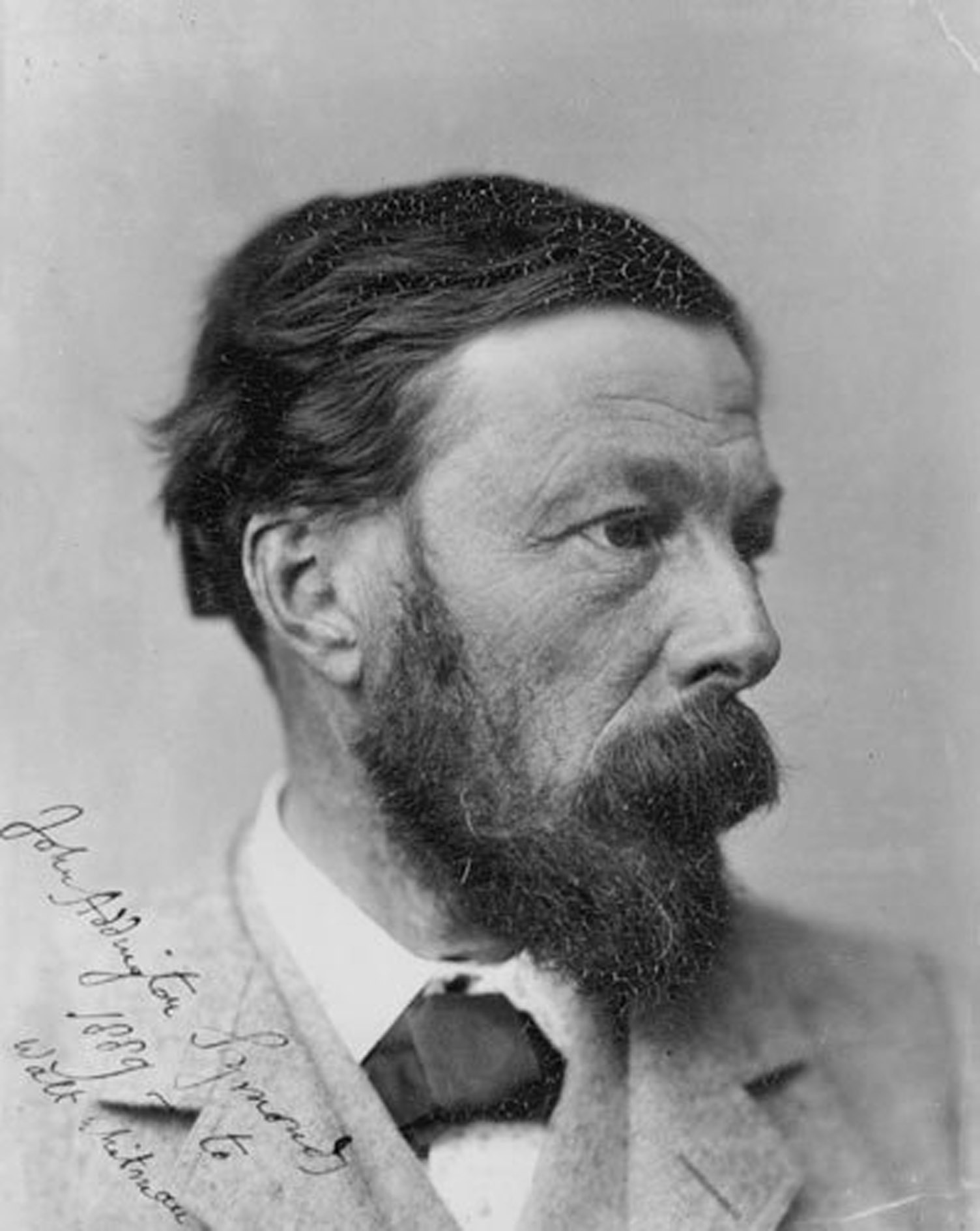

I have been interested, for some time now, in the writings of John Addington Symonds (1840-1893) mainly because of my researches into the legal censoring and subsequent bibliographical history of Volumes 1 and 2 of Havelock Ellis’s six volume Studies in the Psychology of Sex [Studies]. Symonds collaborated with Ellis on Sexual Inversion (homosexuality), which was originally Volume 1 of Studies and that volume is now considered an important if not foundational text in the early history of sexology. Although Symonds died in 1893, several years before the publication of Sexual Inversion, Ellis honoured Symonds’s contributions by making sure that Ellis and Symonds were noted as joint authors when the book was eventually published in 1897. No sooner had Sexual Inversion appeared in print than Symonds’s two literary executors, his wife Jane and his close friend Horatio Brown, took fright because they feared that the circulation of such a book would sully Symonds’s reputation. They made an agreement with the publisher, Dr. de Villiers, that they could purchase the remaining stock in order to pulp the entire edition. Undeterred Ellis made the necessary alterations to that almost vanished first edition and, a few months later, Dr. de Villiers republished what was in effect the second edition of Sexual Inversion only this time without any ‘incriminating’ evidence which might have pointed to Symonds’s original involvement in a book whose subject matter was still widely considered an abominable practice.

When I first came to live in Bristol, some three and a half years ago, I discovered, to my surprise, that Symonds was born in Clifton where he passed his childhood and part of his adolescence before being sent away to board at Harrow. After Symonds graduated from Oxford, he returned to live in Bristol and after he married Janet, the daughter of Frederick North the MP for Hastings, the two of them settled in Clifton where their four daughters were born. Eventually Symonds resolved to exile himself to Davos (Switzerland) mainly or perhaps only partly for reasons of health. Once settled in Davos Symonds became part of its small but significant homosexual community and, at the same time, forged close links with other communities of exiled homosexuals living even more openly in northern Italy. On the face of it Symonds’s self-imposed exile appears to have offered him the space to breath, to live and to write his life as a homosexual man.

When I first started researching Symonds’s Bristol connections I discovered that in 1999 the Clifton and Hotwells Improvement Society [CHIS] had erected a green plaque outside Symonds’s house, at 7 Victoria Square (Clifton), which is where he lived for a time with his wife and their daughters. Although that plaque reads: “John Addington Symonds (1840-1893) Poet, Critic, Historian, Lived Here 1868-71” it makes no mention, or reference, to Symonds’s homosexuality. If anybody suggests that this kind of plaque is too small to encompass that sort of ‘snippet’ of information then I would invite them to turn to the archive page of the CHIS website. Although the expanded entry lists Symonds’s various contributions to British cultural history, including his “biographies of Shelley (1878), Sir Philip Sidney (1886), Ben Jonson (1886), and Michelangelo (1893),” it still makes no mention, whatsoever, of his homosexuality. Nor does it mention A Problem in Modern Ethics; An Inquiry into the Phenomenon of Sexual Inversion, Symonds’s significant contribution to what used to be known as gay studies but which is now more generally known as LBGQT Rights. There is little excuse for these omissions because in 1964, some 35 years before the Symonds Plaque was erected, Phyllis Grosskurth discussed his homosexuality in The Woeful Victorian, her biography of Symonds. Grosskurth also edited Symonds’s Memoirs, albeit in a somewhat expurgated form, and these were published in 1984 under the subtitle “The Secret Homosexual Life of a Leading Nineteenth-Century Man of Letters”. To put it bluntly if anybody had cared to look more closely into Symonds’ biography in 1999 they should have known that Homosexuality was the moving force of Symonds’s life and that it coloured everything he did and thought.

It might also be of interest to readers if I added a short addendum to these comments with a few words about Symonds’s connections with Bristol gleaned from Grosskurth’s books and also from Amber Regis’s fine scholarly Critical Edition of Symonds’s full and unexpurgated Memoirs, published in paperback in 2017. There, is for example, Symonds’s touching account of his romantic adolescent friendship with the chorister Willy Dyer and a description of how the two of them “lay side by side in Leigh Woods and kissed.” This was, of course, before the opening of the suspension bridge, when Leigh Woods could only be reached from Clifton via the ferry. Another aspect of Symonds’s life, which might also interest Bristolians, concerns Symonds’s father, also called John Addington Symonds [Dr Symonds] who was a member of the Plymouth Brethren and an important Bristol physician. Dr Symonds had strong connections to the Blind Asylum, subsequently known as the Bristol Royal School and Workshops for the Blind, which used to be situated more or less on the site now occupied by the Wills Building at the top of Park Street. The Asylum was also almost opposite Berkeley Square where Dr Symonds and his family lived before they moved to Clifton Hill House which, on Dr Symonds’s death in 1871, passed to his son. In 1909 Clifton Hill House became the first hall of residence for women in south-west England and is now in the ownership of Bristol University.

Dr Symonds also merits research in his own right not just because he was Symonds’ father. In 2010 Sue Young added an entry on Dr John Addington Symonds (1807 – 1871) in her Sue Young Histories blog which is worth noting. Employing her usual dogged research Young has discovered that Dr Symonds was a ’secret’ patient of the homeopath James Manby Gully (1808-1883) “at a time when orthodox physicians were proclaiming they would not be seen even talking to a homeopath.” Tugging at this thread Young has discovered that Dr Symonds counted amongst his extensive circle many friends and staunch supporters of homeopathy. Whether or not Symonds knew about his father’s secret adherence to homeopathy he was clearly fond of his father and said of him: “‘He was open at all pores to culture, to art, to archaeology, to science, to literature.’” Having already traced something of the complex relationship between father and son, through my readings of Symonds’s Memoirs and having now discovered Sue Young’s fascinating research, I am left wondering if Dr Symonds’s secret homeopathic life might, in a small way, help to illuminate something of those psychological impulses which might have informed the secret homosexual life of his son.