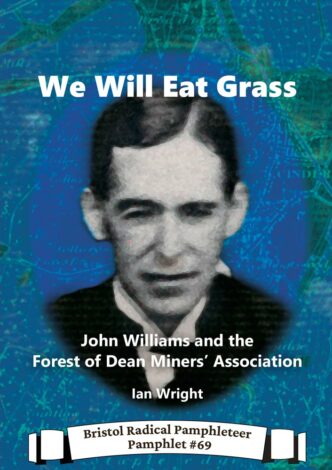

We Will Eat Grass by Ian Wright, published by the Bristol Radical History Group, is the story of John Williams, the Agent for the Forest of Dean Miners Association, through the turbulent times of the 1920s.

We Will Eat Grass, describes how Willams arrived in the Forest from his home in the Garw Valley in the coalfields of South Wales. He won the position as Agent for Forest miners just after the bitter lock-out of 1921 and faced a local association demoralised and in debt. He recruited new members and rebuilt the union.

Like many trade unionists at the time, Williams searched for political solutions to resolve the struggles of working people. Many believed in syndicalism in which trade union power would achieve change faster than the slow reforms promised by parliamentary politics. Influenced by the revolutionary events in Russia in 1917, Williams was drawn to the Communist-led movements that pushed for radical action to overthrow capitalism.

Ian Wright has put in a lot of work researching the life of John Williams during a time that has many echoes today. International capitalism was unable to sustain living standards for ordinary working people. Miners were vulnerable to the fluctuations of global coal prices. The industry was fragmented amongst thousands of mine owners who competed against each other , keeping prices down but collaborating to suppress wages.

Ian highlights the hazards of mining by featuring the deaths of miners as the story of the 1920s unfolds. He also describes how the Forest miners were amongst the lowest paid in the country.

Despite his sympathies for communism, Williams worked hard for the Labour Party and his arrival reinforced the move away from the Liberals in the Forest. The radical Liberal MP, Charles Dilke had been a firm supporter of miners but his successor was a mine owner. The shift in political favour in the Forest was secured when James Wignall was elected as the first Labour MP.

When Wignall collapsed and died in the House of Commons in 1925, Williams was nominated to replace him. But he didn’t see his career in parliament. Instead, Alf Purcell, the left-wing General Secretary of the French Polishers’ union and President of the Trades Union Congress (TUC), was selected and won the byelection to become a hard-working MP for the Forest of Dean. Purcell shared William’s political outlook and the two men became good friends. Purcell was a founding member of the British Communist Party and believed that parliament alone could not resolve the contradictions of capitalism.

In its 282 pages, We Will Eat Grass tells of the difficult period as the coal industry struggled to compete in the post-war world. Much like today, workers faced a long period where wages failed to keep pace with the cost of living and many groups were forced to accept pay cuts.

Many on the left at that time believed that revolutionary change would be triggered by a general strike – a few still do! Every annual Trade Union Congress has a group outside the entrance shouting, “TUC get off your knees, call a general strike”.

Williams believed that coordinated strike action was the only hope to stop pay cuts or longer hours for miners. Convincing one group of workers to stop work on behalf of another group is hard. As MP, Purcell may have shared that hope in solidarity action but as TUC President, he would also have known that the federation was established to coordinate the views of the hundreds of different unions but not be the central command.

In 1925 the ’Tipple Alliance’ of mining, rail and transport unions held firm and forced the government to offer the coal industry temporary subsidies rather than see pay cuts but this only delayed the crisis until May 1926. The government prepared for the general strike by stockpiling coal stocks and mobilising forces that could maintain the wider economy and control order.

Forest of Dean miners supported the clarion call of ‘Not a penny off the pay, not a minute on the day’. But when unions threw themselves into the 1926 General Strike this proved to be a hard line that allowed no room for a negotiated settlement.

When the employers locked out miners who refused to accept pay cuts, the nine-day strike began.

We Will Eat Grass doesn’t try to explain why the strike was called off. The government sensed victory and refused to negotiate, leaving the TUC to call off the action. It was a bitter blow and must have tested the friendship between Williams, shocked at the betrayal and Purcell, who was part of the TUC decision to stop the strike.

The book describes how miners fought on alone for another six months. Williams led attempts to stop miners from going back to work. The tradition of small free mining proved a problem as many continued to operate. There were clashes between pickets and strike breakers, with mounted police brought in to control order. As in 1921, Forest miners refused to be bowed – living up to the title of the book based on a quote made at the time that they would eat grass before giving in. But the union accepted defeat and left local districts to negotiate deals the best that they could.

Purcell did his best to support the striking miners and gave his time and money generously. The Forest miners maintained their support for him but he opted not to stand in the 1929 General Election and returned to his home in Manchester.

Without the threat of strike action, Williams became an expert at using legal means to win results and compensation for miners and their families. His belief that a better world was possible must have been sorely tested through these years. He remained steadfast in his work until his retirement in 1953 – more of his story is promised to come from Ian.

With the detail he has given in We Will Eat Grass I look forward to the next edition.