Struggle or Starve is a compelling account of the 1932 Outdoor Relief riots in Belfast, an episode of widespread working-class unity while engaged in militant struggle that is often airbrushed over in favour of the more typical focus on Northern Ireland’s sectarian politics. Seán Mitchell is however a socialist from West Belfast who has finally given this unique event the historical study it has long deserved but not received.

The period under study in fact extends from the working-class of Northern Ireland’s harsh experience of the Great Depression that followed the 1929 Crash, when former bastions of Protestant ‘privilege’/full employment such as the Harland & Wolff shipyard imposed mass redundancies, up to the failure of Republican Congress in 1935.

The first chapter reviews the gradual formation of Northern Ireland from 1912-22, and the establishment of sectarianism as its key, if not sole, unifying principle. Political control was achieved through a one party state run by a Unionist Party of landowners and manufacturers that relied on the maintenance of Protestant privilege in jobs, houses, and in fact all areas of social function and existence. A repressive state apparatus with sectarian paramilitary police and the infamous Special Powers Act was all that was needed in 1922 to crush what was left of an exhausted Irish Republican movement, by then in the midst of its own civil war.

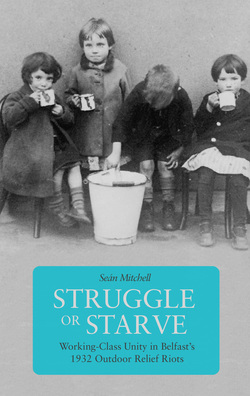

However, the chief resentment from the point of view of the combined Catholic/Protestant working class centred around the retention of the 19th Century workhouse system by the Unionist Party government, especially since in ‘mainland’ Britain it had been abolished in 1919. The workhouse was so hated that even in the conditions of direst poverty, workers would rather starve than enter it. So the Unionist government began to place emphasis on the system of ‘Outdoor Relief’, another hangover from the workhouse system whereby the unemployed worker remained at home but, in exchange for a pittance and a commitment to work on exhausting, pointless labour schemes, had to first undergo humiliating means and ‘willingness to work’ tests in front of a board of middle class puritans and ideologues.

From 1929-30 with the Great Depression and its severe impact on Northern Ireland’s already fragile economy, these resentments reached a boiling point that incidentally coincided with the formation of clandestine communist Revolutionary Workers’ Groups (RWGs) in an Irish context, set up as a vehicle by the Comintern to nurture the cadres with which it hoped to establish a future all-Ireland Communist Party.

In fact these cadres, although they received some help and training from Moscow were to a large extent independent operators, and ‘party discipline’ was often exceedingly difficult to establish over them. The lead Northern/Belfast operator was a man called Tommy Geehan, a former IRA operative who was also known as an excellent public speaker. He, alongside other working class communists from both sides of the sectarian divide began to set up an Outdoor Relief strike in the summer of 1932 that mobilised a mass social movement centred around key demands that for a period thwarted the best attempts of the Unionist establishment to divide it by playing the old tried and tested ‘Orange Card’.

Then, when the Unionist establishment decided to break the strikers by launching a violent guns-blazing attack by the police and ‘special constabulary’ on the predominantly Catholic Falls Road area alone, within minutes it had backfired spectacularly and ignited a full scale riot not only on the Falls – but also on the predominantly Protestant Shankill Road next door – which in turn quickly spread to all working class districts of Central, West and North Belfast alike and continued for several days without abating.

The result was that the Unionist establishment rapidly retreated in fear and key concessions were won, at least initially, and for the period of about a year or more afterwards the anti-sectarian unity that had been achieved in struggle remained solid and the RWGs continued to mobilise subsequent actions both north and south of the border, ending in a bitter railway strike of 1933-34 that even involved ‘solidarity actions’ by left-leaning elements of the IRA.

Seán Mitchell has done a commendable job in raising this event to the profile it deserves, using previously ignored primary sources and the tenets of ‘history from below’ to confound the dominant narratives that try to reduce everything in Northern Ireland down to a sectarian zero-sum game, whether these are Loyalist, Nationalist, or bourgeois establishment. Most compelling of all are the opportunities and possibilities it raises of achieving working class unity in Ireland – so long as no compromises are made with sectarianism or imperialism in the process – a vision that for a brief period, and had historical forces played out differently than they actually did, looked as if it might have come to fruition in the years 1932-35.

Kevin Boylan (April 2020)

You can purchase the book here.