Just over a year ago a project was launched to research, design and install a ‘corrective’ plaque on the statue of Edward Colston in Bristol City Centre. It was claimed by the originator of the idea, Bristol City Council’s Principal Historic Environment Officer, that the new version was needed to stop the statue being damaged by unauthorised ‘protest plaques’. Several of these have been fixed to the statue over the last couple of years and removed by Bristol City Council. It appeared the main reason for the ‘corrective’ plaque was to expose the hidden histories of Edward Colston, including his leading role in organising the seventeenth century slave trade and his political and religious bigotry which made his ‘charity’ fundamentally selective. These historical facts had been deliberately obscured over the last couple of hundred years by the celebration, commemoration and memorialisation of him as ‘Bristol’s greatest philanthropist’ and as is stated on his statue, “one of the most virtuous and wise sons of their city”.[ 1 ]

From the very beginning the project was vague and had been tacked onto a wider educational scheme associated with Colston Primary School (now Cotham Gardens Primary School) who had recently engaged in extensive consultations with parents, pupils and teachers to change the name of the school.[ 2 ] The proposal for the plaque project carried several warning signs. It was claimed that pupils from Cotham Gardens would develop the concepts to go on the plaque by interviewing “a selection of visitors who have an informed opinion and vested interest in shaping the information to appear on Colston’s statue”.[ 3 ] These initially included several members of the Society of Merchant Venturers (SMV) including Francis Greenacre and Anthony Brown who have consistently defended the “toxic brand” of Colston over the last few years.

Dr Madge Dresser, an historian of the slave-trade in Bristol, was employed by the project to draft the words for the plaque. This begged the question as to whose views and which histories were going to be represented on the plaque; Dresser’s?… the pupils at Cotham Gardens?… the selection of “visitors who have an informed opinion”? … the project managers in Bristol City Council? … or perhaps the SMVs? Rather than the transparency which this controversial project needed, we were left with a lack of clarity about who was deciding what went on the plaque, informal meetings and a consultation process that took place on an obscure Council Planning website.

As one of the historians who has been researching the history of Edward Colston over the last few years, I was informally consulted over some of the historical facts surrounding his life. Over a few months I became aware that the proposed drafts were changing from a brief description of the uncomfortable histories of the slave-trader towards a more sanitised, pro-Colston version, cheerleading his philanthropy (which is well-known in any case). These changes were mainly due to the intervention in the project of Francis Greenacre, a member of the SMVs who has become the de facto historian for the organisation. Greenacre and his supporters worked hard on the project organisers to alter the plaque’s wording, despite the veracity of the history. It appears their primary motive was to protect the Colston brand and by default the reputation of the SMVs. So what went on the plaque, what was taken off, what was added and what should have been on there?

What went on the plaque…

The original wording of the ‘corrective’ plaque in June 2018 read:

From 1680-1692, Bristol-born merchant, Edward Colston was a high official of the Royal African Company which had the monopoly on the British slave trade until 1698.[ 4 ] Colston played an active role in the enslavement of over 84,000 Africans (including 12,000 children) of whom over 19,000 died en route to the Caribbean and America.[ 5 ] He also invested in the Spanish slave trade[ 6 ] and in slave-produced sugar.[ 7 ] Much of his fortune was made from slavery and as Tory MP for Bristol (1710-1713), he defended the city’s ’right’ to trade in enslaved Africans.[ 8 ]

Local people who did not subscribe to his religious and political beliefs were not permitted to benefit from his charities.

All of these historical facts are backed by evidence from primary sources. Soon after this draft was created, it was added that Edward Colston, like his father before him, had become a member of the Society of Merchant Venturers.[ 9 ]

What was taken off…

The first thing to go from this draft was that Edward Colston was a Tory. The pro-Colston lobby initially argued that this wasn’t true, despite the fact that Edward Colston appears on the ‘Hanover list’ of MP affiliations as a Tory in 1710, the year of his election to Parliament.[ 10 ] In fact, Colston was the first Bristol MP to declare himself a Tory. Several members of the Conservative Party then objected to having Colston’s political affiliation on the plaque and it was removed.[ 11 ] Next, the statement that as an MP Edward Colston defended the right of Bristol merchants to trade in enslaved Africans was expurgated despite its truth.[ 12 ] Having removed this uncomfortable fact, Colston’s role as a Bristol MP was instead turned into a positive statement in the draft! Next to go was Colston’s involvement in the Spanish slave trade. Greenacre was unaware of Colston’s huge investments and role as a commissioner in the South Sea Company mainly because they reside in primary sources in Hoare’s Bank in London and have not (yet) been reproduced in history books.[ 13 ] So Greenacre claimed that this was also not true, and soon after it was removed from the draft; it was said at the time because of “lack of space”.

Another glaring issue for Colston apologists was his involvement in the Society of Merchant Venturers (SMVs). As a member of the SMVs, and perhaps now working for them as ‘history point man’, Greenacre was keen to remove any connection between Colston and this elite Bristol businessmen’s (sic) club. This he achieved by arguing that:

He [Edward Colston] attended only two meetings of the Society [of Merchant Venturers] over 38 years and it was certainly not ‘as a member’ that he submitted petitions to parliament, but as an MP.[ 14 ]

So although Colston had been a member of the SMVs for 38 years, according to Greenacre this did not really ‘count’. He also claimed that there was no connection between being a member of the SMVs and pushing forward their demands as an MP, something which most historians of the period would find laughable. Another obvious contradiction concerns Colston’s charitable relationship with the SMVs and his donations and endowments. If his link with the organisation was so tenuous, why was it he entrusted them to oversee his schools, alms-houses and donations to the church during and after his death? After all, this is one of the main reasons Colston is still celebrated today by the SMVs. However, true to form, the link between Colston and the SMVs was severed by the project organisers and the wording altered.

Greenacre then moved onto the difficult issue of the statistics concerning the huge numbers of enslaved African men, women and children that were transported on Royal African Company (RAC) ships and Colston’s direct involvement in this. This was a real problem; either Colston’s role in all this human suffering had to be reduced or the figures had to be taken off the plaque somehow. It was difficult to denigrate Colston’s position in the RAC as he had been a manager in the organisation for nearly ten years, sat on almost all the management committees and then became its second in command, the Deputy Governor. Arguments that he was ‘just doing his job’ weren’t going to cut it here. Nevertheless the word ‘high official’ was reduced to merely ‘official’, suggesting Colston was just an ‘operative’ rather than a deputy chief executive. Similarly, the fact that the RAC had been the sole organisation running the British slave trade in the mid to late seventeenth century was problematic. There had been no free for all, like in the eighteenth century, where supposedly ‘everyone was at it’; something the SMVs have used as a defence in the past for the role of their organisation in slavery.[ 15 ] So the reference to ‘monopoly’ was deleted ‘to reduce the word count’.[ 16 ]

Greenacre attacked the problem of the horrific statistics in a more subtle way. Initially he argued that the part of the draft stating “(including 12,000 children)” was clumsy use of parentheses and should be removed for this reason. This initially failed, so then he started to attack the definition of ‘children’:

The earlier reference to 12,000 children has now become ‘12,000 children under 10’. Even Roger Ball of Bristol Radical History Group has written that children were ‘loosely defined as being of ten years or younger’ and the definitions were still more arbitrary, various and complex than that. Such casual misinformation undermines the value of these horrific statistics.[ 17 ]

This is an odd argument. It is basically saying because we are not exactly sure that all the enslaved African children transported on the RAC slave ships were 10 years of age or less we should ignore them! You may also have noticed something else that is strange. The original statistics took a conservative, contextual position, defining ‘children’ on the basis of seventeenth century slave-trading (i.e. ten years or less). If I had taken today’s definition of under-16 as a ‘child’ or ‘minor’ the numbers of children on RAC ships would have been inflated far above 12,000.[ 18 ] In any case, Greenacre managed to convince the project managers to remove the numbers of enslaved African children from the wording. However, at this point we must give some credit to the project managers. Despite the pressure to take all the statistics off the plaque, they resisted. After all, at this rate of removal there would have been merely a vague reference to the trans-Atlantic slave trade by the time the plaque actually got on the statue. But Greenacre was not finished yet, as one serious problem remained.

This was Colston’s religious and political bigotry, which is well documented as he was explicit in life and after his death about who was to benefit from his charity. Simply put, nothing was to go to anyone who deviated from his strict religious doctrines or allowed non-Church of England believers to partake. This excluded huge numbers of Bristolians; Catholics, Jews, non-conformists (Quakers, Baptists) and other religious groups, as well as progressive ministers within the Church of England. This was not a passing phase; Colston was clear about this throughout his life and systematic in asserting these draconian rules in his will. In fact it is hard to find any charitable donations by him which do not carry orthodox religious caveats that exclude dissenters, Catholics and many others. Colston was quite clear that he would even take clothes and food away from children if this turned out to be the case. This is problematic when you are trying to mythologise Colston as a kindly philanthropist, unreservedly ‘giving to the city of Bristol’. So these words in the draft…

Local people who did not subscribe to his religious and political beliefs were not permitted to benefit from his charities.

…just had to be deleted; which they were. Now that most of the uncomfortable stuff on Colston had gone, the time was right for Greenacre and his supporters to start rebuilding Colston’s reputation.

What was added…

You may remember at the start of this article that the plaque was originally described as being ‘corrective’, on the basis that it would be adding hidden histories of Edward Colston to the dominant narrative of him as a ‘great philanthropist’ who ‘gave so much to the city’ represented by his statue. So I was amazed to find, when I came across the opening paragraph of the final version of the plaque, these words:

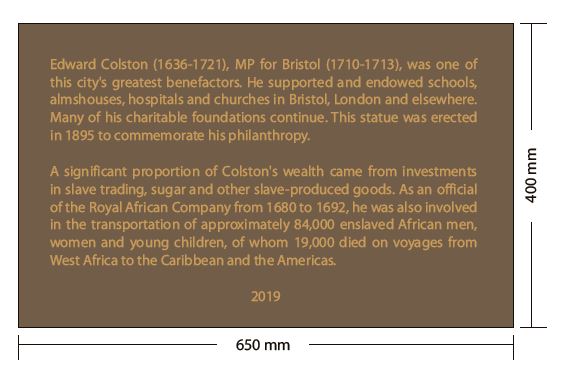

Edward Colston (1636-1721), MP for Bristol (1710-1713), was one of this city’s greatest benefactors. He supported and endowed schools, alms-houses, hospitals and churches in Bristol, London and elsewhere. Many of his charitable foundations continue. This statue was erected in 1895 to commemorate his philanthropy.

It was almost as if the plaque had become ‘un-corrective’; it was telling the same old story. The hidden history of religious and political bigotry had vanished, as had defending and propagating the slave trade. Colston was back again on his pedestal as the ‘great philanthropist’, the ‘lover of humanity’ and of ‘the poor’, who was giving to us grateful Bristolians even today. It was almost as if the money had fallen from heaven as a gift from God, rather than being made off the back of selling human beings, the labour of maritime workers and money lending. It felt like the first paragraph told the ‘real’ story of Colston, and what followed was just an unfortunate afterthought:

A significant proportion of Colston’s wealth came from investments in slave trading, sugar and other slave-produced goods. As an official of the Royal African Company from 1680 to 1692, he was also involved in the transportation of approximately 84,000 enslaved African men, women and young children, of whom 19,000 died on voyages from West Africa to the Caribbean and the Americas.[ 19 ]

What should have been on there…

There are many histories of Edward Colston’s religious bigotry, his financial affairs and his political dealings that are yet to be told. Research by members of Bristol Radical History Group is demonstrating Colston’s close links with the Hoare banking family and insider dealing in the slave-trading South Sea Company, exposing the myths about his benefactions, documenting the diverse ways he made money in the Royal African Company and the contradictions and corruption in his involvement in the Society of Merchant Venturers. However, amongst all this we must not lose sight of the immense suffering which Colston helped organise and propagate through his involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. Until this is faced up to by his apologists we will continue to see arguments about ‘balance’. As we said in 2015 to representatives of Bristol Cathedral, how can you balance the deaths and enslavement tens of thousands of African men, women and children with so-called ‘philanthropy’? The so-called ‘corrective’ plaque should go into the dustbin and the statue into a museum so in the future our children can study the folly of the Colston apologists.

- [ 1 ] For the myths that surround Edward Colston and his statue see Ball, R. Myths within myths… Edward Colston and that statue Bristol Radical History Group, 14 October 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.brh.org.uk/site/articles/myths-within-myths/ [back…]

- [ 2 ] The new name, Cotham Gardens Primary School, was announced in December 2017: Yong, M. “Colston’s Primary School makes decision on removing controversial slave trader’s name” Bristol Post December 1, 2017 https://www.bristolpost.co.uk/news/bristol-news/colstons-primary-school-makes-decision-864514 [back…]

- [ 3 ] Colston Primary – Heritage Schools Local Learning – Celebrating 70 years, Myers-Insole Local Learning Community Interest Company, March 2018. [back…]

- [ 4 ] For Colston’s involvement in the Royal African Company see: Ball, R. Edward Colston Research Paper #2: The Royal African Company and Edward Colston (1680-92) Bristol Radical History Group, 17 June 2017 https://www.brh.org.uk/site/articles/edward-colston-research-paper-2/ [back…]

- [ 5 ] For the statistics see: Ball, R. Edward Colston Research Paper #1: Calculating the number of enslaved Africans transported by the Royal African Company during Edward Colston’s involvement (1680-92) Bristol Radical History Group , 1 May 2017. Retrieved from https://www.brh.org.uk/site/articles/edward-colston-research-paper-1/ [back…]

- [ 6 ] Colston’s involvement as a commissioner and investor in the South Sea Company (SSC) whose primary business was trading enslaved Africans with Spanish possessions in South America is the subject of a pending research paper. Analyses of Colston’s accounts in Hoare’s bank in London show he had significant investments in the company. By mid-1719, Colston’s stock holdings in the SSC had increased to £7,840 and he was racking in £470 in dividends each year. This was a large amount of money, the base sum worth more than £19 million and the dividends alone more than £1 million in 2016 (by GDP per capita conversion). In comparison, Edward Colston left £2,440 in his will to schools, almshouses and churches in Bristol. [back…]

- [ 7 ] Wilkins, H. J. Edward Colston (1636-1721 A.D.), a Chronological Account of His Life and Work Together with an Account of the Colston Societies and Memorials in Bristol (Bristol: Arrowsmith, 1920) p. 49. [back…]

- [ 8 ] Morgan K., Edward Colston and Bristol (Bristol: Bristol Branch of the Historical Association, 1999) p. 13. [back…]

- [ 9 ] Edward Colston lent £1,800 at 5% interest to the Bristol Corporation in 1682 (this was equivalent to, per capita GDP, £11.7 million in 2016). In December 1683, he was made a free burgess of the city. A week later was declared to be a ‘mere merchant’ and elected as a member of the Society of Merchant Venturers. The ‘freeman’ status gave him the right to trade in Bristol. A happy series of coincidences! Ball, Edward Colston Research Paper #2. [back…]

- [ 10 ] Colston was classified as a Tory in the ‘Hanover List’ of 1710 which defined “Tories, Whigs, and those doubtful”: Appendix XXVI: Contemporary lists of Members. Published in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1690-1715, ed. D. Hayton, E. Cruickshanks, S. Handley, 2002; Hanham, A. COLSTON, Edward II (1636-1721), of Mortlake, Surr. Published in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1690-1715, ed. D. Hayton, E. Cruickshanks, S. Handley, 2002 [back…]

- [ 11 ] E-mail to author from Myers-Insole Local Learning Community Interest, Company 27 March, 2019. [back…]

- [ 12 ] Greenacre, F. Comments for Planning Application 18/03688/LA 26 October 2018. [back…]

- [ 13 ] C. Hoare & Co Archive, Edward Colston (1719), Customer ledger/folio no. F369. There is also evidence in Bristol. Two manuscript authorisations from Edward Colston to make payments from the dividends on £7,000 of his stock in the South Sea Company are held at Bristol Archives Ref. 42198/6/1. [back…]

- [ 14 ] Greenacre, F. Comments for Planning Application 18/03688/LA 26 October 2018. [back…]

- [ 15 ] In 2006 D’Arcy Parkes speaking on behalf of the SMVs made the following statement to the Bristol Evening Post: “We all regret that the slave trade happened. Slavery was a trade in which all of Bristol was involved in, but we believe an apology is totally meaningless.” Bristol Evening Post 28 November 2006. [back…]

- [ 16 ] Greenacre, Comments for Planning Application 18/03688/LA. [back…]

- [ 17 ] Greenacre, Comments for Planning Application 18/03688/LA. [back…]

- [ 18 ] It is interesting to note that the several thousand enslaved children that died on RAC slave-ships during Colston’s management did not appear on the plaque in the first place. A glaring omission in this author’s opinion. [back…]

- [ 19 ] Colston Statue Bronze Plaque Wards of Bristol, 19 December 2018. [back…]

Alan Rogers

Superb work by Roger Ball. Scholarly, concise, forensic and penetrating.

The pathetic attempt to minimize the involvement of the commercial and religious establishment of 17th and 18th century is exposed in all its dishonest detail.