The centenary of the end of WW1 in 1918 will be widely commemorated across the country on Remembrance Sunday this year. However, the military style parades and ceremonies send a mixed message. On the one hand they are a moving display of mourning for the dead. On the other they tend towards a celebration of British military virtues, the heroic defeat of Germany and recent claims that WW1 was a ‘just’ or ‘necessary’ war.

The popular memory in the UK of an allied ‘victory’ in 1918 leaves many questions unanswered. Conservative military historians offer an explanation of this ‘victory’ citing the mass intervention of the US army, the superior morale, weapons and tactics of the British armed forces and some key battles in the summer of 1918. Though they remain curiously silent about the effect on morale of the Russian revolution, mass mutinies in the allied armies in 1917 and the collapse of Germany and Austria-Hungary into strikes and revolution at the rear and mass desertions at the front. The allied invasion of the Soviet Republic in 1918 gets hardly a mention, as do the strikes of hundreds of thousands of British servicemen in 1919 which helped bring the expedition to an ignominious end. How the end of WW1 was and is popularly remembered in Britain and Germany also provides clues to the ideological motivations of both conservative historians and nationalist politicians, journalists and commentators.

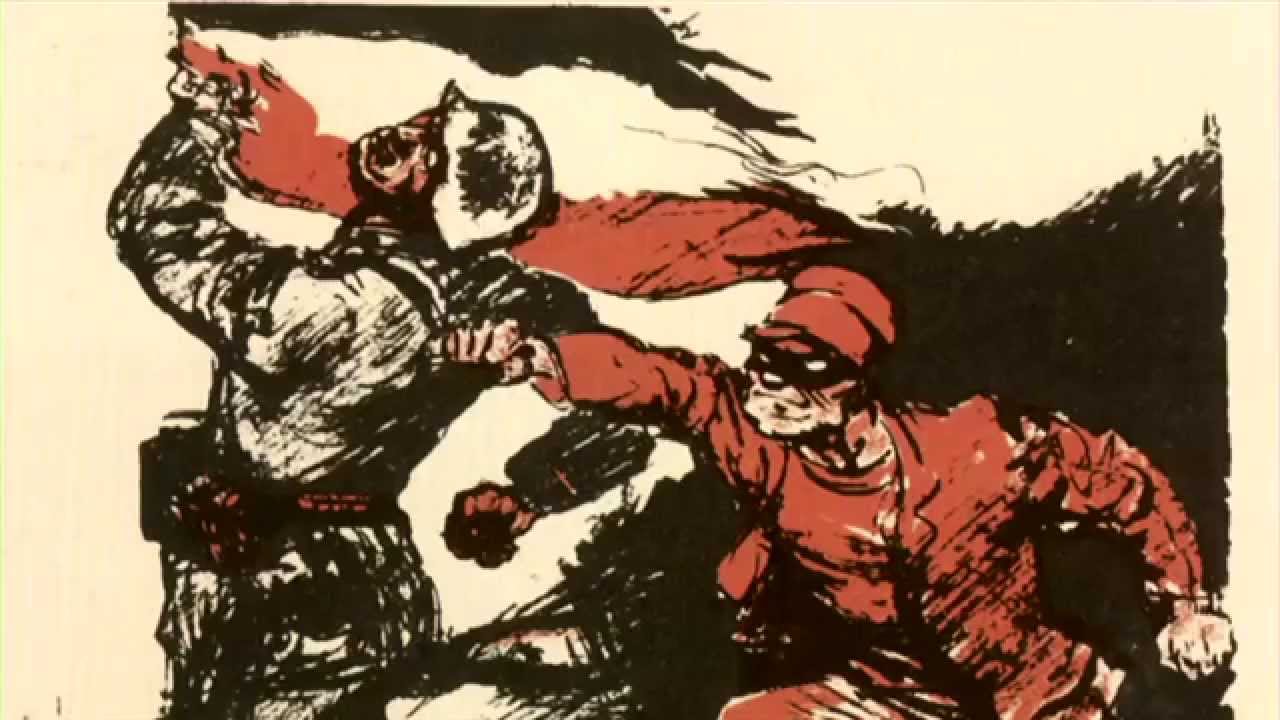

This afternoon of talks organised by the Remembering the Real World War One history group will open up some of the hidden, yet nonetheless crucial, histories which help explain how WW1 ended and how that end is remembered. The talks will be introduced by Mike Levine and are accompanied by an exhibition of contemporary illustrations by the artist, socialist and WW1 veteran Will Dyson which featured in the Daily Herald.

1.45pm: Stabbed in the front and the back – Remembering the end of WW1 in Germany

At last year’s event Roger Ball outlined the massive wave of desertions and refusals amongst German soldiers on the Western Front in 1918 which led to the ‘defeat’ of the Central Powers in his talk How to stop a war: The German servicemen’s revolt of 1918. This year he will first challenge the perception of an ‘allied victory’ in 1918 as merely being the conjunction of US intervention and innovative British military tactics which appears in recent TV programmes. He will try to answer the following nagging questions:

- Why were the final battles of 1918 so decisive and what made them different to the static blood baths of 1916-17?

- Why after more than three years of trench warfare on the western front did the war end so suddenly?

- What part did mass desertions and surrenders at the front and the strikes and unrest at the rear play in this ‘end’?

- Why did allied forces never actually invade Germany?

- Who got rid of the Kaiser?

He will also consider how this supposed German ‘defeat’ was (mis)remembered in the post-war period through the ‘stab in the back myth’ and how that myth has been replicated by nationalists to obscure subversion within armed forces in other historical periods.

3.00pm: Reds in the Ranks – Rebellion and Revolution 1919-1920

It’s no surprise that the WW1+100 anniversaries don’t commemorate the hundreds of thousands of mutineers who challenged their generals and the British government. By way of a morsel of redress, Julian Putkowski will draw attention to the Reds in the ranks of the British Army, and assess the political significance their unprecedented acts of defiance.

Conservative, military and diplomatic historians tend to dismiss the dissent as mass grumbling, a ripple of discontent about demobilisation. However, mutiny was personally a seriously risky business, and the government was worried about Reds in the ranks in the UK undermining British support for anti-Bolshevik forces in Russia. Elsewhere, in India and Egypt, where war-related civil disorder erupted, British troops refused to undertake counterinsurgency operations.

More generally, during a post-war era in which political and diplomatic alliances were transformed, the victorious allies could no longer depend on deferential and disciplined military formations to enforce control over their colonies and recently conquered territories. In those important respects, no less than diplomats who drafted the Versailles Peace Treaty, army mutineers influenced how, when and where the First World War ended.

Event details

Date: , 2018

Time: to

Venue: M Shed, BS1 4RN

Price: Free

With: Mike Levine, Julian Putkowski, Roger Ball

Series: Remembering the Real WWI

The play “Forgotten” currently on at the Arcola Theatre in London tells us something else that historians fail to remember about the Great War.. It is the major contribution by Chinese workers who supported British troops in the work they did by digging trenches, handling supplies, clearing fields of unexploded munitions, removing dead bodies, thereby freeing soldiers of these task so they could fight in the battles.

“Forgotten 遗忘 is inspired by the little-known story of the 140,000 Chinese Labour Corps who left everything and travelled half way around the world to work for Britain and the Allies behind the front lines during World War One.”.