‘Alas when our relatives and neighbours came to welcome us, whole we were embracing them and in the midst of our kisses, we, who carried the arrows of death were constrained to give them the poison, so that when they returned home, soon whole families were infected and in less than three days succumbed to the attacks’.[ 1 ]

Although there appears to be very few primary sources recounting the consequences and changes inflicted upon the population of Bristol during the era of the Black Death[ 2 ] a few rare manuscripts of the time have survived. I am drawing particularly on the work of C. E. Boucher The Black Death in Bristol, written in 1938 due to his extensive research and insight into rare manuscripts relating to Bristol. I am writing this during university library closures, one of the many impacts of the coronavirus disease pandemic of 2020,[ 3 ] thereby solely relying on e-sources. However, despite this limitation I still think it is worth a review of how the Black Death pandemic of 1348-49 caused far reaching socioeconomic and political change for the people of Bristol and the surrounding area.

Up until 2020, in the developed world, phrases such as plague, pestilence and famine are words that appear in a far distant, often romanticised past even though new pandemics over the last twenty years have given rise to near misses in Europe. Even once common diseases such as diphtheria, cholera and smallpox seem an age away now. This has come about purely because of the introduction of mass immunisation in 1942. Tuberculosis, an illness of crowding and poverty is now extremely rare as most humans are immunised against this killer disease. Yet today as I write, in March 2020, in Europe and across the world, we find ourselves and our governments once again facing up to the far-reaching realities of the sheer speed and disruption, both economic, and social, that Covid-19 is spreading through our societies.

Our distant ancestors who lived during the fourteenth century knew only too well about self-isolation, food shortages, no cure or immunisation, and how quickly a highly contagious disease had the potential to stagnate an economy already in crisis due to climate change and consequently failed harvests.[ 4 ] People lived a mostly rural life in small villages which offered only a vulnerable and precarious hand to mouth existence in the best of times. It is known that nine out of ten people worked on the land before the Black Death. However, for the population living in port towns such as Bristol, life was to undergo a dramatic shift of economic alignment. Bristol was the first city in England to be affected by the Black Death. It is estimated by some historians that the population of Bristol in 1347 was around 10,000 but by others to have been between 15,000 to 20,000, meaning that no one is exactly sure. At this time Bristol was the third largest town in England although after the Black Death pandemic the population of England as a whole is estimated to have returned to its level in 1100. It is widely believed that nationwide the population was approximately 5 million in the year 1300 and by 1400 it was reduced to around 2.5 million; it was not until 1630 that the population again reached 5 million.[ 5 ] The study English Medieval Population: reconciling time series and cross sectional evidence reviewed the main cross-sectional mass of population and time-series evidence based on manorial returns. The authors calculated that the population declined from 4.81 million in 1348, to 2.60 million by 1351, an average reduction of 48 per cent.[ 6 ] The fall in population during and following the Black Death was catastrophic.

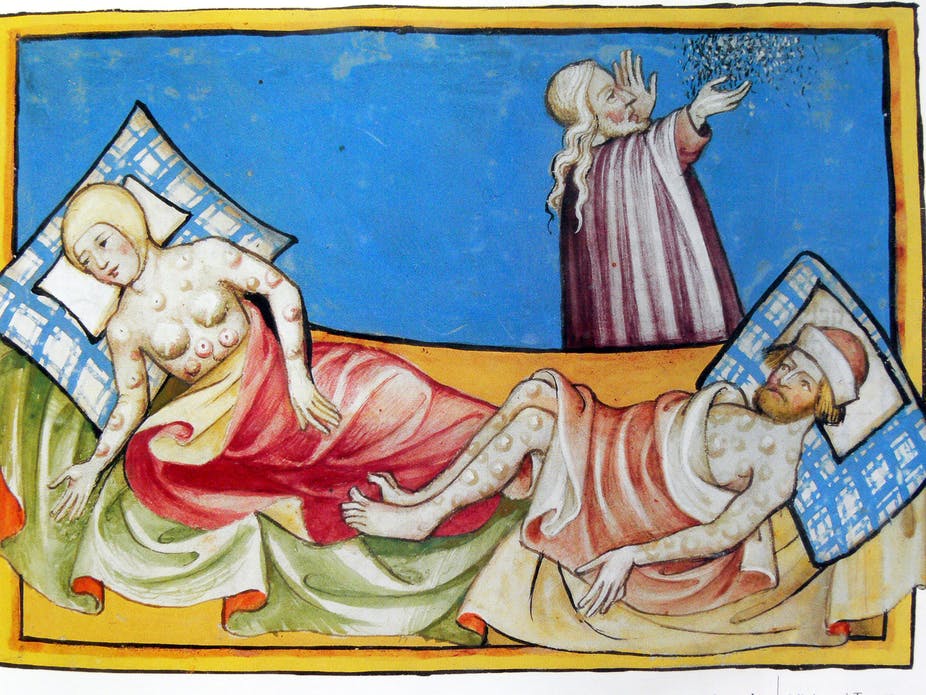

Life in Bristol in the fourteenth century comprised of people living in high density conditions, far greater than today. People lived in small crowded homes on narrow streets, with no sanitation, little ventilation and in smoke filled rooms. The streets were open sewers, with nothing other than holes in the ground for solid waste which would have contaminated the water wells. Rats and other vermin would have been impossible to control with the added factor of vermin running off the boats moored in the harbour. It is widely known that the plagues that beset England in the fourteenth century (there were at least eight), came in through the southern ports of England; Dorset and Somerset are recorded by monks at the time to have been stricken by the plague. Therefore, we can conclude that Bristol port would have been no exception.

An account from the time testifies that in 1348, in Melcombe, Dorset and just before the Feast of St John the Baptist (held 24 June), two ships were moored alongside, one of them being from Bristol. Apparently one of the sailors had brought with him from Gascony the plague: ‘the seeds of the terrible pestilence…the men of that town of Melcombe were the first in England to be infected’.[ 7 ]

It is believed that the first deaths occurred in Bristol a few weeks later on the Feast of the Assumption on 15 August, 1348. Knighton, Canon of Leicester, wrote that when the plague came to Bristol ‘there died as it were the whole strength [manhood] of the town, taken in sudden death, for there were few who kept their beds for more than three days or two days and a half’.[ 8 ]

Samuel Seyer, in his memoirs provides a vivid quote from a Calendars of Bristol.

‘In 1348 the plague raged to such a degree in Bristol that the living were scarcely able to bury the dead. The Gloucestershire men would not suffer the Bristow men have any access to the, them. At last it reached Gloucester, Oxford and London; scarce the tenth person was left alive, male or female. The churchyards were not large enough to bury the dead and other places were appointed. At this period grass grew several inches high in High Street and Broad Street; it raged chiefly in the center [sic] of the City.’[ 9 ]

In the Patent Roll for 15 November, 1349 the Crown granted the ‘good men’ and parishioners of St Cross the Temple, Redcliffe, Bristol a pardon for acquiring from the Prior of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem half an acre of land to expand the churchyard because it had been filled up with bodies buried during the pestilence. It would appear from such accounts that Bristol was very badly affected with the possibility in a worst case scenario of up to only one tenth of the population surviving according to accounts written from other parts of the country. Geoffrey the Baker wrote at the time saying that ‘scarcely a tenth of the adult population of Bristol survived’.[ 10 ]

Such dramatic changes in the vitality and social relationships in a city like Bristol would have disabled commerce for the merchant classes and also for the ordinary people residing in the port of Bristol. Huge social upheaval was inevitable as the survivors realised that the traditional feudal system could not continue as it was before the pandemic. The feudal system had failed to protect the common people and religion has failed to save them from an early death. There is much evidence to suggest that the nobility, high clergy and wealthier classes were able to transport their households out of the cities to their country estates in order to avoid becoming infected as we see happening during this current pandemic. These actions and consequences raised new questions by the peasantry: Who really held the power now in both the economic and political sphere?

The Black Death bought about an immense shortage of labour in the towns and countryside alike. It is estimated that more than thirteen hundred to three thousand English villages alone vanished between 1350 and 1500 directly due to numerous plagues. But what is not known is how many succumbed due to death as opposed to migration into the towns. As the pandemic spread towards the city of Gloucester the town council were horrified at the magnitude that had befallen their neighbours in Bristol. An embargo was placed on all communication between the two cities with the gates of Gloucester closed to any refugees, in vain, to halt the spread of the disease. Many citizens were also said to have fled the town to seek the protection of the countryside. As a result, legislation was brought in to fine for each day of absence any person found to be leaving the city.[ 11 ] This action was of course ineffective due to rats that lived in the ditches and on the river boats that sailed the course of the Severn.[ 12 ] There is no evidence that Bristol also brought in similar emergency laws, but it might have very well been the case.

Although Boucher states that ‘records are largely silent about the plague and its effects on the life of the town’ [Bristol] he exhaustively studied manuscripts from the medieval period. His research led him to conclude that it was evident that Bristol faced problems with movement of people migrating into the town from the countryside thereby placing stress on the pre-existing traditional craft and merchant guilds of which there were twenty in the City. Guilds’ had monopoly over trade and end product value which inevitably led to conflict when their markets began suddenly collapsing. They found it almost impossible to adjust due the fast moving pace of the pandemic. In additional to this their wholesalers were decimated too, leading to inflation. New arrivals of crafts people occupying available empty premises were quickly able to launch new trading markets bypassing guilds: The traditional guilds were outpaced by social and economic change.

Farming practices at the time relied on cheap labour or bonded labour in the case of serfdom. Taxes were usually paid in goods, such as with a chicken, eggs or barley perhaps. Much of the old field system was laid to waste due to lack of people to work the land and due to a prolonged change in the climate that resulted in no less than ten years of failed harvests preceding 1348. As profits fell the Crown was forced to offer tax breaks to landowners across the country. Boucher cites the example of Guy de Braine who on 20 November, 1349 obtained a reduction of £30 from the taxation demand of £120 reserved to the King, ‘in consideration, of the great diminution in the issues of profits on the castle of St. Briavels and the Forest of Dean on account of the present pestilence’.

The traditional way for a man or women to earn his place in a guild was through a long process (up to 12 years) of apprenticeship, with a final year spent as a journeyman. The system operated in part to guarantee both the continued quality of goods and to provide a cheap labour source for business owners. This control also had an institutional social function in that the practice was upheld within families with sons or son in laws also being able to join. This ‘middle class’ or ‘middling sort’ utilised structural impediments to block ambitious commoners from joining guilds. However, the new class of free peasantry entering the town had little regard for the closed shop mentality of medieval guild structures. Masters were being lost prematurely to the pestilence the consequence of which was that their sons were to take over the established businesses, often with little experience. At the same time apprenticeships were being shortened to fast track skilled craftspeople, however many found that they were unable to become masters of their trade without a family connection. Taking advantage of the disarray in the traditional guilds a new army of urban wage earners set up shop quickly and used their skills to craft much needed objects and food stuffs to be sold directly to the public for cash, thereby becoming new traders, in their own right. Some peasants were even now in a position to acquire property for the first time, but they were still denied membership of guilds. Women were also now barred from the guilds in order to reduce competition. A revolutionary seismic change to the status quo for the ‘middling sort’ of Bristol had occurred: The traditional merchant and craft guilds were being bypassed and undercut. The Black Death had swung the balance in favour of a new class of the landless with the period becoming known as the “golden age” of the English peasantry.

To understand further what was occurring in Bristol we need to examine the outlying rural population and the consequences of the Black Death on those who farmed the land. More primary evidence has survived regarding the rural population, probably due to literate priests working in these areas in connection with monastic lands.

Due to the high death toll and a critical shortage of labour rural workers and the remaining able bodied workers had been able to secure higher wages. Crucially, for the first time it is believed serfs were paid in cash. It is estimated that wages in England rose between twenty eight percent from 1340 to 1350 and twenty to forty percent from the 1340s to the 1360s. For example, in Cuxham, Oxfordshire, a free lancing ploughman earning 2 shillings a week before the plague (although this payment was likely to have been made in goods), was able to earn 3 shillings in 1349 and 10 shillings in 1350.[ 13 ] This is a percentage rise in real wages from 1347 to 1350 of five hundred percent. Such wage rises must have parallels with those that dwelt in the towns too, if not at an even higher rate. It is important to remember that death rates were higher in the towns due to density of population, thereby decimating the skilled workforce to an even greater extent.

As the middling sort witnessed profits tumble the Crown sought to mitigate against disquiet and panic due to the upheavals caused by the sudden and high death rate. The Crown under pressure from lords, masters, the church and guilds brought in emergency economic powers hoping to stabilise not only the economy but also in fear of further peasant uprisings. (There had already been several peasant revolts across England). It was hoped that these measures would reassure masters and the elite classes alike that social order would return and bring some form of normality back to their previous status as the controlling power over peasants.

First came the Ordinance of Labourers in 1349 followed by the Statue of Labourers in 1351. Both these laws called for a return to the wages and terms of employment before the Black Death, being set at the average wage during 1346. According to Routt with ‘robust enforcement they did succeed in slowing wage increases for a short time’. This was the beginning of English labour law. The measures included a ban on wage increases and a requirement that every person under the age of 60 within the workforce to suffer restrictions on movement in search of work. Women were to be restricted the greatest. With a labour scarcity many new opportunities should have opened up for women. In reality the evidence suggests that the new regulations only ‘added to their geographical and occupational immobility, pressing them into accepting permanent service contracts and inhibiting their ability to work casually by the day’. (Day and casual workers received higher wages particularly during the harvest). Low wages appeared to actually continue among annual workers with women less able than men to profit from the economic gains of the Black Death.[ 14 ] However, for men the attempt to regulate the market by law failed because the population level continued to stagnate due to recurrent outbreaks of plague and wages continued to rise.

Eventually, on the 6 January, 1364 an ordinance was made before the Mayor of Bristol for a financial aid package for the estates of the master of the craft of the Cobblers:

‘as well nigh impoverished by the excessive price of their servants who are loath to attend in the said craft, unless they have too outrageous and excessive salary, contrary to the Statute of our Lord, the King and to the usages of the said town’.

The purpose of this ordinance was to fix the rate of wages and to fine any master who paid more. Also, that a master may only employ one man or labourer, although piecemeal work was to be allowed. Furthermore two inspectors were to be employed by the city to observe that the new rules were being adhered to.

In general urban authorities in the medieval period did not offer any initiative in coping strategies with regards to public health issues. This was partly because there was nothing they could do to prevent infection and because public health was not recognised as a responsibility of mayors and bailiffs ‘unless it was to do with the sale of rotten food stuffs’.[ 15 ]

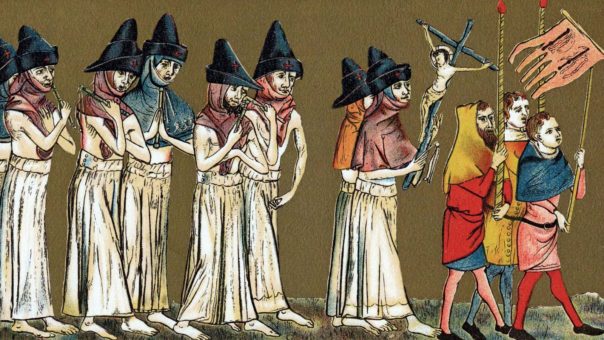

There would appear to be no evidence of rioting during the pandemic in Bristol, although there were food shortages in the years before the plague struck the city. It is likely that some of the better off people would have stored and hoarded food, particularly the wealthier classes who had the means to do so. However, many riots are recorded to have broken out in London during the Elizabethan plague years and many across Europe being directly attributed to the effects of plague. Fear and religious mania swept through the country with some believing it was God punishing his people for their sins, and with no cures charlatans were recorded selling herbal potions claiming they would give people protection.

In rural communities a new yeoman class began to demand fixed rents if not outright ownership of land with no service of duty to the lord of the manor. The English Peasants’ Rebellion of 1381 was partly due to the continuation and enforcement of the Ordinances and Statute of Labourers leading to both rural and urban dwellers being frustrated by the slow pace of legal change. Social order and hierarchy had changed with traditional socioeconomic manorial arrangements being broken down as labourers were enjoying higher wages and broader opportunities. It is widely held that the diets of labourers improved including more meat, fish, bread and ale. Although landlords struggled to find tenants for their lands, changes in forms of tenancy improved estate incomes through higher yields from the new tenant farmers.

Bristol was now moving into a new era of commerce, freer markets and early mercantilism with new opportunities for those that had been traditionally denied due to a subordinating class system. Where entrenched societal hierarchies were still in place there was a begrudging recognition of a new class of entrepreneurs rebuilding a broken economy but it took over a hundred years for society to adapt and recover both economically and politically. A new middle class of men (almost always men) emerged. These were people who were not born into the wealthy landed gentry but were able to to purchase plots of land, farms and homes in the city offering competitive rents to further residents. For example, in York by 1350 the number of newly acknowledged freemen (serfs no longer indentured to a wealthy lord) numbered 212.[ 16 ] The Black Death brought on dramatic change for the population of Bristol leading to a sudden increase in social mobility from the rural to the urban community.

The Black Death radically impacted a medieval society based on feudalism. Reappearances of the disease meant that by the 1370s England’s population had been halved. In Bristol the pandemic resulted eventually in new economic growth with the breakup of traditional aristocratic, master and guild monopolies. The sheer speed of the spread of the Black Death and its associated mortality gave the feudal economy no time to adjust and prepare. The ramifications of the Black Death were to continue well into the early sixteenth century.

- [ 1 ] Account taken from original Latin Gabriel de Mussis. Reprinted in Geschichte der Medicin und Epidemische Krauheneiten, Jean. 1882. As cited in C.E. Boucher. “The Black Death in Bristol”. 1938. Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. Vol. 60, pp.31-46. [back…]

- [ 2 ] Bubonic plague, a bacterial infection carried by fleas living on black rats living in merchant ships. It is likely that climate change also precipitated a population explosion among rodents hosting the disease, pushing them out of their natural habitat and into the proximity with humans – Sherman, 2007. pp.73-74. cited in J. Choonara. Socialism in a time of pandemics. International Socialism. Is.168. Posted 22 Mar. 2020. [back…]

- [ 3 ] Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) (SARS-CoV-2) is an infectious disease caused by a newly discovered coronavirus. [back…]

- [ 4 ] Research indicates that cool wet weather had lowered and dramatically reduced crop yields. The Climate Change Institute performed chemical analyses by extracting volcanic bits trapped in ice cores relating to the early 14th century. ‘Did famine worsen the Black Death’? Alvin Powell. The Harvard Gazette. 5 January, 2016. The full article can be found at news.harvard.edu/gazette [back…]

- [ 5 ] Mortimer, I. The Time Travellers Guide to Medieval England, 2008. [back…]

- [ 6 ] Broadberry, Campbell, Leeuwen. The fall during and following the Black Death was catastrophic. File: MedievalPopulation7. 27 July 2010. warwick.ac.uk. [back…]

- [ 7 ] 14th Century Chronicle from the Grey Friars at Lynn, ed. A. Grandsen, Eng. Hist. Rev., Vol. LXXII, 1957, p.2.74. Cited in P. Ziegler. The Black Death. Faber & Faber.2008. p.770. [back…]

- [ 8 ] Boucher. p.34 [back…]

- [ 9 ] Memoirs Historical and Topographical of Bristol, 1821-2. Vol. II, chap. Xv. P. 143. Cited in Boucher. p.34 [back…]

- [ 10 ] Boucher. p.34 [back…]

- [ 11 ] 14th and 15th Century Gloucester visit-gloucestershire.co.uk [back…]

- [ 12 ] Bubonic plague or Black Death is transmitted by a bacterium, the bacillus Yersinia Pestis. Fleas and rats participate in the process of transmission, and human beings usually become infected when bitten by a flea carrying the bacteria. There was also human to human transmission. [back…]

- [ 13 ] Routt, D. “The Economic Impact of the Black Death”. EH.Net Encyclopaedia, edited by Robert Whaples. July 20, 2008. [back…]

- [ 14 ] J. Humphries. ‘No, the Black Death did not create more jobs for women’. The Conversation. April 8, 2014. theconversation.com [back…]

- [ 15 ] Britnell, R. “The Black Death in English Towns.” Urban History 21, no. 2 (1994): 195-210. p.203. Accessed April 3, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/44613912. [back…]

- [ 16 ] Britnell, R. “The Black Death in English Towns.” Urban History 21, no. 2 (1994): 195-210. p.206. Accessed April 3, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/44613912. [back…]

Very good and interesting article – just one contention is regarding the emphasis on rats as a vector for The Black Death (vermin coming off ships, boats and the like). Recent research has called this into question, as no 14th C accounts of the plague mention rats dying en masse in public, as is known to occur in bubonic plague. Surely such a bizarre sight, even in a society used to rats, would have been recorded? Current theories are now tending towards the idea that on its path westwards from Asia the plague ceased to be infectious in form (through rat fleas), but rather took the pneumonic form, meaning it was spread from human to human via contagion (through breath), and thus became an invisible killer, even more terrifying to a culture that had no comprehension of microbes and viruses.

Thank you for your comment Kevin. As I mentioned in the footnotes some epidemiologists believe that human to human transference may also have taken place. However, this is only a theory. There is some evidence that more people died during hot weather in the summer, and this is when fleas are more active. On the other hand there was a very high mortality rate in the clergy who attended to the dying and dead, whereas the higher clergy mainly escaped infection. This would add weight to human contagion.