There’s a wave of interest in open-air swimming right now. Campaigners in Bristol recently led demands for wider access to swim in our rivers, lakes and even the Floating Harbour. It’s a leisure activity first popularised in the city three centuries ago by a maverick businessman, who built one of Britain’s earliest public swimming pools. Peter Cullimore, a retired journalist turned local historian, has been investigating the story of Rennison’s Baths.

Introduction

Buried under a GP surgery in Bristol lies an extraordinary piece of social history. Montpelier Health Centre is a spacious modern building, providing healthcare for a diverse community, a mile or so from the city centre. What scarcely any of its patients, or even staff, realise is that where they tread today, for hundreds of years people swam.

One weekend while the surgery was closed, an obliging doctor gave me access to an area outside at the back. It’s a rather scruffy paved garden, enclosed on three sides by high walls of stone and brick. The garden is normally unseen by the public. However, still visible are traces of an open-air swimming pool, dating from the mid 18th century. The much-repaired walls are original and surrounded a lido known as Rennison’s Baths. You can make out one corner of the main pool not entirely covered up by the health centre. There are still steps where swimmers descended into the water. Next to them, a section of blue and red tiles from the sides of the pool also remain in place.

One weekend while the surgery was closed, an obliging doctor gave me access to an area outside at the back. It’s a rather scruffy paved garden, enclosed on three sides by high walls of stone and brick. The garden is normally unseen by the public. However, still visible are traces of an open-air swimming pool, dating from the mid 18th century. The much-repaired walls are original and surrounded a lido known as Rennison’s Baths. You can make out one corner of the main pool not entirely covered up by the health centre. There are still steps where swimmers descended into the water. Next to them, a section of blue and red tiles from the sides of the pool also remain in place.

This was one of the earliest public swimming pools in Britain. The complex included a separate pool for women only. It was built by the owner Thomas Rennison, a businessman from the West Midlands, for the local community to swim and frolic in. Next door stood a tavern, popular with the bathers. Rennison called his pub the Old England, and it’s still there.

The Rennison name was well known in Bristol from the Georgian era right up to the First World War, when Rennison’s Baths finally closed for good. Despite attracting tens of thousands of customers a year, the family business accumulated a mountain of debt, from reckless borrowing by Thomas and relatives. His namesake son and grandson inherited the chaos. During the 19th century, swimmers complained about filthy water in the main pool. Yet somehow, the Rennisons always stayed afloat.

Thomas Rennison (1707-1792) was a bold and flamboyant entrepreneur, originally from rural Derbyshire. He had a gift for self-publicity but also a tendency to spend other people’s money and embroider the truth. He built up large debts as a thread maker in Birmingham and was declared bankrupt in 1742, probably moving to Bristol around this time. One contemporary list of bankrupts gave his address as ‘late of Birmingham’.[1]

Pleasure baths

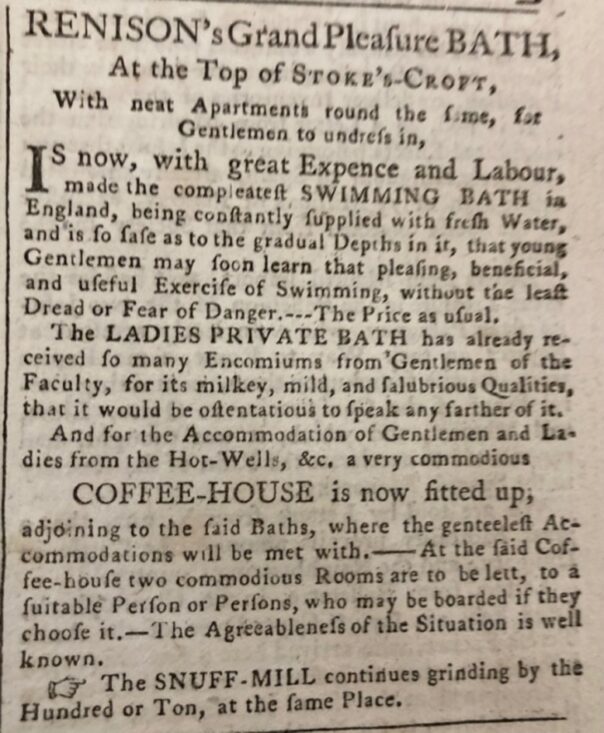

We shall examine later why Rennison changed his career focus from spinning to swimming. However, a newspaper advertisement for ‘Rennison’s Grand Pleasure Bath’, from 9 May 1767, gives an indication of the showman behind it. The notice, in Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal, claims that it ‘is now, with great expense and labour, made the completest swimming bath in England, being constantly supplied with fresh water, and is so safe from the gradual depths in it, that young gentlemen may soon learn that pleasing, beneficial and useful exercise of swimming, without the least fear or dread of danger’.[2]

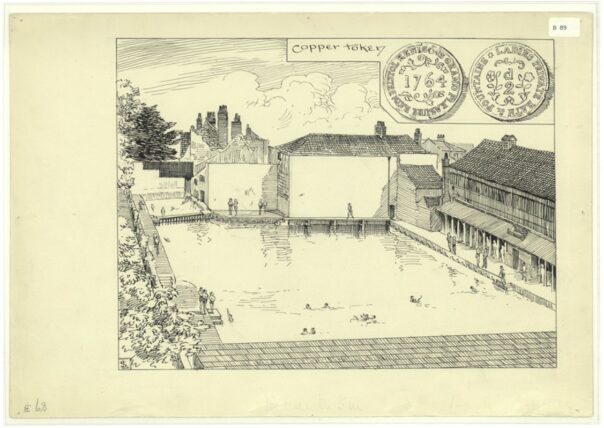

The main pool, for men, was roughly rectangular, 138 feet long and 84 feet wide. Around the perimeter were ‘neat apartments for gentlemen to undress in’. The newspaper goes on to describe an adjacent smaller pool reserved for women, the ‘ladies private bath’. Rennison boasts of the water having received so many plaudits ‘for its milky, mild and salubrious qualities that it would be ostentatious to speak any further of it’.

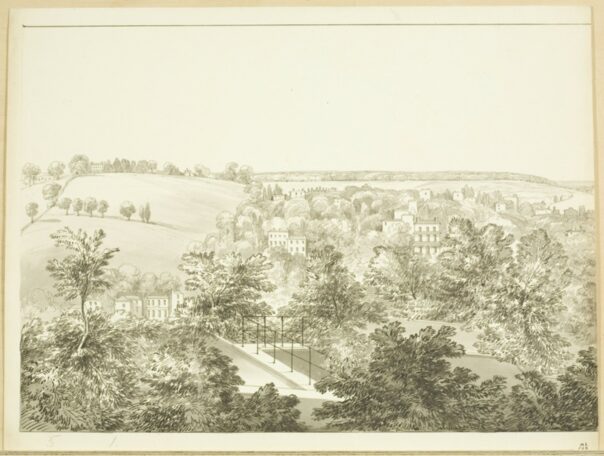

Montpelier was an attractive and prosperous suburb, still partly in the Gloucestershire countryside. In 1747 Rennison had acquired a snuff mill, paying an annual rent of £16 on a 17-year lease. It stood alongside Cutler’s Mill Brook, which flows into the River Frome. Bristolians today know the location as Bath Buildings.

The brook would supply water to the new baths. They were first advertised when Rennison bought the property at auction in September 1764. By then, his swimming pools were already established as a commercial enterprise. The entry charge was just two pennies (2d), or you could pay a cheap annual subscription, making it widely affordable. Advance publicity for the auction claimed the Baths were already ‘much frequented’, bringing in an annual income of between £30 and £40.[3]

The Bristol chronicler John Latimer estimated that Rennison’s pool was in use by paying customers from 1747, the year he first rented the mill.[4] Initially, Rennison also pursued his artisan trade of thread-making on the site. This was the traditional pre-industrial way to spin wool, cotton, flax or silk, for sewing or weaving. It involved cleaning, separating and straightening out the raw fibres, before twisting them to the desired thickness of your thread on a spinning wheel.[5] The site, known as Terrett’s Mill, was originally a corn mill. It had been adapted around 1727 for making and dyeing thread, then grinding snuff, which Rennison also continued.

Rennison struggled to earn a living from thread and snuff alone. He had noticed that a pond on the mill premises was a popular spot for boys to go for a summer dip. This instinctive businessman now had the bright idea of charging for admission. Rennison built an outdoor pool, backing onto the pond and supplied by it from the brook. He added dressing rooms and a coffee house, which he soon converted into the Old England tavern. A riverside ‘pleasure garden’ was also developed, with a small island in it. Rennison lived with his wife Mary and their three children in a house adjoining the pub.[6]

Thomas Rennison’s venture came 70 years before Britain’s oldest outdoor public swimming pool still in existence today. That distinction belongs to the magnificently restored Cleveland Pools in the city of Bath.[7] They first opened in 1817, and are now back in use by swimmers.. The original development, much grander than Rennison’s, was built on the River Avon near the village of Bathwick. It was separate from the famous Roman Baths, which had made Bath the height of Georgian fashion.

The Cleveland Pools were fully planned by the City Surveyor, together with the Mayor of Bath, landowners and other local grandees. Their team included a distinguished architect, John Pinch the Elder. He had designed some of the city’s iconic residential crescents, and would ensure the pools matched that elegant style. Funding was provided by 85 initial subscribers from among Bath’s prosperous business and medical community. Each agreed to contribute one or two guineas a year.

The outdoor Peerless Pool in central London pre-dated even Rennison’s. It was built in 1743 by William Kemp, a well connected jeweller. Like Rennison, he converted an ancient pond into a ‘pleasure bath’ for swimmers. His pool measured 170 feet long, over 100 feet wide and three to five deep. It had marble steps descending to a fine gravel bottom, through which springs bubbled up. Kemp surrounded his pool with an embankment and trees, and even provided a small library in the marble entrance lobby. The Peerless served a far more affluent clientele than its Bristol contemporary, charging up to two shillings per visit (12 times more than Rennison’s).[8]

Rennison’s Baths were certainly cheap, albeit rough and ready, to cater for the mass market. He reinvented swimming as a commercial business and popular recreation, affordable to ordinary working men and women. This was Thomas Rennison’s great lasting legacy.

However, he also targeted gentlemen and ladies from the fashionable Hot Wells mineral water spa across town. He offered evening musical concerts in the Old England and its ‘tea gardens’. A press notice in June 1782 gave more information. The concerts took place every Monday and Thursday from 6pm, throughout the summer season. The entrance fee was one shilling, to include tea or coffee. Alcohol was available in the tavern as usual.[9]

The swimming pool enterprise was a big gamble, especially for a businessman relying on borrowed money. Until the late 1700s, ‘cold baths’ in England had a mainly healing role, and very little actual swimming went on. The idea was to take a quick plunge and immerse your body in the water, without much movement. These baths were usually found on the estates of wealthy landed gentry, either in a separate bath house in the grounds or inside the main house, for use by themselves, family and friends.[10]

A good Bristol example is a cold water plunge pool, built in 1790, inside the home of a Caribbean plantation and slave owner, John Pinney, in Great George Street. Nowadays, it’s open to the public as the Georgian House, where you will find the pool in the basement. Pinney’s morning routine included jumping into the cold water to energise him for the day ahead.

River bathing appealed to a wider public in the 18th century, especially to young working men. In an era before domestic running water was common, the nearest river or brook could be the best place to wash, and to cool off in the summer.[11] Also, it was usually free. Men often bathed in rivers naked – a practice frowned on by the authorities and made illegal in Bath, for instance, from 1801. The city Corporation had already banned nudity in the Roman Baths spa from 1737, setting a pattern of decorum followed later by other spas. The clampdown in Bath applied to both men and women:

‘It is ordered…that no male person above the age of 10…shall go into any bath…without a pair of drawers and a waistcoat on their bodies…no female person shall go into a bath…without a decent shift on their bodies.’[12]

At Rennison’s, the rules about covering up were far more lax, right up to the late 19th century. A report to Bristol’s Baths and Wash Houses Committee in 1897 stated that a sudden drop in attendance there might be linked to the enforcement of wearing a bathing costume. A press article claimed the true reason was that swimmers at Rennison’s had to bathe in ‘putrid fluid’.[13]

One 18th century enthusiast for river bathing in Bristol was a professional accountant and amateur doctor named William Dyer (1730-1801). He treated local people’s ailments with his own herbal remedies. William kept a diary of his activities in note form, some of which has survived. In a brief entry for 7 June 1762, Dyer recorded bathing in the River Malago, a brook flowing through Bedminster:

‘Rose at 5 went to Mallow-go slum and plunged myself in the water.’[14]

In later years, the Malago would disappear under a culvert. In Dyer’s era, there must have been a bathing place. A diary entry in February 1756 noted that William had ‘long accustomed’ himself to cold bathing ‘even in frost and snow’. In May 1757, Dyer reported subscribing for a year for his wife to bathe at Rennison’s Baths. He paid 10s 6d, or half a guinea, for the subscription, which also entitled William himself to bathe there, if he brought his own towel.

A place for swimming in the River Frome was also available at Dyer’s time of writing. In July 1755, a notice in Felix Farley’s Journal informed readers that the Old Fox pub, at Baptist Mills, had ‘a bathing place in the River Froom, with commodious dressing houses’.[15] Both here and Rennison’s were recommended to visitors in the Matthews Complete Guide to Bristol of 1794.[16]

Thomas Rennison’s swimming pools and tavern lay just outside the city boundary in Gloucestershire, beyond the civic jurisdiction of Bristol. Rennison, with a crowd of his friends at the Old England, took full advantage to thumb their noses at the authorities. They held an annual Montpelier Bean Feast, at which a mock mayor, sheriffs and other dignitaries were elected, Rennison presided over the entertainment, styling himself jocularly as the so-called ‘Governor of the Colony of Newfoundland’.

It was a parody of Bristol’s civic ceremonies. According to Latimer, there were wild parties, with ‘various high jinks played by the not too abstemious revellers’.[17] Rennison’s antics created an image for Montpelier that still lingers. It’s often described as ‘bohemian’ in character – a bit unconventional and alternative.

Rennison’s thread

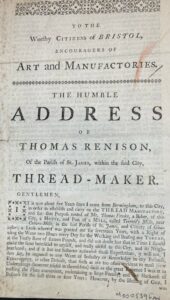

During his early struggles in Bristol as a thread maker, Rennison caused another stir with a dramatic public appeal for financial help. He wrote a pamphlet with the title: ‘The Humble Address of Thomas Rennison Thread-Maker’. A secondary heading follows: ‘To the Worthy Citizens of Bristol, Encouragers of Art and Manufactories’.[18]

Rennison makes a plea for sympathy, alleging undeserved cruel treatment by his landlord at Terrett’s Mill. His opening words state: ‘It is now about five years since I came from Birmingham to this city…’ There is no record of when that was. However, we know his mill tenure in Bristol started in 1747. The pamphlet tells us that Rennison was leasing the mill from its owner Thomas Vowles, a local baker. Vowles had adapted it for making snuff, which was fashionable just then.

The lease gave Rennison ‘a right of using the water two hours every day for the working and beating my thread’. After three or four years of slack business, while ‘maintaining a large family’, he admits falling into arrears on his £16 annual rent. Rennison claims his landlord’s response was to demand cancellation of the lease and to seize ‘a valuable parcel of thread’ from him.

‘The next day my landlord came to know my determination, and asked me whether it was peace or war?’ I must own the expression daunted me very much; but recovering my surprise, I replied: ‘Peace, I hope.’

Vowles gave him five days to pay up, after which all Rennison’s thread-making materials would be sold off. When still no money was forthcoming, ‘the goods were appraised and some part sold that very night’. Vowles then sent in some heavy-handed cronies:

‘As soon as opportunity would permit, my landlord came, and six or eight with him, with lighted candles, and beat down in a violent manner all before them; taking many things of value, which were not included in the Inventory. But his principal design was to distress my family and totally stop my trade.’

Rennison describes how they went about it: ‘…by pulling to pieces the twisting mills… throwing away the indigo fatt [sic] and all the liquors in the dye-house; also a black fatt, which requires months to prepare it for use, and diverse ingredients for dyeing entirely wasted, which was of great value.’

Indigo is an organic blue dye, extracted from the leaves of the indigo plant. It was traditionally used to dye textiles a rich, deep blue. Black was the favourite clothes colour, but hardest to achieve satisfactorily in Rennison’s time. The best ingredient for black dye was logwood, from a tree cultivated in Jamaica and imported through Bristol.[19]

In the ‘Humble Address’, Rennison does not specify what kind of thread he made. Wool was traditional for clothing, but that industry had gone into decline in Bristol. By the mid 18th century, it was being eclipsed by cotton. There is no record of industrial cotton manufacturing in Bristol until about 1790.[20] However, the port records show that bags of cotton from the Caribbean and America were being shipped to Bristol much earlier. For example, transatlantic voyages from Jamaica and New York, listed for the year 1723, include a ship with a cargo of 37 tons of logwood, 27 bags of cotton and 11 casks of indigo.[21]

The ‘liquor’ referred to by Rennison consisted of plant extract for the dye colour required, mixed with water, in which the fibres had to be soaked and agitated, or ‘beaten’. The mixture could then be reused several times.[22] Rennison stored it in containers for that purpose. No wonder he was so furious about the destruction of his expensive ingredients. The ‘Humble Address’ comments: ‘By these rash proceedings, I have been under the hard necessity to return several considerable orders from London and the country – to my great detriment.’

After this litany of moans, Rennison does express some hope of recovery – by raising £200 to £2,000 from investors in Bristol. The ‘Humble Address’ then moves into fake news territory, with a claim that ‘one thread maker in Birmingham employs more than a thousand poor people…I hope it is not impossible to draw some part of that branch into this part of the kingdom…’

In reality, no thread maker in Birmingham employed more than a few workers in those early days of the Industrial Revolution. Cotton spinning was still largely done by hand on a wheel in people’s homes. The first mechanised cotton mill had been set up in Birmingham during Rennison’s time there, but it proved a commercial flop.[23]

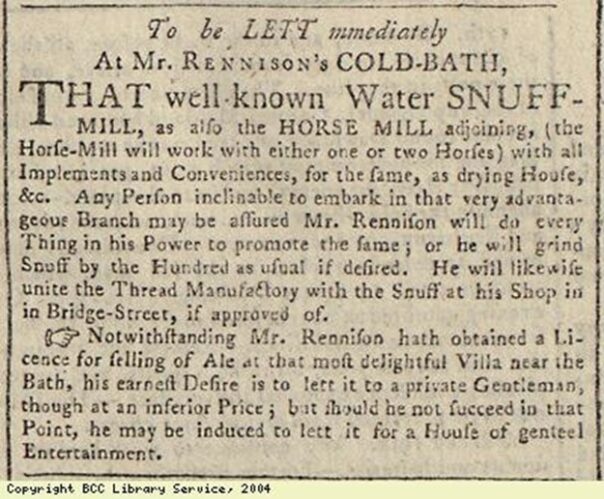

The ‘Humble Address’ is eloquently written – the work of an educated man. How much the appeal raised is unknown, but Rennison kept his thread and snuff mills in use. A 1775 directory listed ‘Thomas Rennison’ as a thread maker at 20 Bridge Street.[24] That same Old City address was a thread and snuff shop in 1780, when Rennison advertised for let his ‘water snuff mill’ and adjacent ‘horse [powered] mill’ in Montpelier.[25]

Rennison’s family

Rennison was born in 1707 in the Derbyshire village of Newton Solney, on the border with Staffordshire. Thomas’s father, John Rennison, was a yeoman farmer, with small estates in Newton Solney and two nearby villages. Thomas’s mother Sarah was also a local.[26]

The family’s ancestry as farmers there stretched back to the 16th century. Their original surname was Reynoldson, gradually morphing into Renison (with a single ‘n’), then finally Rennison. They owned the freehold to about 100 acres of land and a farmhouse, courtesy of their neighbouring gentry, the Every family.

Thomas Rennison had an older sister, Sarah (b.1697), and two older brothers – William (b.1699) and John (b.1701). All were baptised in Newton Solney Parish Church.[27] Their history reveals that family members over several generations lived way beyond their means, building up a massive spiral of debt.

John Rennison, the father, died in 1727, leaving unspecified debts. His will stipulated they must all be paid off from his estate. The eldest son, William, inherited the farm, on condition that he gave his brother John £100, and Thomas £200, within a strict time frame.[28]

Rennison in Birmingham

Thomas was due to receive his inheritance money on completion of a seven-year apprenticeship to a thread maker in Birmingham, Thomas Merrix. The boy’s father John had sent him there in 1723, as a 16-year-old, to learn a trade.[29] Rennison was given board and lodging with the Merrix family, in return for his labour at their small workshop in Moat Lane.[30] This ran alongside an ancient circular moat, surrounding land where a fortressed manor house had once stood.

It was now, at the very beginning of the Industrial Revolution, a thriving area packed with artisan craftsmen and traders, a stone’s throw from the Bull Ring market place.[31] In 1739, a decade after their father’s death, Thomas was still owed his inheritance. So much interest had accrued, plus legal penalties, that William Rennison’s £200 debt to Thomas had now grown to almost £2,000.[32]

In 1742, both brothers found themselves in court, facing separate actions for debt. William Rennison’s case involved almost £500, owed to three Derbyshire traders.[33] The Rennison family were subsequently obliged to sell their farmhouse and all their land to the Everys.[34]

Meanwhile, Thomas Rennison was declared bankrupt in Birmingham. He was listed as such in the Gentleman’s Magazine and Aris’s Birmingham Gazette.[35] However, neither report gave further details. There is no record of whether the bankruptcy resulted from Thomas’s family debts in Derbyshire, or his thread-making in Birmingham, or both.

Information is sparse on Thomas Rennison’s entire 20 years in Birmingham. We cannot even be certain he set up his own business. We have only his word for it, in the subsequent ‘Humble Address’, that his aim in Bristol was to ‘carry on the thread manufactory’ from Birmingham. However, parish records tell us that Thomas Rennison married Mary Shaw on 16 August 1732 at Aston St Peter and St Paul Church, Birmingham. Their daughter Sarah was baptised at St Martin’s, Birmingham, on 3 March 1735, and their son Thomas on 30 August 1738, in the same church.[36]

Lady Well

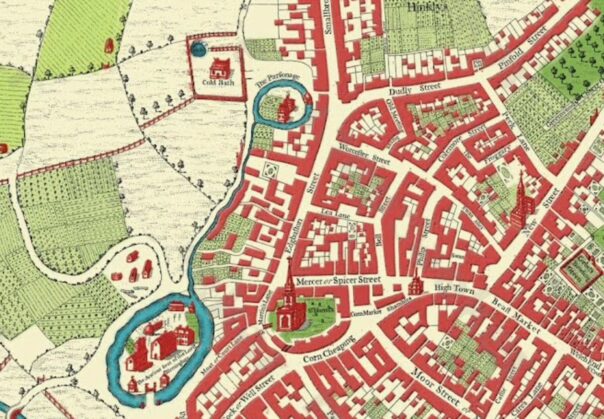

Before we return to Rennison’s Baths, it’s worth mentioning another lost public swimming pool – in Birmingham – which also pre-dates all the oldest ones still intact today. The Lady Well Pleasure Bath opened for swimming in about 1773, or earlier. A pool was in use long before that for the health benefits of its spring waters, and is even marked as ‘Cold Bath’ on the 1731 Westley map of Birmingham, which was available during Rennison’s period in the town. (You can see it at the top left of the map above).

The 18th century Birmingham chronicler William Hutton wrote about the baths in glowing terms in 1782:

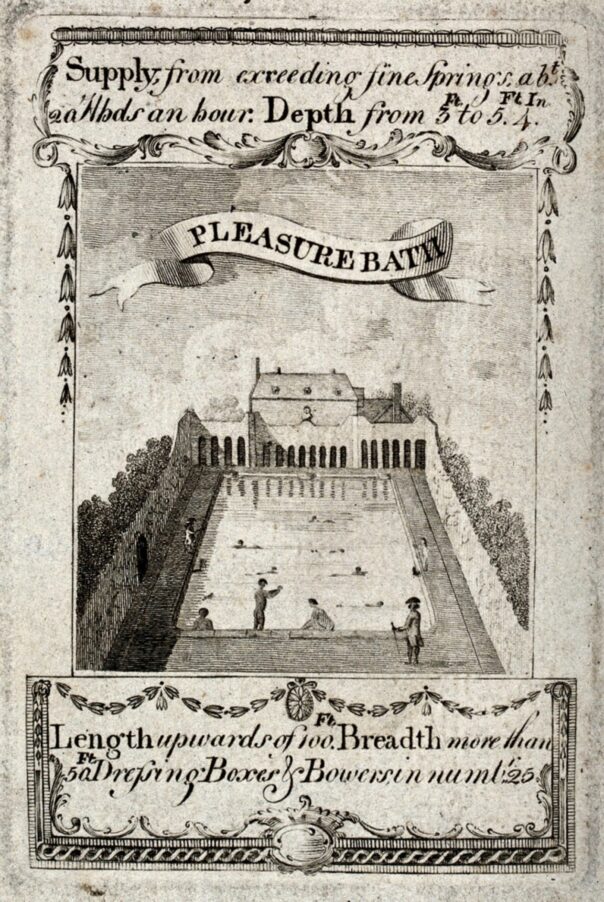

‘At Lady Well are the most complete baths in the whole island. There are seven in number; erected at the expense of £2,000. Accommodation is ever ready for Hot or Cold Bathing; for immersion or amusement; with conveniency for sweating; that appropriated for swimming is 18 yards by 36, situated in the centre of a garden, in which are 24 private undressing houses… Pleasure and health are the guardians of the place.’[37]

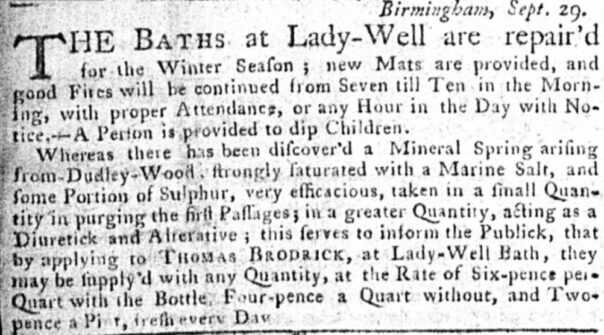

Hutton is vague about how long Lady Well had catered for swimming, in addition to therapeutic bathing. One of the earliest press advertisements for it, in Aris’s Birmingham Gazette, is dated 29 September 1756: ‘The baths at Lady Well are repaired for the winter season; new mats are provided…A person is provided to dip children.’[38]

The proprietor’s name is given as Thomas Brodrick. In this advertisement, he puts most emphasis on the health benefits of drinking his bottled mineral water, supplied by a powerful spring. It’s an indication that in 1756, swimming had not yet become part of the service at Lady Well.

The notice was published a decade after Thomas Rennison left Birmingham. However, Lady Well was already a landmark when Rennison lived and worked just a short stroll away in Moat Lane. It may even have inspired his swimming baths idea in Bristol.

Rennison’s Baths

There was clearly a significant difference between Rennison’s Baths and other early public swimming pools. The ones in London, Bath and Birmingham were all funded by prosperous local businessmen, carefully planned and for middle or upper class customers. However, in Bristol Thomas Rennison deliberately made his baths cheap and cheerful to bring in the crowds. Unfortunately, Rennison purchased and redeveloped the mill site with money he did not have.

A local history writer, Mary Wright, pored over the title deeds of Terrett’s Mill for her book ‘Montpelier – a Bristol Suburb’ (2004). She discovered that soon after purchasing the mill site in 1764, Rennison mortgaged it for £400. He then borrowed a further £200 to finance construction of the Ladies’ Pool and the Old England tavern. Rennison later remortgaged the premises, this time for £1,000.[39] Why lenders continued to fund him is a mystery.

Near the end of Thomas senior’s long life, his creditors may finally have caught up with him again. There’s evidence that Rennison wass jailed for debt – in his eighties. Historical records list all debtors imprisoned in London’s Newgate Gaol from the late 18th century onwards. Over a six-month period, from December 1791 to June 1792, ‘Thomas Rennison’ was named as a debtor in 10 successive calendar lists of prisoners held in Newgate.[40] This man could have been a different Thomas Rennison who, by coincidence, had also fallen into debt. But there seems no other plausible candidate, so maybe it was indeed our Rennison.

On the old rogue’s death that same year, 1792, his son Thomas Rennison junior (1738-1802) inherited the mill, baths and tavern. He proved no better at finance, as the business staggered into the next century. After Rennison junior’s death in 1802, his own eldest son – also called Thomas (b.1760) – took ownership, while the debts still mounted.[41] Rennison’s Baths kept going during the Napoleonic Wars thanks to the new owner’s sister-in-law.

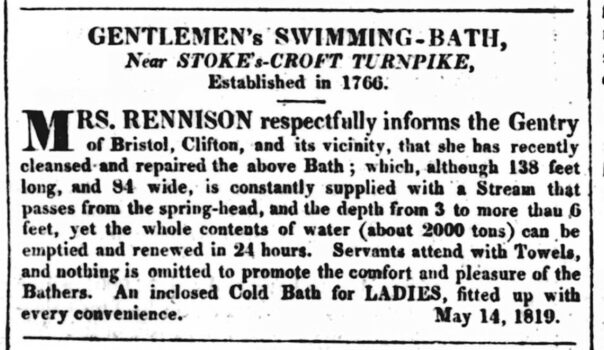

Sarah Burcher (c 1770-1851) had married John Rennison (1781-1848), the youngest of Thomas senior’s grandsons, in 1801.[42] While the men struggled with cash flow, she took charge of the Baths management herself. Sarah placed her own advertisement in the Bristol Times & Mirror in July 1813, and again in April 1819, telling told the public about her renovation of both the men’s and women’s pools:

‘Mrs Rennison respectfully informs the Gentlemen of Bristol, Clifton and the Hotwells that she has recently cleansed and repaired the above Baths, which, although 138 feet long and 84 wide, are constantly supplied with a stream that passes from a spring-head; and the depth being from three to more than six feet, yet the whole contents of water (2,000 tons) can be emptied and renewed in 24 hours.’[43]

Sarah’s re-launch of the baths could not prevent their owner Thomas Rennison, grandson of the founder, being declared bankrupt in 1818. The following year, legal administrators of his estate put the whole mill site up for sale, including the baths and tavern, to clear the most pressing debts. They held at least two auctions, but little appears to have been sold.[44]

The property passed to bankrupt Thomas’s next-in-line brother, William Cox Rennison (1779-1848). He decided to settle, finally, all the family debts. In a series of auctions from 1822, William sold off everything on the premises, except for the baths, but including the Old England.[45] William made enough profit to become, in the 1830s, a gentleman of independent means.

John and wife Sarah stayed in charge of the baths until 1849. Ownership in this period is unclear, but it appears to have fallen to John Rennison, certainly after his older brother William died in 1848. Sarah and both brothers had become part of a whole community living in cottages for rent, which had recently[46] sprung up on land behind the Baths and in fields up the hill, nowadays called St Andrews Road.

The 1841 Census listed an astonishing total of 100 people all at an address given as Rennison’s Baths, half of them children. They were in at least 20 separate households, of working men and women from many different professions. They included an ironmonger, tailor, laundress, coachman, carpenter, coach painter, gardener, labourer, accountant, shoemaker, hat manufacturer – and a publican, George Stokes of the Old England. The latter was living in the tavern with his wife Mary and their six young children.

John and Sarah Rennison, likewise William, were Unitarians, and therefore religious Nonconformists. By 1851, each had been laid to rest at the Unitarian burial ground in Brunswick Square, St Pauls.[47]

From 1849, Rennison’s Baths simply carried on – under new ownership but keeping the old name. Bristol Corporation now opened the city’s first municipal baths, at Broad Weir. At first, they were intended not for swimming, but as somewhere for people to wash themselves and their clothes. The Corporation had responded to new legislation, the 1846 Baths and Wash-houses Act, obliging councils to provide such facilities.[48]

In 1850, Bristol’s second public swimming pool opened – a whole century after the first. The Victoria Baths in Clifton were designed by an architect, R.S. Pope, and constructed by a local builder, William Hamley. The Bristol Mercury gave a description:

‘The dimensions of this noble swimming bath are 132 feet by 54 foot; the depth gradually sloping down from 3 feet to 7 foot. In the centre is an ornamental vase, and at the end are the apartments afforded to the bather. These are entered from behind, and open immediately upon the water.’[49] The price of a single admission to this pool was one shilling – yet again, more expensive than Rennison’s. The Victoria Baths have survived into modern times. After a period of closure, the main pool was restored to its former glory, and is now the Clifton Lido.

Rennison’s water

Complaints about swimming through slime at Rennison’s Baths increased during the mid 19th century. Dirty polluted water had long been a problem for the whole city, but it worsened in the 1840s, as the population of Bristol rapidly expanded. On the supply side, Bristol progressed from being ‘worse supplied with water than any great city in England’ to being top-rated, in just two years. This was according to a government inspector’s report in 1850.[50] George Clark had been commissioned to investigate the state of water supply, drainage, sanitation and sewers across Bristol. He found that most people still had to collect water in buckets from wells and standpipes.

Supply was transformed from 1846, when a team of engineers and public health experts set up their own water company, Bristol Water Works. They laid big solid pipes to carry water from springs in the Mendips to new store reservoirs at Barrow Gurney, just south of the city. From there, up to 600 thousand gallons a day could be piped to all parts of Bristol and its suburbs.

It was the opposite with domestic sanitation and disposal of sewage, for which responsibility lay with the Corporation. There was great concern about a higher mortality rate in Bristol than most other big cities, following increasingly severe cholera outbreaks in 1832 and the 1840s. Only Manchester and Liverpool fared worse in terms of bad health.

Even a prosperous suburb like Montpelier had no drainage. Human excrement, horse manure and other waste collected in cess pools in upper Montpelier, or seeped directly into Cutler’s Mill Brook from the privies of homes lower down.

Clark’s report found the pollution was increased further by effluent from new housing in Redland, Cotham and Horfield. It was carried by two streams, forming ‘filthy open ditches’ that merged with Cutler’s Mill Brook. The brook then flowed on past the Baths and into the River Frome at Baptist Mills, to join even fouler and smellier sludge in the Old City. At Rennison’s, Clark observed, ‘the channel is peculiarly filthy and irregular. Upon it is a large dirty pool, at the back of Rennison’s Bath, which it, until recently, supplied with water.’[51]

The clean water supplied to Rennison’s by Bristol Water Works obviously made some difference. However, a letter to the government inspector from 25 signatories, complaining about the filthy brook crossing Montpelier, typified local anger.

‘This open ditch….smells dreadfully the whole year, and in hot dry weather the nauseous stench is unsupportable, producing sickness, weakness, languor and fever, so that many have been ordered by their medical men to quit the neighbourhood in consequence, and some have died of fevers from this ditch.’[52]

Among many complaints about the water quality at Rennison’s, this very graphic one filtered into the press, soon after the baths were purchased by the Corporation in 1892. Its author summarised the main pool as ‘green, offensive and stagnant’, and explained why:

‘The bath, being an open-air one, collects all the dirt and grime from the atmosphere, and added to this is the fact that the bath is patronised by more bathers during the season than any other of the Corporation baths; yet the water is allowed to remain unchanged week after week, until it becomes… a slimy, dirty, soup-like fluid…Imagine the horror and repugnance which fills the breast of the hapless bather who has unwittingly swallowed a mouthful of this horrible aqua impura!’[53]

Yet still the crowds flocked in. Rennison’s total attendance for the summer of 1896 was 33,000 – despite Bristol having six public pools by then.[54] Post-Rennison owners organised swimming lessons for schoolchildren and competitive races for all ages. A gala at Rennison’s in September 1865 took place in front of many spectators, with a brass band and prizes. The Western Daily Press gave details:

‘One race was a juvenile race, between Master J.W Searle, 8 years of age, who has only been under tuition for a month, and a little girl named Alice Maude Brentnell, said to be the youngest female swimmer in Bristol. The race was well contested, and was ultimately won by the little girl, who distanced her opponent by one foot only.’[55]

This and other galas at Rennison’s also featured a local high-board diver, Robert Backwell, who owned the Baths for 13 years. A day of competition in August 1849 received a press build-up in advance:

‘M.R.B., the celebrated diver, will be in attendance, and dive from an eminence of more than fifty feet with his boots in his hands, and will put them on before rising to the surface.’[56]

Conclusion

Rennison’s Baths had survived many adversities, but the First World War proved fatal. Bristol Corporation neglected repairs and customer numbers dwindled. The Ladies’ Pool dried up, becoming full of weeds and unusable. A report to the city’s Health Committee in June 1914 expressed serious concern about ‘half an inch of slime’ in the bigger pool. Permanent closure followed in 1916. The baths were soon filled in – and a new era began.

Thomas Rennison senior, the founder, would have been amazed that his creation lasted so long. He was a profligate opportunist, but with the Georgian spirit of enterprise. After bankruptcy in Birmingham, he launched Rennison’s Baths just to keep his head above water. He ended up making public swimming pools a big commercial leisure attraction, for anyone with a couple of pennies to spare. Thomas Rennison and his baths deserve proper recognition for giving many generations immense pleasure – and a brief escape from their arduous working lives.

A pdf version of this article with the original formatting is downloadable: Thomas Rennison and his Grand Pleasure Bath.

This article was researched and written by Peter Cullimore, author of two non-profit books on Georgian Bristol. The first, ‘Saints, Crooks & Slavers’, tells the story of his house in Montpelier and its past residents. The second, ‘Pills, Shocks & Jabs’, is about the influence of Quaker doctors on the city’s 18th century healthcare. Both are published by Bristol Books: www.bristolbooks.org

Feedback welcome: email cullimorepeter@gmail.com

References

[1] Aris’s Birmingham Gazette, February 1742

[2] Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal, 9 May 1767

[3] Ditto, 22 September 1764

[4] John Latimer, ‘Annals of Bristol: 18th Century’, 1893, p. 269

[5] ‘Textile Manufacture during the British Industrial Revolution’, Wikipedia

[6] Mary Wright, ‘Montpelier : a Bristol Suburb’, Phillimore, 2004, p. 39

[7] Linda Watts & the Cleveland Pools Trust, ‘Swimming Through History: the Cleveland Pools, Bath’, 2022, p5, pp. 14-31

[8] Warwick Wroth, ‘The London Pleasure Gardens of the 18th Century’, Macmillan, 1896, pp.81-85

[9] Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal, 22 June 1782

[10] Clare Hickman, ‘Taking the Plunge: 18th century bath houses & plunge pools’, article for Buildings Conservation Directory, 2019

[11] Louise Falcini, ‘Cleanliness and the Poor in 18th century London’, PhD thesis, University of Reading, 2018, pp. 22-23

[12] Penelope Byrde, ‘That Frightful and Unbecoming Dress: Clothes for Spa Bathing at Bath’, article for Costume journal, vol 21, issue 1, 1987

[13] Bristol Magpie, 5 August 1897

[14] Jonathan Barry (editor), ‘The Diary of William Dyer’, Bristol Record Society, 2012, Notes p. 110

[15] Latimer, p. 315

Bristol Journal, 19 July 1755

[16] William Matthews, the Complete Bristol Guide, 1794, p. 91

[17] Latimer, p. 269

[18] ‘The Humble Address of Thomas Renison Thread Maker’, Bristol Reference Library, B21795

[19] David and Sue Richardson, Asian Textile Studies website

[20] S.J. Jones, ‘The Cotton Industry in Bristol’, Institute of British Geographers papers no.13, 1947, pp. 62-67

[21] W.E Minchinton (editor), ‘The Trade of Bristol in the 18th Century’, Bristol Record Society, 1957, pp. 5-6

[22] Water in Textiles and Fashion’, Woodhead Publishing, 2019, pp. 175-194

[23] Joseph Hill and Robert Dent, ‘Memorials of the Old Square’, 1903, Wellcome Collection, pp. 76-7;

Industry and Trade 1500-1800, British History Online, 2019

The first mechanised cotton mill, with a system of rollers powered by two donkeys rotating a wheel, was patented by Birmingham inventor Lewis Paul in 1738. But he and partner John Wyatt ran out of money and their Upper Priory Mill soon closed. The first Birmingham works to employ 1,000 was Matthew Boulton’s Soho Manufactory, for metal products, in about 1770.

[24] Sketchley’s Bristol Directory of 1775

[25] Bonner & Middleton’s Bristol Journal, 1 January 1780

[26] Michael Day and Maxwell Craven, ‘Newton Solney’, 2010, p. 55

[27] Derbyshire Church of England Baptisms, Marriages & Burials, Ancestry

[28] Probate copy of will of John Rennison, of Newton Solney, yeoman, proved at Lichfield 20 April 1728, Derbyshire Record Office, ref D5236/29/2/07

[29] UK Register of Duties for Apprentices’ Indentures, Ancestry

[30] Birmingham Archives and Collections (BA&C), catalogue description: ‘Articles of agreement between James Baker of Birmingham, chandler, and Thomas Merrix of Birmingham, threadmaker, concerning a party wall between premises in Moat Lane, 1 September 1724’, MS 3375/428893

[31] Simon Buteux, ‘Beneath the Bull Ring’, Brewin Books, 2003, p. 67

[32] Derbyshire Record Office, extract from articles of agreement between William and Thomas Rennison, 1739, ref. D5236/29/17/08

[33] Warrants from the Court of Common Bench at Westminster, for lawyers to appear on behalf of William Rennison , in an action for debt, March 1742. Derbyshire Record Office, D5236/29/29-31/13

[34] Derbyshire Record Office, catalogue description of documents relating to Every family, D5236

[35] The Gentlemen’s Magazine (publisher Edward Cave), Vol 12, February 1742, Harvard University Collection digitised by Google, p. 108

Aris’s Birmingham Gazette, February 1742

[36] Birmingham Church of England Baptisms, Marriages & Burials, Ancestry

[37] William Hutton, ‘An History of Birmingham’, 1783, Project Gutenberg e-book, p. 7

[38] Aris’s Birmingham Gazette, 4 October 1756

[39] Mary Wright, ‘Montpelier: A Bristol Suburb’, Phillimore, 2004, p. 40

[40] UK Prison Commission Records, ‘List of Prisoners on the Common Side’ [unable to pay for their accommodation], Newgate Prison London, Ancestry

[41] Wright, p.40

[42] Bristol Nonconformist Baptism, Marriage & Burial Registers, Ancestry

[43] Bristol Times & Mirror, 9 July 1814

[44] Bath Chronicle & Weekly Gazette, 22 April 1819

Bristol Mirror, 20 May 1820

[45] Bristol Mirror, 10 August 1822

[46] 1841 Census, Ancestry

[47] Bristol Nonconformist Baptism, Marriage & Burial Registers, Ancestry

[48] Agnes Campbell, ‘Report on Public Baths and Wash-houses in the United Kingdom’, Edinburgh University Press, 1918, p.4

George T. Clark, Report to the General Board of Health, 1850, p. 188

[49] Bristol Mercury, 3 August 1850

[50] George T. Clark, Report to the General Board of Health, 1850, pp. 110-123

[51] Ditto, p. 121

[52] Ditto, p. 122

[53] Clifton & Redland Free Press, 9 July 1897

[54] Kelly’s 1897 Directory for Gloucestershire and historical guide to Bristol, p. 13

[55] Western Daily Press, 12 September 1865

[56] Bristol Times & Mirror, 11 August 1849

John Newman

Dear Sir,

I enjoyed your article on Rennisons Baths and the Old England Tavern.

I have an interest in Past Real Tennis Courts in Bristol, and recently came across a letter from William George written 20.5.1890 in which he quotes from the Bristol Guide of 1794 saying The Old England Coffee House and tea garden near Stoke Crofts turnpike ‘arenow open Amusements @for the athlete there are tennis-courts; and for those who are fond of bathing and swimming the spacious bath and dressing houses….’

Since Lawn tennis only started about 1870 and there are no known Royal Tennis courts in that region it is extremely interesting though I suspect a red herring or at most referring to some informal arrangement for a racket game.

Do you have any thoughts or comments?

Best wishes,

John Newman