After Freedom folded in the 1930s a new group of anarchists emerged including Vernon Richards and Marie Louise Berneri. In 1943 Lilian went to London to work with them on War Commentary. Once again the intelligence service were keeping tabs on them. A raid in December 1944 was followed by arrests in 1945 amidst protests from, among others, Fenner Brockway.

Lilian’s political activism continued in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, (CND) and she went on the Aldermaston march from 1958 onwards. The non-violent direct action of Committee of 100 brought socialists, pacifists and anarchists together once more and contributed to a critical approach to the state which influenced the new left. Between 1961 and 1964 Lilian sat down with Committee of 100 and was arrested and fined yet again.

This was the period in which I became aware of new left ideas as a student and, through friends active in CND and Committee of 100, read Kropotkin as well as Marx. I discovered Colin Ward’s magazine Anarchy published by Freedom Press before meeting William Fishman in East London and winding my way down the Whitechapel alley to the revived version of Freedom. I was unaware then that Freedom had sent a truly extraordinary anarchist woman off for a holiday in America to celebrate her ninetieth birthday. Lilian experienced her first ever aeroplane flight and reconnected with many old friends.

By the time I met Lilian Wolfe she was in her late nineties. This great encourager and helper had carried on working without expecting any recognition, saving money from her pension to give to anarchist papers, political prisoners and other radical causes. She still remained open to new movements and ideas. Though she did not agree with 1970s feminism, she was pleased when Sandy Martin’s article appeared in the Stratford Women’s Liberation group issue of Shrew and she was quoted in my Hidden from History (1973). She did not seem to mind that I was not an anarchist, but was distressed to find I was not a vegetarian and shook her head when I said I didn’t like cheese.

Feminist or not, I certainly detected more than a twinkle when she described how she did the ‘hack work’ on Voice of Labour and I responded by commenting on how a lot of women on the left who went into women’s liberation when it started had found themselves in the same position.

I felt a very close affinity with her brave commitment to living her politics because that was what many of us who were socialist feminists in the early 1970s were also struggling to do. But that’s another story.

I left her in September 1973, frail, tiny and determined, mounting a bus to go to the Chinese exhibition of archeological finds at the Royal Academy, chuckling about how she could get to the front of the queue as a pensioner. We corresponded for some time after that and then I heard that she had died in April 1974, aged 98.