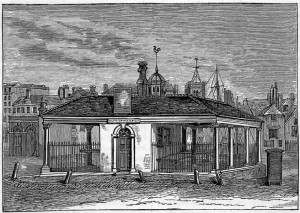

Taken from Bristol Past and Present by J. F. Nicholls and John Taylor, published in 1882

We now enter upon one of the most important eras in the modern history of our city. In 1831 the Bristol riots occurred in connection with the agitation for reform; Sir Charles Wetherell, the attorney-general under the Duke of Wellington’s administration, was a vigorous opponent of the emancipation of the Roman Catholics; on the second reading of the Relief Bill he opposed it in a trenchant, vigorous speech, notwithstanding the fact that the Government, of which he was a member, had introduced the measure. Greville says, “The Speaker said the only lucid interval Sir Charles had was that between his waistcoat and his breeches. When he speaks he unbuttons his braces, and in his vehement action his breeches fall down and his waistcoat runs up, so that there is a great interregnum. He is half mad, eccentric, ingenious, with great and varied information, and a coarse, vulgar mind, delighting in ribaldry and abuse, besides being an enthusiast; he is inflexibly honest, and with all his eccentricities highly honourable.” On 22nd March, 1830, the Duke dismissed him, and Sir Charles won high renown amongst the anti-Catholic party for the sacrifice he had made on principle. He was at this time the Recorder of Bristol, a position equivalent or nearly so to that of judge of the King’s bench, and on his entrance into Bristol in April to hold the Assize he was welcomed by an immense multitude with shouts of “No Popery! Wetherell for ever!” The mob attempted to take his horses from the carriage in order to draw him in triumph, and they spent their surplus energy in smashing the windows in the houses of the Catholics and of their chapel in Trenchard street. Sir Charles was only another instance of the instability of popular favour, for the Hosannahs of the day speedily gave place to malediction and outrage. His opposition to a reform of the Constitution was equally conscientious and even more obstinate. On July 8th, 1831, the second reading of the Reform Bill was carried by 367 to 231, and on the 12th the House attempted to go into committee; when a few of the Tories, deserted by their leaders, were headed by the ex-attorney-general, and for eight hours the small and dwindling body, by repeated divisions, obstructed the progress of the measure, until at half-past seven in the morning, with numbers diminished to twenty-four, they relinquished the struggle, just as the Liberal whips had sent out for a fresh relay of members from those who had taken a night’s rest. This extreme partisan spirit on the part of the chief criminal judge of the city greatly irritated the minds of the Bristol reformers, and when in his place in the House of Commons he spoke with contempt of a petition to the Lords which had, it was said, 20,000 Bristol signatures, and declared that there was a reaction against the bill, the indignation against him in the city was extreme. Cunning demagogues and unwise orators fostered the feeling and magnified the offence. Equally unwise antagonists of reform made defiant orations and added fuel to the angry passions of the multitude. There is no doubt but that Sir Charles was in some degree misled by the speeches and resolutions passed by those who had not sufficient perspicacity to gauge the feeling of the country, and was encouraged to fight by such meetings as the following:- On Friday, January 28th, a “loyal and constitutional meeting” in opposition to reform had been held at the “White Lion” tavern, Bristol, Mr. Alderman Daniel in the chair, when an address to his majesty and a petition to Parliament were unanimously adopted. The petition, after alluding to the disturbed state of the country where every artifice is practiced to inflame the passions of the people, and to diffuse discontent and dissatisfaction by a licentious press, states that it would be a fatal error if Parliament believed that a popular clamour for revolutionary innovations under the pretext of reform expresses the sense of the nation; that the respectable portion of the people have abstained from attending meetings called in advocacy of discontent and the disturbance of the public peace; that our admirable form of government, King, Lords and Commons is, of all political systems planned by human wisdom, the most perfect and complete; that any changes necessary must be corrected with caution, new elements introduced would destroy its very form and character; that the Protestant religion must be supported; vote by ballot denounced as a degrading theory; that rank and property naturally give an influence over those to whom they give support and the means of existence; that the kindly affection subsisting between these two classes, the employer and the employed, forms the best safeguard of social order which would be destroyed by giving the ballot; that the ballot would lead to universal suffrage, that such changes would be of fatal consequence to the state, and they pray that all attempts to introduce such measures may be met by a firm and decisive rejection.

*The Age we live in, 356.

This petition of the loyal and constitutional meeting called forth great exertions on the part of the reformers who got up counter-petitions, with 12,000 signatures which were presented to Parliament on the same night as that of the Tories. Mr. Hunt objected to the reception of the latter, on the ground of its being a printed paper and so contrary to rule.

At the dissolution of Parliament in April, at an immense mass meeting held in Queen square on the 26th it was determined to contest the election, and Edward Protheroe, jun., and James Evan Baillie were selected by the Whigs as the reform candidates. At a meeting of the Tories held at the ”White Lion” tavern their old and deservedly respected member, Richard Hart Davis, had been selected to fight the battle of anti-reform, but on his canvass he found the cause hopeless, and on the 30th he wisely retired. On the 15th of September Mr. Charle Pinney was chosen mayor, and George Bengough and Joseph Lax sheriffs. On the 19th of September the bill was finally carried in the Commons by 345 votes to 239 but after a powerful debate in the House of Lords which lasted from October 2nd to October 7th, it was thrown out by a majority of 41 upon the second reading. Only two bishops voted for the bill, while twenty-one, including the primate (exactly the number that would have turned the scale), voted against it. This made the prelates highly unpopular, and for a while was certainly very injurious to their order. At Radical meetings the abolition of the House of Lords was advocated, whilst those who could not agree to so extreme a measure were perfectly willing to exclude the bishops from all legislative power.

On October 12th 60,000 persons walked in procession to St. James’ palace, London, to present an address to the king. These were joined by a rabble who demolished the windows of unpopular peers, and committed still grosser outrages. A similar riot broke out at Derby, where their excesses culminated in the breaking open of the Borough gaol and the release of the prisoners. In an attempt on the County gaol they were less successful; they were fired on and several of the rioters were killed and others wounded. At Nottingham a mob attacked and burnt the Castle: from thence they marched against the country seats of the anti-reform peers and gentry, several of which they sacked and pillaged. Upon that Sir Charles Wetherell. in the House of Commons, attacked Lord Althorp and Lord John Russell, and charged them with conniving at the dastardly attacks that had been made on the anti-reformers, and with encouraging illegal combinations as a means of carrying the Reform Bill. This added greatly to his unpopularity. Such a state of excitement throughout the kingdom had never before been known. Political unions had been formed in moat of the large cities; meetings of 150,000 persons had been held, for reform, and the country, when, on the 20th of October, Parliament was prorogued, was within a measurable distance of civil war.

On the rejection of the Reform Bill by the lords, sundry meetings had been called in Bristol by the party of progress, which were numerously attended; by permission of the mayor, Mr. Charles Pinney, on October 12th, one such was held in the Guildhall, from which it was adjourned to Queen square; the chair was taken by Mr. J. Addington; the chief speakers were Messrs. R. Ash, J. E. Lunel, Jos. Reynolds, J. Manchee, E. Protheroe, M.P., C. H. Fripp, Rev. Francis Edgeworth (Roman Catholic), John Hare, W. Herapath, Dr. Carpenter and Captain Hodges. The speeches were undoubtedly strong, especially those of Mr. Protheroe and Captain Hodges; so also were the resolutions, which, together with a loyal address to the king, were passed unanimously by acclamation. On the other hand, the Tories, elated by their victory in the House of Lords, were unsparing in their taunts and defiance.

Meanwhile the day of the crucial test drew near, and, on October 18th, a meeting was called by Captain Claxton and sundry others (chiefly captains in the West India trade) of sailors; it was held on the decks of the Earl of Liverpool and an adjoining ship, the Charles, ostensibly for the purpose of voting a loyal address to the sailor king (this was the only reason given in the requisition); the real object, however, was to get the sailors to form a body guard to protect Sir Charles Wetherell. This was frustrated by Mr. John Wesley Hall and other reformers, upon which Captain Claxton (who was in the employ of the corporation as corn-meter) declared the meeting dissolved. It was reconstituted immediately upon the Quay; Mr. Hall was installed as chairman, and the following resolution was moved by Mr. J. G. Powell, and seconded by Mr. Webb :

That the sailors of this port on the present occasion earnestly express their decided and loyal attachment to his majesty and his Government, but will not allow themselves to be made a cat’s paw of by the corporation or their paid agents.

As the day for holding the assizes drew near, great apprehensions arose with regard to the safety of the recorder’s person and the peace of the city, and the magistrates, by deputation, submitted to him the propriety of postponing if possible, the gaol delivery. Sir Charles was afterwards accused of having persistently come down to exercise the functions of judge, contrary to the remonstrances of the Governement, as well as of the civic authorities — a statement which he averred to be, in every part of it, false, base and scandalous. The Government was certainly never consulted, and if they had been, the chancellor of the exchequer stated “that they knew the assizes could not have been legally held without the recorder’s presence;” whilst the magistrates simply consulted with Sir Charles as to the practicability of a postponement. On finding that the gaol must be delivered, the authorities, a week before the assize time, sent a deputation to Lord Melbourne, at the Home office, and requested the aid of a body of soldiers to keep the peace during the recorder’s visit. His lordship sought a conference with the members for the city; Mr. Baillie was from home, but Mr. Protheroe engaged to go down to Bristol and accompany Sir Charles in his carriage, if the military were dispensed with “His friends,” he said, ”would be answerable for order, if the people were allowed only to give expression to their strong and unalterable disapprobation of Sir Charles Wetherell’s political conduct; but,” he added, “he would not be answerable for the quiet of the city if the military was employed.” Mr. Herapath, president of the Political Union, who had been requested to induce the union to form a guard of protection for the recorder, on learning the application that had been made, informed Mr. Alderman Daniel that he had not been aware of the intention of the city authorities to employ an armed force for the protection of a judge of the land — a course which he believed to be unprecedented in English history, and which had produced an effect upon the council of the union which the magistrates alone must be answerable for. “However,” he added, “I feel confident that no member of the council will be found committing outrages on that day.” Whether these words were meant as a warning or as a menace, unhappily the expectation of outrages was fearfully fulfilled. “The scum that rises uppermost when the nation boils,” overpowered the men who had kindled the fire, and vain were all attempts of legal authority or of popular leaders to repress the tumult, or to confine it within moderate bounds.