Warning – Due to the nature of the topic this article is not suitable for children

The stench of the hold…was so intolerably loathsome that it was dangerous to remain there for any time…but now that the whole ship’s cargo were confined together, it became absolutely pestilential.[1]

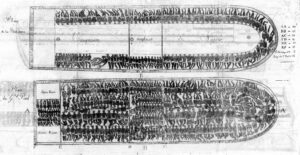

Let me begin by saying that there was nothing unique about the utterly appalling conditions that existed on the Hannibal slave ship: All merchant slave ships were floating prisons of cruelty and depravity. For the enslaved Africans on board a slave ship sailing to the New World – in this case Barbados – they were to experience a passage of unimaginable horror. The 372 enslaved Africans who survived the voyage on the Hannibal spent a total of 126 days onboard the ship after it had departed Whydah. (Now known as Ouidah in the Republic of Benin, West Africa). The enslaved men were chained in irons within the hold of the ship on what were known as ‘the slave decks’. Graphic image No.1 depicts how the captive men on the lower were to be shackled and positioned below deck. The men were allowed onto the upper deck to have their food and water twice a day unless there was fear of an uprising occurring. Captain Thomas Phillips referred to the slave decks as ‘kennels’.

being all upon deck…till they have done and gone down to their kennels between decks…[2]

A chilling document has survived, dated 8th September 1693, with Phillips requesting that the mast-makers of Deptford and Woolwich be ordered to work faster in fitting new platforms and that the blacksmiths to have the same orders for fitting ironwork. In the below letter that Phillips wrote on 8th September 1693 from St James, Deptford, London, he refers to the urgent need for carpenters and blacksmiths to fit secure slave decks in the hold of the Hannibal:

…the favour that you be pleased to order the Mast Builders both of Deptford and Woolwich…to fit the platforms and the other conveniences of the bombress [prison?) within board in the hold and that the Smiths … have the same Orders to and such Iron work as be needful for the security of the platforms [iron rings and chains]…and that the men which are intended for them be ordered as soon as possible…[3]

The Hannibal’s refit was at considerable expense and had to incorporate extra decks to carry seven hundred enslaved Africans. Her quarter-deck guns were repositioned to be directed onto the hatchway leading down to the hold of the ship where the enslaved were to be shackled below decks.

The slave decks were a living nightmare. To slave traders, enslaved human beings were simply considered cargo, and slave ships were particularly designed to transport as many captives as possible. Little to no regard for either their health or comfort was incorporated into the design despite the people being a valuable commodity. Although for monetary purposes the enslaved people were considered as cargo, some of the captives would have been trained warriors, and therefore more than capable of plotting to take over the ship. Essentially there was always fear among the crew of a slave uprising occurring particularly when still close to the African shore. Phillips wrote of the extensive precautions he took to prevent the enslaved taking over his ship.

When our slaves are aboard we shackle the men two and two, while we lie in port, and in sight of their own country, for tis then they attempt to make their escape, and mutiny; to prevent which we always keep centinels upon the hatch ways, and have a chest of small arms, ready loaden and primed, together with some granada shells [grenades]; and two of our quarter-deck guns, pointing on the deck thence, and two more out of the steerage, the door of which is always kept shut, and well barred…they are fed twice a day which is the time they are attempt to mutiny,…[4]

Phillips wrote of his feelings about how to punish potential ringleaders:

I have been informed that some commanders have cut off the legs or arms of the most wilful, to terrify the rest, for they believe if they lose a member, they cannot return home again: I was advised by some of my officers to do the same, but I could not be persuaded to entertain the least thoughts of it, much less to put in practice such barbarity and cruelty to poor creatures, who, excepting their want of Christianity and true religion, (their misfortune more than fault)…[5]

If nothing else the above points out that the Hannibal officers onboard were capable of carrying out tremendous cruelty and doubtless other not so brutal punishments were probably carried out on any person they suspected of not being a passive captive. Rarely one such incident was recorded in writing during July 1748. Captain Richard Jackson of the Brownlow slave ship had foiled a failed insurrection of his slaves on board. He ordered the punishment of the most rebellious slaves to be of a most savage and nauseating penalty possible; to die by cutting off each limb below one joint at a time, finishing with the head, and then throwing the body parts among the slaves grouped and chained on the deck as a warning.[6]

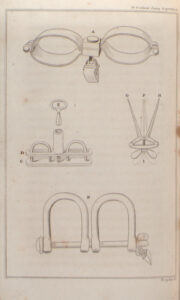

All slave ships carried instruments of torture. Common punishments to subjugate the enslaved were public whippings, torture with thumb screws, rape, and the speculum oris, a device used to enable forced feeding. (See image No.2). Slave trade captains were carefully selected for their business acumen and temperament in the pursuit of profit. If they proved to be tyrannical sadists or psychopaths, this would not be an issue, so long as their voyage proved profitable, without too high a loss of enslaved African lives: How this profit was achieved would not be in question at this time.

Slave decks were often only a few feet high, and the African captives were locked together in iron chains while lying down, side by side, sometimes head to foot.[7] Although the enslaved Africans were a valuable commodity, death from suffocation by over-heating, dehydration, malnutrition, scurvy, suicide, and a variety of infectious diseases were extremely common. These maladies occurred to a greater or lesser extent on all slave ships. The men would acquire sores from their forced positioning on rough wood-planked decks. Some captives also developed leg ulcers from the rubbing of the heavy crude chains laying around their ankles and across their shins making movement very painful. The jettisoning, or throwing, of the dead and dying overboard to prevent the spread of disease, and thereby to protect profits, was a daily occurrence on the Hannibal. To a man like Phillips each time a person died he only ruminated on the fact he had just thrown £20 over board.[8] Such horrors were sometimes recorded in the journals of ships’ surgeons and by a very few captains: Phillips made no mention of how the dead and dying were treated onboard his ship.

The Women

The women were allowed more freedom onboard but it can be presumed that the women were also confined below decks for some of the Hannibal voyage based on the records of other slavers. For example. at times of slave unrest and suspicion of an uprising being plotted, the women would have also been chained and confined below.

Image No.1 depicting the upper slave deck c.1814 provides an illustrated layout of the women’s slave deck which was positioned above the men’s deck. In this plan a woman giving birth is illustrated to suggest the space allocated to the women for this purpose: The representation serves to demonstrate that for enslaved women their true value was her womb – to provide further enslaved people at no extra outlay for plantation owners. It is not known if any children were born on the Hannibal, but it is reasonable to suggest that miscarriages would have occurred due to the horrific circumstances inflicted by captivity. Three percent of the captives onboard the Hannibal were children, and, as far as is known, the children generally had the run of the ship and were not restrained or confined below decks.

Enslaved African women commonly experienced sexual exploitation while onboard a slave ship. Some officers and their crew believed the old racist European myth that Black women, born in Africa, were sexually promiscuous. For advocates of this myth it served a purpose; Black women could not be raped because they were sexually uninhibited.[9] Torture by rape upon the enslaved women was common place, and although there is no mention of such acts being carried out by the crew of the Hannibal, it is extremely unlikely that any captain would record sexual abuse occurring on his ship. Some plantation owners complained several months after purchasing enslaved African women that many were found to be in the early stages of pregnancy, giving birth to mixed race babies on the plantation.[10]

Alexander Falconbridge wrote of the strains of ship-board life for the enslaved; disorientation, disease, loss of family and children, and punishment. Deprivation and depravity took a severe toll on the enslaved captives and many became ‘raving mad’ and died thus, ‘particularly the women’.[11]

Phillips writes extraordinarily little about the treatment of the enslaved women on his ship, but he does mention their segregation from the male slaves.

The men are all fed upon the main deck and forecastle, that we may have them all under command of our arms from the quarter-deck, in case of any disturbance; the women eat upon the quarter-deck with us, and the boys and girls upon the poop; after they are once divided into messes, and appointed their places, they will readily run there in good order of themselves afterwards.[12]

John Newton, a former sailor, mate, and eventually captain of a slaver who turned abolitionist later wrote in life and when giving evidence to parliament:

…perhaps no part of the distress affects a feeling more, than the treatment to which the women are exposed. But the enormities frequently committed, in an African ship, though equally flagrant, are little known here, and are considered, there, only as matters of course. When the Women and Girls are taken on board a ship, naked, trembling, terrified, perhaps exhausted with cold, fatigue, and hunger, they are often exposed to the wanton rudeness of white Savages. The poor creatures cannot understand the language they hear, but the looks and manner of the speakers, are sufficiently intelligible. In imagination, the prey is divided, upon the spot and only reserved till opportunity offers. Where resistance, or refusal, would be utterly in vain, even the solicitation of consent is seldom thought of. But I forbear. —This is not a subject for declamation. Facts like these, so certain, and so numerous, speak for themselves. Surely, if the advocates for the Slave Trade attempt to plead for it, before the Wives and Daughters of our happy land, or before those who have Wives or Daughters of their own, they must lose their cause.

…[some would say] that the African “Women are Negroes, Savages, who have no idea of the nicer sensations which obtain among civilized people”. I dare contradict them in the strongest terms. I have lived long, and conversed much, amongst these supposed Savages. I have often slept in their towns, in a house filled with goods for trade, with no person in the house but myself, and with no other door than a mat [very safely, without locks as we require in this country]… I have seen many instances of modesty, and even delicacy which would not disgrace an English woman.[13]

Marcus Rediker states that slave trade merchants downplayed the rumours of rape and stressed that ‘good order’ onboard slave ships ensured that no abuse of female slaves occurred by the crew.[14] A parliamentary investigating committee during 1789 enquired of a Captain Robert Norris, ‘Is that any care taken to prevent any intercourse between white men and black women?’ to which Norris responded, ‘orders are generally issued for that purpose by the commanding officer.’ ‘If a British sailor should offer violence to a negro woman, would he not be severely punished by the captain?’. Norris answered, ‘he would be sharply reproved certainly.’ ‘It would be written in a sailor’s contract that if any sailor proved guilty of a vice while on the voyage, he would lose one month’s pay.’[15] However, how exactly ‘good order’ was to be interpreted was at the discretion of the captain.

Phillips gives us only a few passages in his journal where he considers the plight of his enslaved captives. He admits that he was holding the people in dreadful conditions, but he did nothing to alleviate their suffering. He only recorded that he ordered the slave decks to be kept as clean and sweet smelling as possible. This however was not out of pity but only to prevent disease and death in order to preserve the profits obtained from freighting charges the sale of his captives on arrival in Barbados.

The journal does offer a few paragraphs to describes how the enslaved spent their days and nights such as meal times and exercise in relation to demonstrate Phillips was following his orders laid down by his employers, the Royal African Company. He also describes the enslaved as if neglected animals, saying they were ‘making a stink’ when referring to the captives as they came down one by one with dysentery. Incredibly, as if it were of their own making. Phillips bemoans that he and the crew had to ‘endure twice the misery’ of the enslaved, even declaring that it was all for ‘so little purpose’, meaning for so little profit. These assertions written by Phillips are very telling about his personality.

The enslaved Africans were ordered to dance under the threat of the whip. (A forced form of exercise).

We often at sea in the evenings would let the slaves come up into the sun to air themselves, and make them jump and dance for an hour or two to our bag-pipes, harp, and fiddle, by which exercise to preserve them in health…[16]

Phillips was much in agreement with a Dutch slaver he met while on shore at the island of St Thomas off the central west African coast during 1694. Captain Clause told Phillips he was carrying 200 enslaved Africans, and he disclosed in conversation with Phillips that he was also experiencing much sickness and death on his ship. According to Phillips, the Dutch captain was full of resentment, saying of the enslaved Africans, ‘with their stink and nastiness … if he lived to return to Holland, he would deliver them [the ship owners] his ship’. And that if they were to pay him £100 a month he would refuse it, ‘preferring to become a common sailor for 20 guilders a month.’[17]

Phillips gives no mention of punishments metered out to the enslaved by his crew but he did write about the African overseers (who were themselves enslaved) who were given the whips known as cat of nine tails.

… and sleep among them to keep them from quarrelling; and in order, as well as to give us notice, if they can discover any caballing or plotting among them, which trust they will discharge with great diligence…when we constitute a guardian, we give him a cat of nine tails as a badge of his office, which he is not a little proud of, and will exercise with great authority.[18]

Phillips was selected to command a slave ship by men already entirely acquainted with the horrors of the trade which suggests that he was considered brutal enough to command and keep discipline over 700 enslaved Africans. The Infliction of physical and psychological atrocities during the transatlantic slave trade period was accepted practice to many during an era when slavery was a state sanctioned legal activity.

Out of a total of the 700 enslaved people, forcibly transported on the Hannibal, only 372 survived the passage from west Africa to Barbados. This was an unusually high death toll being a mortality rate of nearly 50 percent. Records indicate that during the seventeenth century, the average mortality rate for any given slave ship making the passage from Africa to the Americas was between five and about twenty percent. The surviving enslaved people carried on the Hannibal, their children, and their children’s children, were to spend their lives toiling in back breaking labour on plantations during the next 140 years of the continuing transatlantic slave trade. This is a history of a great tragedy known for its exploitation of people at extreme levels, and in enormous numbers, being estimated to be above 12 million over 400 years. These are the forgotten people in Phillips’s journal. We can never be seen to defend or ignore the great suffering caused by the inhumane treatment inflicted upon others by the hands of men like Captain Thomas Phillips.

[1] Equiano, Olaudah. ‘The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, the African’. 1792. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/15399/15399-h/15399-h.htm

[2] Phillips, Thomas. A Journal of a Voyage made in the Hannibal of London, Ann. 1693, 1694, From England to Cape Monseradoe, in Africa, and thence along the Coast of Guiney to Whidaw, the Island of St. Thomas, and so forward to Barbadoes. With a Cursory Account of the Country, the People, their Manners, Forts, Trade, etc. within a Collection of Voyages and Travels. Churchill. 1732. Vol.VI. Churchill. p.229. Hereafter referred to as Journal.

[3] TNA. ADM 106/437/239

[4] Journal p.229

[5] Journal p.219

[6] Rediker, Marcus. The Slave ship: A Human History. Viking 2008. p.218

[7] For example, the Brookes (c.1801) slave ship slave-decks were only 10 inches high. British Library. Learning Times: Sources from History. Sourced. 14 Feb.2023

[8] 1694 in £20 = RPI £3,000 in 2022

[9] Donovan, Ken. Female Slaves as Sexual Victims in Île Royale. Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region. Vol.43. No.1. 2014. pp.147–56

[10] Bush, Barbara. Daughters of injr’d Africk’: African women and the transatlantic slave trade. Women’s History Review. Vol.17. No.5. pp.673-698

[11] Falconbridge, Alexander. An Account of the Slave trade on the Coast of Africa. In Bush, Barbara. ‘African Caribbean Slave Mothers and Children: Traumas of Dislocation and Enslavement Across the Atlantic World.’ Caribbean Quarterly. Vol.56 Is.1/2. 2010. pp.69-94

[12] Journal p.228

[13] Newton, John. Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade. 1788. Para no.8

[14] Rediker. The Slave Ship. A Human Story. p.242

[15] Robert, Norris. A Short Account of the African Slave Trade. 1789, and HCSP, 68:9, 12. In Rediker. p.243

[16] Journal p.230

[17] Journal p.228

[18] Journal p.230